‘Flint Town’ Chronicles Life in a Collapsed City

Alci Rengifo

There are corners of the country where the American dream has decayed into urban poverty, aimlessness and an inevitable rise in crime. Netflix’s visceral new documentary series “Flint Town,” chronicles the trials and tribulations of modern day Flint, Michigan through the experience of its vastly depleted police force. The key question it raises is how far should the boot of the law be applied when social alternatives are gone and if brute force even works at all. This is also a unique documentary of varying nuances. On the surface it appears to be about the police, but what it’s really about is class in America.

Flint is a hollowed out shell when the documentary begins in late 2015, its industries gone and government coffers nearly empty. The second poorest city in America, Flint can barely afford to have police. As the series begins the local force has 98 cops to oversee 100,000 citizens. The city makes national headlines when it is revealed that state bungling has led to lead poisoning of the local water supply. Race relations are also tense as the Black Lives Matter movement becomes prominent in the wake of a focus on police brutality. Amidst all this the documentary follows several local and key figures in the community. Robert Frost is a longtime police officer who tries to maintain a conservative stance regarding his job, his girlfriend is fellow officer Bridgette Balasko, who hopes to one day finally make it into the detective unit. A new mayor, Karen Weaver, is soon elected and she immediately fires the police chief and brings in tough-talking crime fighter Tim Johnson (“I can fight crime in my sleep”) to take over. Johnson essentially militarizes the police, forming a new unit to apply a heavy hand wherever drugs and crime may roam.

“Flint Town” forms part of the ongoing renaissance in documentary filmmaking in which current technology allows for an aesthetic that brings a cinematic power to real life images. Directors Drea Cooper and Zackary Canepari work with photojournalist Jessica Dimmock to capture Flint as an abandoned zone draped in snow, shadow and somberness. Many of the episodes take place at night and the imagery is both raw and haunting as we see the bodies of shooting victims, the empty faces loitering around liquor stores and the stone-faced stares of police officers either zealous in their job, or just jaded from working in a hopeless environment. Even 4th of July fireworks take on an ominous glow in one episode, looking like false pageantry over a landscape of despair.

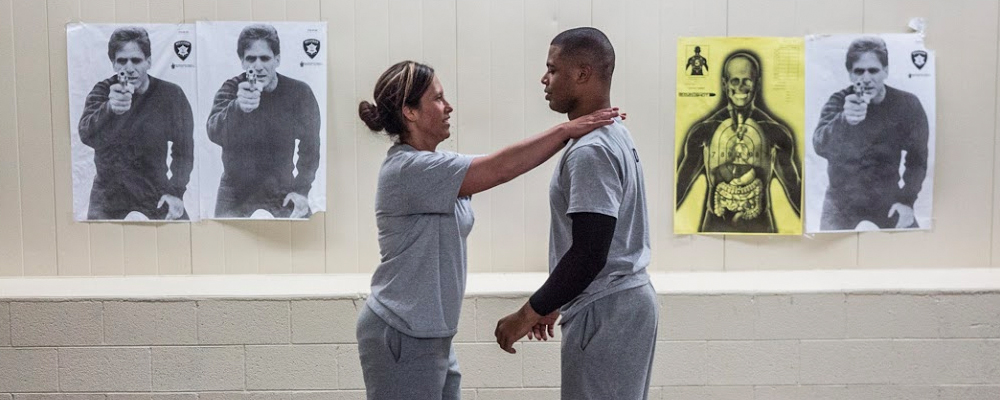

The power of “Flint Town” comes from the way it allows the people it follows to tell their own stories. By hearing their testimonials either before the camera or as they are being followed, we gain an unfiltered insight into their world. In one episode the various members of Johnson’s elite squad display their own, differing views on the issue of police brutality, the white officers are certain only “half the story” is being old, while the black officers articulate the social mistrust that has been around “since slavery.” While Johnson talks tough about turning the fight against crime into a “military operation,” locals at a barbershop very convincingly chat about what’s missing in Flint is more education and culture. These are lives haunted by an economic system that has quickly spiraled out of control without their consent as citizens. There is a moment where Bernie Sanders holds a campaign rally and a local resident delivers a blistering assessment of the situation in Flint, Sanders seems only capable clenching his jaw and nodding. The social subtext of “Flint Town” is of a sector of the populace that feels completely alien to its own government, puzzled over what the role of authority even is in a world where the police can’t afford squad cars and the chance of a decent job is beyond reach. So desperate for officers is the department that one key character, Dion, signs up with his mother to train at the academy.

In the absence of opportunity or solidarity, the system seems only capable of responding with force. As Johnson’s policies come into effect his squad begins roaming Flint in a take no prisoners fashion, targeting loitering, bad driving, drug dealers and shutting down liquor stores that sell illegally to the underage or after hours. But the challenging question the documentary poses is if this is indeed the answer. The police officers are in the same boat as the people they arrest. In one nakedly honest moment Balasko admits she has doubts about the feasibility of raising a family in Flint.

Like Showtime’s “The Trade,” this is a large scale documentary where each chapter moves at an engrossing pace because what it captures is urgent ant full of truth. The faces, moments and experiences are all real. It is a chronicle of a corner of the republic tossed away, but demanding we pay attention.

“Flint Town” premieres March 2 on Netflix.