‘Kusama: Infinity’ Captures Yayoi Kusama’s Road to Prominence

Alci Rengifo

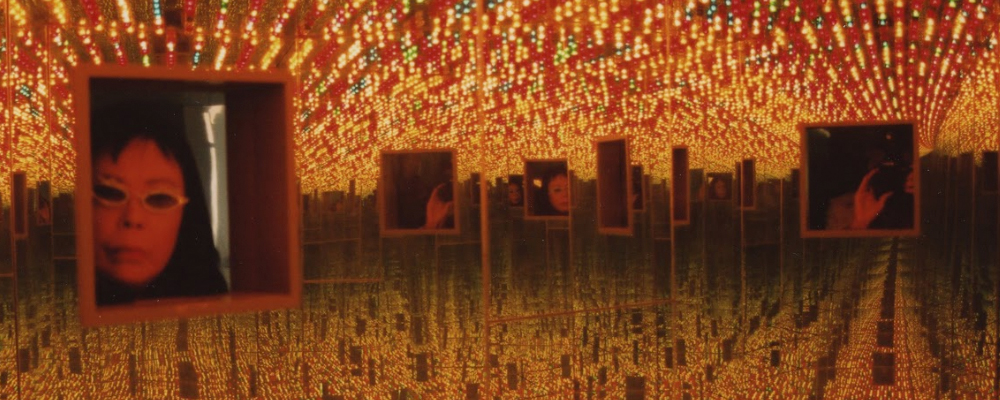

Behind nearly every iconic name we gaze upon in museum halls there are countless untold stories of struggle and heartbreak. “Kusama: Infinity” is a documentary chronicling the life of a magnificent artist, it is also a stirring chronicle of the crushing road to recognition. Today, Yayoi Kusama is the world’s top selling female artist, famous for her “Infinity Rooms,” but she has only achieved this after decades of obscurity, discrimination and battles with depression. Like Van Gogh or Goya, Kusama’s art is powerful because it is culled from an imagination forged by harsh experience.

The documentary traces Kusama’s life from her birth in Matsumoto, Japan. She grows up under the shadow of World War II and a dark family. Her mother was domineering, her father was a serial cheater, and witnessing all this left Kusama with both a sense of alienation and detachment from sexuality. But from a very young age an urge to paint and make art manifested itself in her very being. With little support from her family, she insists on being an artist and begins making paintings alluring and strange. She writes to the American artist Georgia O’Keeffe and is given words of encouragement. Kusama soon makes her way to 1950s New York, eventually meeting major figures like Andy Warhol. But in a world which still favors white men while women artists are ostracized, Kusama struggles to get the respect and attention she deserves. Depression sets in continuously, but she marches ahead, becoming increasingly obsessed with the aesthetics of infinity. She becomes part of the 60s antiwar movement, holding nude happenings that bring her notoriety. But Kusama is too radical for the mainstream and still an outsider within the counterculture movement, so she disappears, returning to Japan until life takes another turn and she is finally discovered by the world.

“Kusama: Infinity” is first of all a fascinating biography. While much of the documentary is narrated by curators, fellow artists and friends, it is Kusama’s own voice that stays in the memory. She speaks with the quiet, observant wisdom of an 89-year-old reflecting on the past, yet still creating. Director Heather Lenz contrasts stock footage of the artist in her younger days, already with a somber look in the eyes and a fierce demeanor, with recent footage of Kusama carefully painting new patterns on vast canvases. It is quite the life this woman has lived, spanning World War II, the upheavals of the 60s and now this postmodern age we are living through in the arts. Many of the anecdotes could be used for individual movies. Kusama shares about meeting the surrealist Joseph Cornell, who became maddeningly infatuated and obsessed with her. He would compose poems and endless streams of love letters, finally winning her over only to have the relationship tarnished by his own, domineering mother. So original was Kusama’s talent that Andy Warhol openly aped it, taking her idea of adorning an entire gallery wall with the same photograph of her piece “One Thousand Boats,” and doing his own variation with pictures of a cow. For years Kusama suffered the typical fate of artists who are instantly recognized by their peers, just not by the wider or world (or the necessary financial backers).

One of the documentary’s important points is that Kusama particularly suffered for being an Asian woman. As white male notables like Jackson Pollock and Warhol found patronage and fame, Kusama was brushed aside. Possibly the most endearing quality of her character is the sheer will to keep going, no matter the tempests thrown at her by the world. She stubbornly insisted on being recognized, becoming a master in everything from painting to collage to sculpture. When the Vietnam War dominated public discourse, she jumped into the fray, holding nude happenings to demonstrate how destroying the human body was horrific. Unlike some of her peers, she had experienced the barbarism of war first hand. There is a stunning moment where we learn that even as a young girl during WWII, she refused to follow Japan’s nationalist march. Kusama emerges as a rare individual with a truly strong and independent mind.

This is also a fine psychological portrait of art as therapy and conduit. Kusama admits witnessing her father’s philandering stunted her own sexual growth. Her artwork is filled with images of bodily distortion and strange, phallic shapes, in particular during the 50s and 60s. Before she was re-introduced in the 1990s, depression was a constant barrier, at one point driving her to jump out a window (landing a bike saved her from certain death). Each phase of Kusama’s life takes shape in her art, from vast images of infinity to joyous, colorful sculptures to dark, gothic collages. Kusama sought fame, but she produces art because she has no choice, in the same way writers like Bukowski or Kafka wrote to exorcise their demons. Now her work graces some of the world’s great museums, but Kusama only achieved this after brutal moments of doubt.

“Kusama: Infinity” is an endlessly fascinating documentary about an inspiring life, but it is also a universal story. It takes a lot of courage to follow one’s own, independent path and to cast away doubts and doubters. This documentary is about Kusama, and about that person out there picking up a brush, instrument or pen, and wondering if it’s even worth a try.

“Kusama: Infinity” opens Sept. 7 in select theaters.