Nas Takes on Society With Kanye West-Produced ‘Nasir’

Adi Mehta

For the fourth of his slapdash five-in-five-weeks record release spree, Kanye West has joined forces with none other than the legendary Nas. Hip-hop purists worldwide have been pacing nervously about the prospects of this seemingly unholy alliance. Nas has awed since his era-defining 1994 debut, “Illmatic,” but has hardly been consistent. He once titled an album “Hip Hop Is Dead,” and his absence since 2012 has caused some to consider him literally. It will relieve many that the new album, “Nasir,” finds West turning out seven songs that seem to have been produced with Nas’ signature style in mind. At 26 minutes, it’s not exactly a fully realized album, but it’s classic Nas with some Kanye quirk.

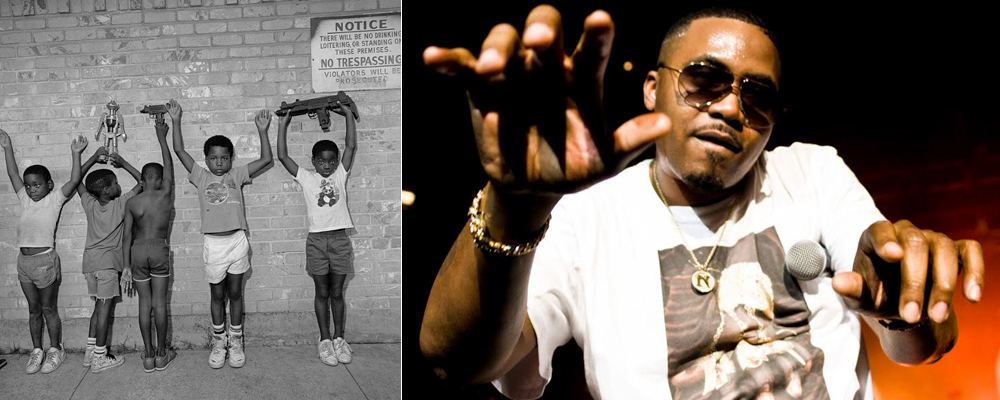

“Not For Radio” begins with epic orchestral sounds over a no-frills beat. The pomp is well-suited for Nas, whose wise street poet posturing, combined with the presumed hip-hop bravado, warrants a cinematic entry. Nas begins in full Afrocentric mode, summoning, “Black Kemet gods,” and going on to dabble in revisionist history. Among the claims he makes are that Lincoln didn’t end slavery, that SWAT was created to stop the Black Panthers, and that both Edgar Hoover and the founder of FOX News were black. Maybe. At any rate, it sets the stage for the serious social commentary that follows. The chorus line, “I think they scared of us,” reiterates Public Enemy’s “Fear Of a Black Planet,” an idea apparently still relevant today. The destitution of inner city youth is a prominent theme, captured effectively in the cover art, taken by photojournalist Mary Ellen Mark as part of a 1988 feature titled “The War Zone.” The original caption described that “criminals dominate the area,” and that “kids learn to play by watching the police.” Today, the latter detail is especially troubling.

“Cops” is built around a sample from Slick Rick’s “Children Story” in which Rick narrates,“The cops shot the kid.” The line is clipped, and looped unremittingly for the whole track. The grating monotony might be a bit much, but it’s likely by design. If you find yourself asking why you are being told repetitively that “the cops shot the kid,” you need only consider recent headlines. The sound byte functions as a repeated reminder of a repeated occurence. And it’s to this beat that Nas takes the mic. He protests, “White kids are brought in alive / Black kids get hit with like five,” and manages to drop historical references and contemporary social commentary in little, loaded bars, for example, “Reminds me of Emmett Till / Let’s remind ’em why Kap kneels.” On the chorus, chords enter, and the sample is repitched into melodic segments. The absurdity of creating a tune from the mechanical splicing of such an unsettling snippet hints at the greater absurdity of living in these times, and trying to come to grips with them.

On “White Label,” West constructs a musical conveyance from a sliced sample. It’s more of a pulse than a beat, as the drums are nearly filtered out. The moments when they drop out completely, leaving Nas’ flow suspended, create a compelling dynamic. Repeated utterances of “I’m gonna” finally flesh out, at the end of a measure, into “I’m gonna have to leave you.” The sentiment seems to be about not allowing one’s self to be held back. Nas pats himself on the back for coming so far, and proceeds to pencil his name prominently into the titular label. He insists, “I don’t owe you… You are an extension of what I’ve worked hard to build.” Indeed, Nas has had a considerable hand in shaping hip-hop history.

“Bonjour” is a rather lighthearted, cheery number, not exactly Nas’ forte, but it works. The beat could almost be on “Illmatic,” with sparse breaks and sampled piano. Languid, soulful vocals from Tony Williams give a colorful, frivolous feel. Nas raps, “Hit up the south of France after tour, bonjour,” and delivers some typical rap braggadocio about luxurious living and sexual prowess, but is unable to make it through without a couple solemn observations. He notes, “Vacations I didn’t like, put myself through a guilt trip (bonjour) / All these beautiful places, but the cities be poor.” He revisits the theme of unprivileged background, suggesting, “You wealthy when your kid’s upbringing better than yours.”

This segues into “Everything,” which consoles the less fortunate, “Dark boy, don’t you cry.” The atmospheric instrumental gives way to a tight, minimal groove, and West sings lines in the chorus that he likely wrote himself: “If I could change anything… I would change everything.” Nas elaborates, “People do anything to be involved in everything / Inclusion is a hell of a drug.” At one point, he describes a baby getting his first immunization shots, and thinking, “I thought you would protect me from this scary place.” Having risen from the Queensbridge projects, Nas knows no vaccine will lighten the struggle.

“Adam and Eve” begins with “The ghetto Othello, the Moor,” once again hinting at discrimination and hardship. On the chorus, The-Dream sings, “Adam and Eve / Don’t fall too far from the apple tree.” Here, the apple falling near the tree amounts to children finding themselves restricted to the oppressive confines of the underclass. It’s an idea Nas expressed in an older song, “Film,” with the affirmation, “The ghetto is my garden of Eden.” This concern makes its way into the closer, “Simple Things,” which concludes with Nas wishing, “I just want my kids to have the same peace I’m blessed with.” West is at his soul-sampling best here, crafting an unassuming yet intricate, ethereal soundscape with snipped, filtered voices artfully panned and placed. Ironically, Nas brags, on this song, “Never sold a record for the beat, it’s my verses they purchase.” Still, it’s a beat that befits him.

Kanye’s last three releases have all seemed a bit whimsical and arbitrary, and such is also the case with “Nasir.” There seems to be an emphasis on immediacy, at the expense of cohesive crafting. This isn’t necessarily bad; untethered artistic expression has a certain charm, and can be a refreshing change from more stilted undertakings. The drawback is that there’s no song here as awe-inspiring as, say, “One Mic.” Nas’ lyrics seem a little more loosely structured than usual. Still, he’s on top of his rap game, and has plenty of important things to say. The greatest success of this record is, arguably, the chemistry between Nas and Kanye. While Nas’ music has taken different forms over the years, there is a general pattern to his aesthetic, and Kanye seems to have captured it, and channeled it into avenues that strike as simultaneously familiar and fresh.

“Nasir” is available June 15 on Apple Music