Edvard Munch’s Dark Journey ‘Between the Clock and the Bed’ Is at The Met Breuer

John Martin Tilley

Edvard Munch did not have it easy. That much is clear enough in the Met Breuer’s new retrospective of the artist, “Edvard Munch: Between the Clock and the Bed,” on view until Feb. 4.

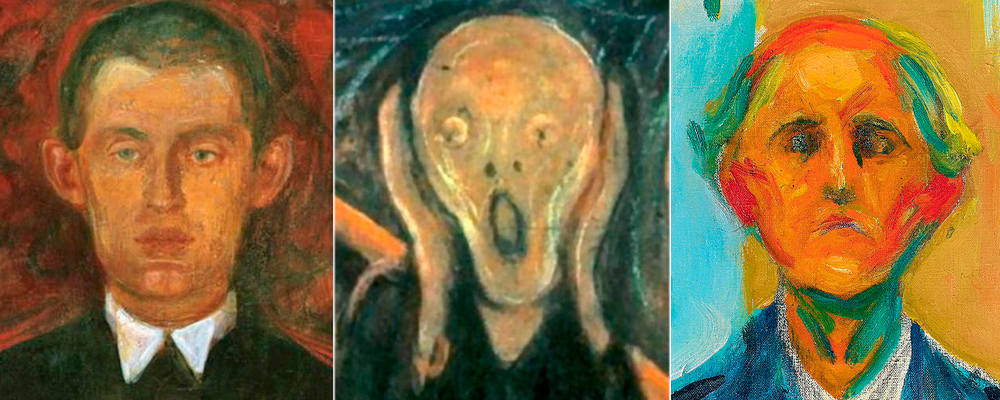

Born and raised in Norway, Munch’s mother died when he was 4, and his sister when he was 14 and she only 15. This might help in small part to explain many of the haunting motifs in his artwork around which this show is organized, the pieces spanning the length of Munch’s long and prolific career. For a self-taught artist, he became incredibly successful in his own time, upsetting the art establishment more than once and thus gaining avant-garde street cred along the way. His pieces are immediately identifiable: his undulating, almost rhythmic use of paint swirls around the figures and landscapes in vibrant, dizzying ripples.

We all know “The Scream.” The museum is wise to include a version of the six painted and besides the inevitable crowd-gathering around this piece, the exhibition itself actually feels like an addition to comment on the the radiating waves of anxiety, fear, disgust, and self-destruction that resound from the iconically distorted figure.

Munch was not afraid of diving into the dark recesses of his mind, his identity, or his relationships and it shows in his tensely psychological self portraits, “self scrutinies,” he aptly called them. There is a naked honesty in his depiction of himself and his struggles that is surely worth more exploration than I have room for here; in a way it feels almost documentarian to turn his artistic eye upon his own sometimes deplorable habits, the allusions to alcoholism are particularly fraught. “Self Portrait in Hell” is so personal and cataclysmic it defies comparison; it is an invasion and a revelation simultaneously, signatures of Munch’s singular visual magnitude.

Munch’s works are self-consciously intense, and they make for an incredible show when seen in tandem as arranged here. The section “Nocturnes” is particularly lovely, the toying with light and shadow on landscapes and water a timeless delight that provides a moment of respite in an otherwise turbulent body of work. It could still be argued, nonetheless, that the night scenes are just as full-to-the-brim with roiling spiritual darkness as the others, but at least from an aesthetic viewpoint they feel like little jewels of peace for Munch.

The human figures are another story entirely. Sometimes they hunch in despair, turning away from the viewer, sometimes they meet the viewer’s eye with unexpected abruptness, and sometimes they warp into masks of themselves, their faces like nightmarish cartoons. They’re gaunt and pale, their eyes sunken and hallow, sometimes to the point of striking in the viewer a nervousness, a jumpiness, dare I say even fear? Imagine some of these at the end of a dark hallway and they start to seem less like studies in Symbolism and Expressionism and more like studies in straight-up horror.

His style informs the subject in perfect, eerie unison. This paint feels like it has been almost violently applied at times – indeed, in a moment of particular experimentation in “The Sick Child,” he actually scraped away parts of dried paint to… what? simply to create texture? to dig into the figures to reveal not only layered pigments but layers of their identity? or perhaps even to attack them? Munch has such a hostile artistic eye at times, the canvases undoubtedly quiver with his emotional release upon them, the paint a weapon and a compass into the realms of his and his figures’ tormented spiritual existences. It makes for a marvelous and frightening journey, to say the very least.

“Edvard Munch: Between the Clock and the Bed“ is at The Met Breuer Nov. 15, 2017 through Feb. 4, 2018.