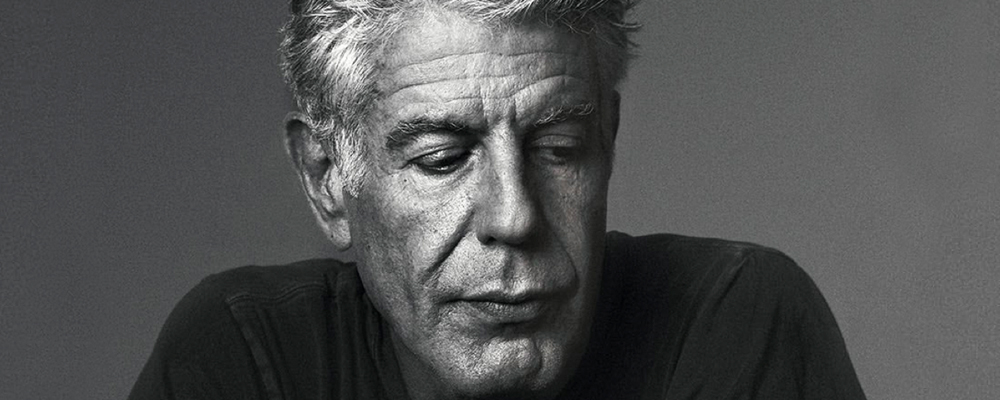

Anthony Bourdain Used His Global Exploration of Food to Break Down Cultural Barriers

Alci Rengifo

Loved by millions for sharing his exploration of the world’s many cultures and cuisines, Anthony Bourdain has begun the ultimate journey. Leaving too soon at age 61, the New York City native died in Strasbourg, France, a man of the world until the end. Food is what the mass audiences immediately associate with his name, because many came to know him via his Travel Channel and CNN docu-series’ “Anthony Bourdain: No Reservations” and “Anthony Bourdain: Parts Unknown.” Part travelogue, part reflection on the condition of the world, the series’ followed Bourdain to big and small corners of the globe, as he tasted the cuisines of continents, while making a genuine contact with the people and their culture. Bourdain understood that culture is much defined by the foods we eat, and that sincere conversation and connections form most easily at the dinner table.

Bourdain was defined by an independent and rebellious spirit formed and shaped by life experiences. Even after finding fame on television, he would criticize famous television chefs for having never worked in a kitchen. For Bourdain it was important to know the world from the bottom up, because this is how an artist truly hones their craft. Of his four tattoos, possibly the most telling is an ouroboros he received in Malaysia. It is the image of a snake forming a circle, its lips touching its tail, as a symbol of continuing rebirth. Bourdain knew the meaning of this image well, since he himself had been reinvented many times by life’s turns. Respected chef of New York restaurants and chronic smoker (until 2007), hard drinker and martial arts enthusiast, recovering drug user and champion of the underdog, he was all this and more.

Like Hunter S. Thompson or Lord Byron, Bourdain was a rebel poet who could wield the pen as well as cook a ferocious stew. His Travel Channel show “No Reservations” featured disclaimers for the audience about the language and content, since Bourdain used his exploration of cooking to bluntly discuss life and its raw truths. His sarcasm was elegant, but with the sharpness of a kitchen knife. Bourdain defined the cultured rebel at a time when hipster culture threatens to devour all facets of culture itself. His books, such as “Kitchen Confidential” and “Medium Raw: A Bloody Valentine to the World of Food and the People Who Cook,” explore the world of dining and restaurants with a respect for good food while making keen cultural critiques. In 1985 he married his high school sweetheart, Nancy Putkoski, divorcing after 20 years. In “Medium Raw,” Bordain wrote that he felt suicidal afterwards, wandering the Caribbean in a profound depression. This is a man who felt deeply. In 2007 he married Ottavia Busia, a mixed martial artist with whom he had a daughter, yet his devotion to his emerging TV career led to the marriage ending. By the time of his death, Bourdain was involved with Italian filmmaker Asia Argento, who recently made headlines by delivering a blistering speech at the Cannes film festival, condemning Harvey Weinstein and warning that other abusers would soon meet his fate. Maybe it was inevitable that Bourdain would find solace with an artist with such a passionate heart, who felt a moment as deeply as him.

A passion for knowing the world is what fueled Bourdain’s final manifestation as the host of “Parts Unknown.” Bourdain had little interest in merely promoting the expensive or official, “national” menus. In his famous episode with guest Barack Obama, Bourdain and the president sit down to have Bun Cha in a small, family-run spot in a working class part of Hanoi. The two men share beers among the local people, not surrounded by powerful dignitaries. He promoted the value of recognizing “peasant” foods from other cultures, including meals with animal parts 21st century westerners would scoff at munching. Bourdain would dine on raw seal eyeball, bird embryos and even maggots. Yes, there are corners of the world where such delicacies have been eaten for centuries, and Bourdain wanted you to know this. But he never covered such cuisines with sensationalism or a condescending tone. He genuinely wanted viewers to learn and appreciate how the wider world lives. Bourdain had a way of pulling truly confessional statements from his more famous guests. In one episode punk rock godfather Iggy Pop confesses to Bourdain that being loved gives him the most joy. You can see Iggy almost blushing as he eats a delectable shrimp. Fearless and compassionate, Bourdain would not hesitate to cross borders. He championed the immigrant Latin American workers toiling in U.S. kitchens, and in one controversial episode of “Parts Unknown” he dines with Israelis in the West Bank and Palestinians in Gaza. “People are not statistics,” is how Bourdain responded to heated audience responses to the episode.

Good television, like good cinema and literature, has the potential of placing us in the shoes of others. For Bourdain food had this same power, and coupled with the medium of television, it could enlighten the viewer and create a special awareness. Having lived a life of many roads, heartbreak and success, Bourdain used his gifts to help others experience and travel with him. Even if you couldn’t make your way to Lebanon or France, Bourdain suggested that by cooking another culture’s cuisine at home, you could indeed travel there. In a world of growing divisions, fierce and dark passions, Bourdain was a human voice amid the noise now overwhelming us. Only he could know what was happening in his most private self and why he made his final decision. But he will be missed, because he understood that the most radical act can sometimes be the simple embrace of someone else regardless of where they come from.

Anthony Bourdain died on June 8, 2018 in Kaysersberg, France.