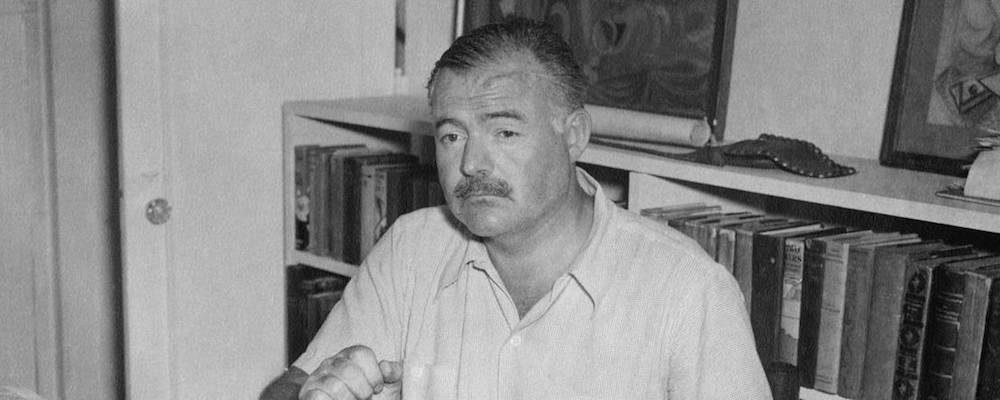

‘Hemingway’: PBS Series Highlights the Contradictions Behind the Myths of an American Literary Icon

Tony Sokol

“There were so many sides to him, he defied geometry,” Ernest Hemingway’s first wife is quoted as saying in the first episode of “Hemingway.” The three-part PBS documentary works as a protractor, calculating angles of the artist’s life with less-explored factors. The documentary opens with a slow camera pan over the pages of the iconic author’s handwritten manuscripts before giving way to footage of a bullfight, in slow motion, over remarks by writer Michael Katakis, who manages the Hemingway estate.

The images are complimentary, defining the iconography of one of the most mythologized writers in American history. The subject is contradictory: Hemingway is presented as a misogynist with an “androgynous” mind-set. His works celebrated toxic masculinity even as he deconstructed its allure. He glorified war, hunting, and bull-fighting, and yet remained a hopeless romantic. He wanted to be a good father and husband, but could be violent and cruel. Hemingway called his father a coward for committing suicide. But 33 years later, the literary legend took his own life, in 1961. He was 61. The documentary makes it clear: while the death was shocking, it came as no surprise to those who knew Hemingway.

Hemingway had been wounded in war, survived car crashes and other perils, but he was terrified of speaking on television. The documentary includes a 1954 interview Hemingway gave NBC. Because he was recuperating from a cerebral injury, the writer insisted he should be able to prepare, getting the questions in advance and reading his answers from cue cards. The archival footage shows Hemingway reading his answers, not only word for word, but comma for comma. His line reads included the punctuation.

The film works as a critique of the writer as well as his chronological biography. Jeff Daniels portrays Hemingway in a warm and vulnerable voice-over, possibly as far from the writer and the macho myth he captured in his stories. Geoffrey C. Ward’s screenplay is loquacious, where Hemingway’s writing was sparse. Hemingway employed simple sentence structures which would amplify the emotion. The documentary points out how he learned this as a cub reporter at the “Kansas City Star,” whose style guide included such edicts as “Use short sentences,” “Use short first paragraphs,” and “Use vigorous English.”

The documentary includes in-depth analysis from literary scholars and fellow writers like Tobias Wolff, Peruvian author Mario Vargas Llosa, and Cuban novelist Leonardo Padura Fuentes. Some of the authors apologize for Hemingway, positing misogynistic stories like “Hills Like White Elephants” don’t show a man who hates women, but is curious about them. They bluntly talk about the anti-Semitism in “The Sun Also Rises,” Hemingway’s first novel, published in 1926. The experts are mixed on whether the author spoke for himself or was trying to capture the culture around him. Irish novelist Edna O’Brien appreciates the female perspective found in the raw prose of “Up in Michigan,” a controversial story which ends with a date rape, but says “The Old Man and the Sea” is “schoolboy writing.” Even the most devoted literary fans chuckle on camera at Papa’s sex scenes.

