‘Dolores’ Documentary Carries a Timely Message About the Power of Activism

Sandra Miska

With the “intersectionality” one hears often these days among those interested in social justice, the story of Dolores Huerta, a Mexican-American labor leader and civil rights activist, is one that is sure to resonate with many. The documentary “Dolores” explores the life and career of Huerta, who devoted 40 years to the United Farm Workers before founding her own foundation. In this compelling film, we hear not only from those closest to Huerta, including her own children, but the woman herself who is still going strong at age 87.

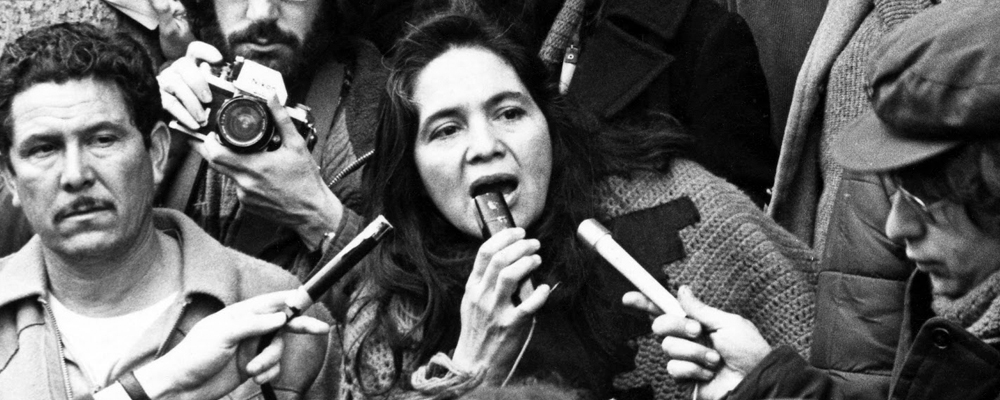

Born in 1930 in New Mexico, Huerta, then a young mother, officially became an activist in 1955 during a time when women were expected to stay confined to the domestic sphere, rejecting a traditional role by devoting a huge chunk of her time to writing proposed legislation which would lead to economic improvements for Latinos. While Cesar Chavez, the activist with whom she founded the United Farm Workers in 1962, is a household name, that of Dolores Huerta is less familiar. Long an adversary of conservative politicians, her role as a leader of the Delano grape boycott didn’t do much to endear her to the likes of Ronald Reagan and George Bush. She courted controversy as recently as 2006 when she declared, “Republicans hate Latinos.” Clips spread of white male TV news anchors shaking their heads and saying that they have never heard of Huerta, with one man even incorrectly labeling her as Cesar Chavez’s girlfriend. Filmmaker Peter Bratt explores how sexism has played a role in Huerta’s life and career and is mostly to blame for why she hasn’t received the same adulation as Chavez. Perhaps one of the most surprising things revealed about Huerta is that she herself was slow to embrace feminism, which actually isn’t too startling when we consider that the early feminist movement was considered to mainly cater to white women, something that Gloria Steinem herself discusses. It can be argued that Huerta and others like her helped shape the feminism movement that we know today, although many may argue that it still may have a ways to go when it comes to inclusiveness.

Huerta is a mother of 11, something that helped motivate her in her activism, while at the same time fueling her detractors, as she had them with three different men, the last one being Richard Chavez, Cesar’s brother, whom she never married but lived happily with for many years. Some of the most emotional moments involve interviews with her (now adult) children, who discuss at length their admiration for their mother, but also reveal how deeply it affected them when her work took her away from them, sometimes for months at a time. Huerta herself discusses the emotional toll all of this took on her. Despite all the heartache, the general feeling is that motherhood played a major role in shaping Huerta’s views. In one archived interview she proudly states how she is helping the world by raising her children to be good, caring, socially conscious people.

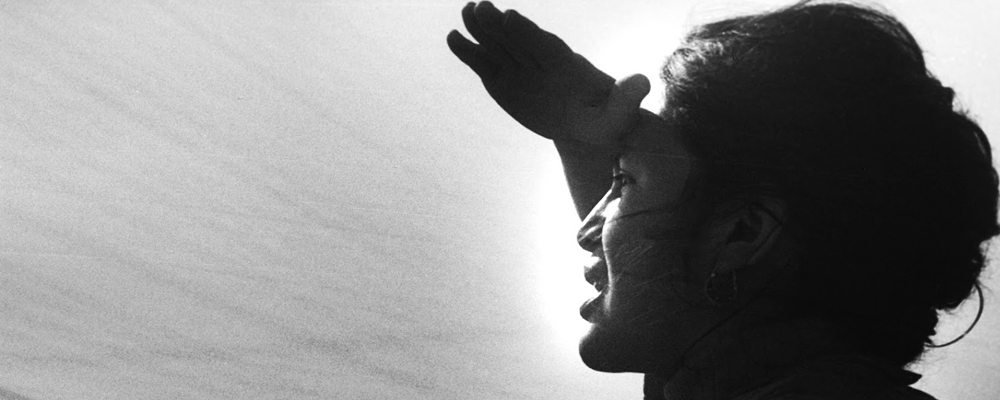

Other powerful moments in “Dolores” that are sure to stay etched in the viewer’s brain include Huerta standing beside her friend and supporter Robert F. Kennedy at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles in 1968 following his primary victory, and there again afterwards when he is gunned down, among the horrified and agonized witnesses. Huerta herself was a victim of violence when she was injured at a protest outside of a fundraiser for then-Vice President George Bush in 1988, another horrifying event that we see through archived footage. However, the documentary ends on an uplifting note, with Huerta chanting, “Si se puede!” – “Yes we can,” a slogan that a certain former president used for his 2008 bid and credits Huerta with. Indeed, those who watch “Dolores” are sure to take with them a piece of Huerta’s can-do, activist spirit.

“Dolores” opens Sept. 1 in New York, Sept. 8 in Los Angeles