Ethan Hawke Burns With Radical Awakening in ‘First Reformed’

Alci Rengifo

A solemn and contemplating man awakens to a radical consciousness in “First Reformed.” This rare, elegant and challenging drama is a work of serene force. It marks a return to form for writer/director Paul Schrader, one of the great American filmmakers of the last 40 years. Schrader made his mark by writing some of Martin Scorsese’s best films, in particular “Taxi Driver” and “Raging Bull.” As a director Schrader’s own movies have been passionate explorations of personalities, guilt, explosive feelings and raging talents. In “First Reformed” he tackles a variety of visceral themes, challenging the audience to ponder both issues of faith and the condition of the modern world.

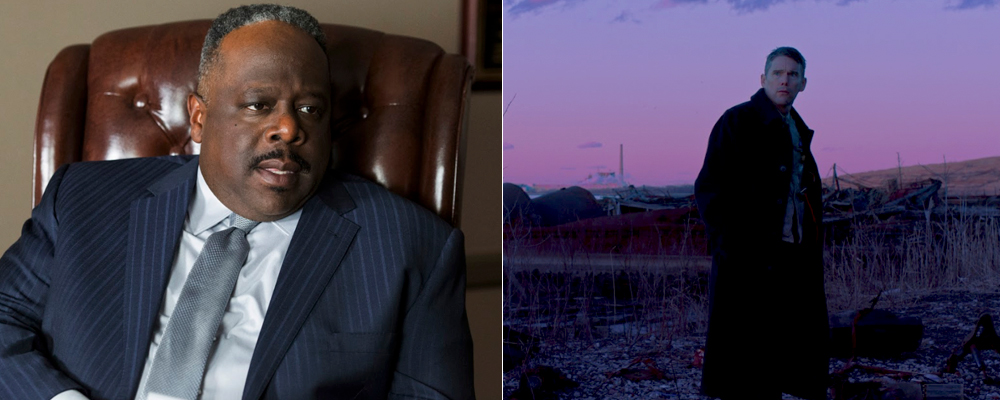

Ethan Hawke plays the Reverend Toller, who is in charge of a small, colonial-era Protestant church in New York State. A former military chaplain, Toller lost his wife after their son was killed fighting in Iraq. He spends his days and nights cloistered, drinking and feeling physical signs of illness. He refuses the loving advances of a church worker named Esther (Victoria Hill). Toller has decided to write a journal for twelve months, documenting his inner most feelings and observations. But the outside world intrudes when a young married couple, Mary (Amanda Seyfried) and Michael (Philip Ettinger), come to Toller seeking counsel. Michael is a radical environmental activist plagued by depression. Mary is pregnant and Michael wonders if it’s even worth bringing a life into a world so ruined and headed for cataclysm. His talks with Toller challenge the reverend’s subdued nature, provoking a sudden, profound awareness both political and personal. Tragedy soon strikes, driving Toller into a deeper clash between the cosmetic attitudes of his church and an overwhelming sense of urgency and bleakness. The pastor of the megachurch overseeing Toller’s small church, Rev. Cedric Kyles (Cedric the Entertainer), notices not all is well with Toller and hopes he can be in shape for the church’s upcoming 200th anniversary. But Toller is slowly becoming driven towards a higher calling against what he perceives are the real forces of darkness poisoning “God’s creation.”

“First Reformed” features the kind of intellectually and dramatically challenging filmmaking you don’t see much of in mainstream cinema. Schrader has crafted a story of personal force reminiscent of the films of Ingmar Bergman in its stark view of human nature and its poetic eye for the private torments of individuals. Himself the product of a strict Calvinist home, Schrader found freedom in the art of cinema as a young critic turned screenwriter. His movies all bare the mark of an artist contemplating the beliefs and inner struggles of human beings. In his 1985 masterpiece “Mishima,” he dramatized the life of a Japanese author who lived by a radically devout code of tradition, in “American Gigolo” Richard Gere plays a man who lives by selling his body but is soon thrown into a serious moral crisis involving murder. With “First Reformed” Schrader presents a man in his own corner of the world, processing his own struggles, who begins to fill a void with a sudden consciousness for the decay of the earth. The screenplay is a beautifully layered work of art, as it gracefully flows from theme to theme. Toller’s preacher is not a character who only speaks to those of religious faith in the audience. The issues he begins to learn about and absorb are being contemplated by people from all walks of life. Schrader presents an allegory of a society feeling increasing unease, whether over the environment, politics, war or all three. Toller sits in front of his computer, reading the statistics of climate change, learning that a major polluter is a donor to his parent mega church, and it all clicks. In another scene a corporate suit chastises him in a diner over sympathizing with Michael, using the logic of how could Toller possibly know what God would want for the earth?

The other key layer of this film is how it explores the dueling identities within modern American Protestantism. Because Schrader understands this world so well he is able to present clearly the clash of ideas taking place within an institution struggling between conservatism and progressive ideas, commerce and genuine theology. Toller makes the logical case that if God made the world, why would such a creator want humans to destroy it? Cedric argues that the Lord did indeed flood the whole thing once, for forty days and forty nights. And besides, they can’t afford to get political, at least in a left-wing sense. In another strong scene Toller sits in on a church youth group with a very self-help, TedTalk meets Jesus vibe. But when a student asks a hard question Toller offers a very unsafe answer, prompting a conservative in the group to bark his own complaint. Yet soon enough Toller himself will morph into a more radical being, finding a suicide bomb vest Michael has fashioned, and wondering if sometimes you just can’t turn the other cheek.

“First Reformed” is the farthest thing you can find from a “commercial movie.” But because Schrader could care less about catering to a specific demographic for big box office, he is free to offer something unique and provocative. This is the kind of movie you can debate or discuss afterwards. It is a work of multiple views and depths, never taking one extreme side over another. The ending seems to say, in a scene both beautiful and fierce, that beyond religion and ideology, what can truly save us is love in the truest sense of one individual wanting another. Schrader’s visual style is contemplative but meticulously well-composed, focusing on the framing of faces and profiles.

For Ethan Hawke this film is a triumph. His performance is both raw and focused, full of goodness and despair. He plays Toller as an open, questioning man operating within a specific belief system. He is never posturing (like the Cedric character), because since he takes his faith seriously, the despairing questions Michael brings him shake him at his core. Amanda Seyfried as Mary also disappears in her role. Schrader never cheapens their relationship with clichés. They are written and acted as individuals enduring together.

“First Reformed” stands out as a film that revives the kind of transcendental cinema that was such a part of the independent film tradition, before the current wave of hyper commercial filmmaking. Schrader is reminding us with this film that we should take the time to also contemplate challenging themes in a movie. By all means enjoy the rowdy fun of “Deadpool 2,” but after a dose of escapism, there might still be room for cinema that can’t quite be put into a meme. “First Reformed” may seem at first like it is about one man, in one specific institution, but it is very much about the wider world as it is and feels today. This is one of the year’s best films.

“First Reformed” opens May 18 in select theaters.