“Hemingway” was co-directed by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick. With films like “Baseball,” “The Vietnam War,” and “The Civil War” on his resume, Burns is known for making definitive documentaries of his subjects. The Brooklyn-born filmmaker is a stickler for details. From his documentations of the architectural wonders covered in “Brooklyn Bridge” and “The Statue of Liberty,” to his exhaustive human subjects, like Thomas Jefferson, Jackie Robinson, Mark Twain, Frank Lloyd Wright, or the Central Park Five, he leaves little uncovered.

“Hemingway” is divided into three chapters. “A Writer” chronicles the first 30 years of Hemingway’s life, including his childhood in Oak Park, teen years, and his early attempts at writing. It explores how he pushed against standard form and content. “The Avatar” covers the years Hemingway spent in Key West, Florida, with his second wife Pauline. This is when he took care of his young children and took charge of his own mythology, which he directed from the bough of his fishing boat. “The Blank Page” documents his final years. These take on his private battle with depression and alcohol, and his public assertion he was being treated at the Mayo Clinic for high blood pressure rather than his demons.

Keri Russell voices Hemingway’s first wife, Hadley Richardson. Patricia Clarkson takes on the voice role of Pauline Pfeiffer. Meryl Streep speaks the role of Hemingway’s third wife, war correspondent Martha Gellhorn. Mary-Louise Parker voices Mary Welsh. The voice talent is familiar, but the actors melt seamlessly into the characterizations. The documentary is narrated by Peter Coyote, a regular voice in Burns’ films. The documentary includes interviews with Hemingway biographer Mary Dearborn, and the late Sen. John McCain, who says one of his greatest inspirations was Robert Jordan, the main character of “For Whom the Bell Tolls.” They also speak with Hemingway’s son Patrick, now in his early 90s.

The documentary series includes a wealth of small but interesting details. We learn Hemingway wrote 47 versions of “A Farewell to Arms” before he liked the ending; was inspired by Paul Cézanne; and emulated the rhythmic repetitions of Bach. It is especially revelatory to learn how, in early childhood, Hemingway’s mother would dress him and his sister identically as boys or as girls, in what she called “twinning.” The experts discuss Hemingway’s connection to war and death. The documentary is made for Hemingway devotees, who have read his works, and for people who see Hemingway as a pop culture figure who punched people in the mouth.

“He made the mistake that all myth-makers do,” Katakis says early in the documentary series. “He thought that he could control it, and there comes a time that you can’t anymore. It’s taken on a life of its own. It became very exhausting to be Hemingway.” The literary icon wrote novels, nonfiction and short stories, and dispatches from the frontlines of World War II. He dominated American arts for over a generation. The cinema loved his works. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, and the Pulitzer Prize. His books are required reading in schools across the country. Hemingway “remade American literature,” the documentary notes. In Paul Mazursky’s 1984 film “Moscow on the Hudson,” Robin Williams’ Russian circus clown helps his friend practice English for an upcoming visit to the United States. “Do you read Ernest Hemingway,” he asks, invoking the spirit of Americana itself as an international cliché. “Every fucking day,” he is told. It is a comic truism which is universally translatable.

“Hemingway” goes beyond the conventional biographical narrative to link the life to the work. It offers a deft and satisfying coverage of a complex artist and man. Its highlights are how his life influenced his works. He wore his wounds, both from love and from battle, on his novel’s sleeves. The documentary succeeds in its overriding message. If you really want to know Ernest Hemingway, go read his books.

“Hemingway” premieres April 5 with new episodes airing at 8 p.m. ET until April 7 on PBS.