HBO’s ‘The Tale’ Journeys Into a Woman’s Painful Memories of Past Abuse

Alci Rengifo

HBO’s “The Tale” is a brave work of drama as testimonial. A woman journeys into the deepest recesses of her memory, questioning events as she envisions them, before arriving at shattering personal reflections. Director Jennifer Fox stands here more open than few filmmakers ever dare to go, because this story of sexual abuse is her own. So determined and urgent is Fox in sharing these events that she has not even changed her name in the script. This is a film that tackles a particularly delicate topic with a special complexity. Because the filmmaker actually lived what transpires on screen, the psychological conflict and emotional struggles become more wrenching, more harrowing than if this story were told by an outsider.

Documentary filmmaker and professor, Jennifer Fox (Laura Dern) is contacted by her mother Nettie (Ellen Burstyn), who has found an old short story Jennifer wrote as a young girl. It describes her relationship with an older man, when she was 13. The writings were jotted down during her days as a horse riding student under the tutelage of Mrs. G (Elizabeth Debicki) and running coach Bill (Jason Ritter). Jennifer begins to trace back her moments at the horse riding ranch, stepping into her memories and seeing herself through her written story. Suddenly what seemed so clear as a recollection becomes ominous. Highly intelligent and thus rebellious at such a young age, Jennifer (Isabelle Nélisse) is drawn to the independent spirit of Mrs. G and the openness of Bill, who is really, calculatingly seducing her and manipulating her young, curious emotions. Soon enough Bill begins pushing the relationship into sexual intercourse. For years Jennifer has grappled with the trauma of the encounter by restructuring her memories, convincing herself of a narrative in which this was her first love. But now older and confronting the real implications of what happened, she must face the darker, scarring truth.

The power of “The Tale” resides in its exploration of the very nature of memory. Many of us will deal with traumatic events or hurtful moments, buried and insistent in our minds, by altering the recollection. Early in the film Jennifer first remembers herself as older when she first meets Mrs. G and Bill, but then her mother shows her a picture of what she actually looked like at the time and it is a shattering of illusion. She was so young at 13, and so small. When she finds Mrs. G, now as an elderly woman (Frances Conroy), she is astounded at how short she is, when as a child the riding teacher seemed like a giant. Fox unfolds her film in layers of memory, each layer revealing a starker truth. Instead of resorting to the usual technique of flashbacks, Fox edits the film in a way where the present directly cuts into the past. At times Jennifer will find herself inside a memory, speaking directly to the young Mrs. G or to her 13-year-old self, asking questions and breaking down events. The editing and writing create a dreamlike effect that feels like when we try hard to remember. Jennifer may even return to a memory we have already visited, suddenly remembering someone else previously forgotten. The result is unnerving because the sense of a coming, terrible revelation accumulates. It is a feeling akin to when you are waiting for news or information you know will be hurtful. The more Jennifer reads her story and the more figures from the past she finds, the more she realizes she had been the victim of predatory impulses.

When Fox depicts the sexual encounters between Jennifer and Bill she does so in a way that is astonishingly brave. Films like “The Woodsman” and “Happiness” have dealt openly with the topic of child sex abuse, yet the crime itself always remains distant. Fox refuses to be detached or to look away. She captures the most painful of her memories before the camera and helps us understand just how such individuals like Bill and Mrs. G operate. It is incredibly eerie how Bill takes advantage of Jennifer’s curiosity, manipulating her into certain acts, using certain words to appeal to her naïveté. Like Eli Roth’s “The War Zone,” this is a film that wants the viewer to clearly understand what the sexual abuse of a child entails, what it feels like and what it does psychologically. For some viewers these sections of the film may be hard to handle, they are piercing in their clarity.

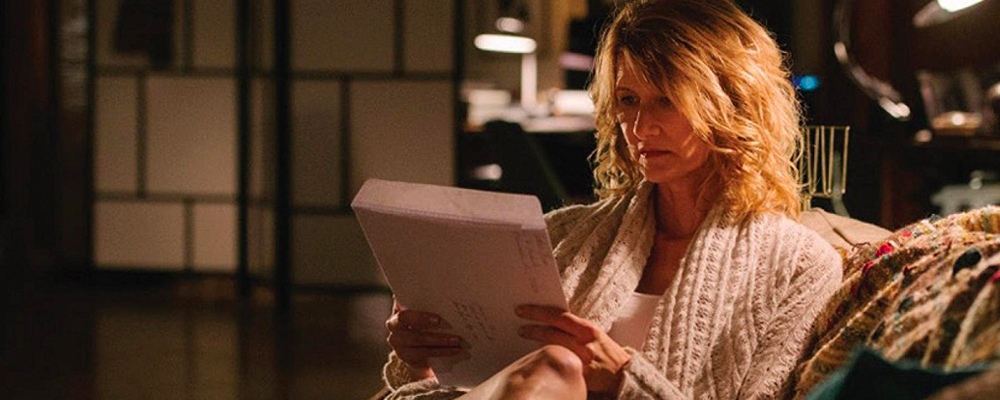

It must have been quite the responsibility for Laura Dern to play the very person directing her, but she delivers here one of her best recent roles. She never plays Jennifer as a “victim,” but as a person slowly coming to terms with a trauma. By the end, when she confronts an older Bill (John Heard), she has come to a new understanding in her life that is heartbreaking because it is a reckoning, and she will never be the same. Elizabeth Debicki and Jason Ritter ooze with a particular unsavoriness that also reveals itself in layers. At first they seem to be libertine sophisticates, but it is all a mask for shamelessness. A small but meaningful role is Jennifer’s boyfriend, Martin, played by rapper-poet Common. When he expresses his concern for Jennifer’s well-being after he learns about what happened to her, a fight ensues that feels very adult in its tension.

“The Tale” is a filmmaker coming to terms with an event in her life, exposing deep and painful memories through drama. The final resolution is appropriately imperfect, because in real life closure is rarely ever simple, or absolute. We live and things happen to us, we then try and rewrite it all in the records of our memories. Fox seems to be saying that memories, like history, should be mined and confronted, or else we only pretend we are doing ok.

“The Tale” airs May 26 at 10 p.m. ET on HBO.