‘The Sisters Brothers’ Turns the Myth of the Old West on Its Head

Michael Amundsen

The opening scene of “The Sisters Brothers” shows an unadorned house standing on barren plains in the darkness. Shadowy figures hide behind nearby rocks introducing themselves as the Sisters Brothers with a promise of mercy if those inside surrender a comrade. Flashes of fire illuminate the black as weapons open fire. And then silence. The shadows move from the rocks towards the house. They enter and execute anyone still alive. There is no light. Faces are in shadow. The lone survivor escapes through a hole in the roof. He doesn’t live long.

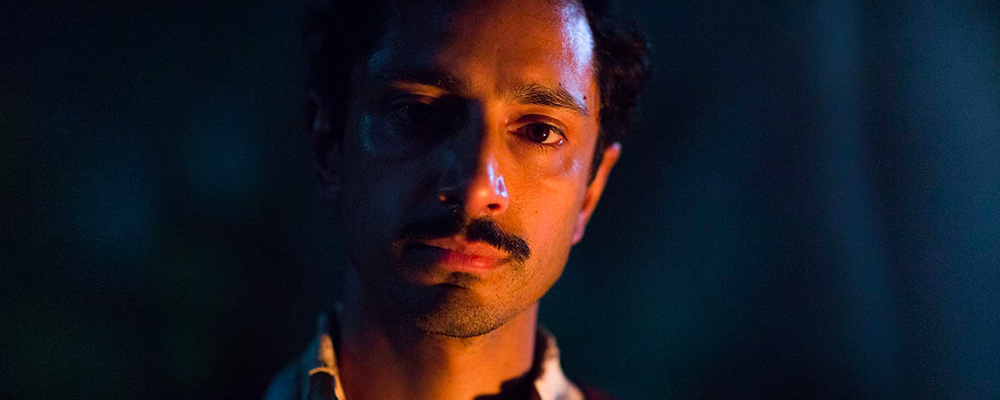

The next scene happens the next day. It may be daytime but the muted sunshine doesn’t make it bright. Charlie Sisters (Joaquin Phoenix) receives payment and their next assignment from the Commodore, a passionless frontier capitalist played by the underused Rutger Hauer. Charlie conveys the assignment to the other Sisters brother Eli (John C. Reilly). A person by the ambitious name of Hermann Kermit Warm (Riz Ahmed) has robbed the Commodore and he must die. They are to meet up with another Commodore employee, John Morris (Jake Gyllenhaal) who will deliver to them the above-mentioned Warm for execution.

But Charlie doesn’t tell Eli the whole truth and it won’t be the first time during the course of the movie that lies and betrayal will change or destroy the lives of Morris, Warm, and the Sisters brothers.

John Ford directed Westerns that were open to the landscape around them. They were as authentic as a Hollywood Western could be, dusty and grim, but often playing second fiddle to the epic landscape around them.

French director Jacques Audiard brings a different sensibility. His film is equally embedded in the western landscape. But the sun is always filtered with muted, desaturated earth tones. And unlike Ford’s monumental nature, Audiard’s borders on perilous claustrophobia, where a spider can crawl into a sleeping man’s mouth with awful results or a bison can gore tethered horses in the night. Audiard’s camera uses equally claustrophobic close-ups for the actors. Instead of intimate, the audience feels distanced from any one of the monochrome shadows that populate this film, including the Sisters brothers themselves.

Like all good Westerns, “The Sisters Brothers” is a story of redemption and change. It is a story that belongs exclusively to the Sisters brothers, while most everyone else exists to die. And in their death, contribute to the change and redemption of Charlie and Eli.

The acting is solid and seems as organic as the nature around them. John C. Reilly underplays to great effect. His simple portrayal is rooted in the soul of a simple man who longs for another life and yet is committed to the protection of the crazier brother. Gyllenhaal does his acting homework. Portraying John Morris as searching lost soul, he captures the essence and accent of a gentle educated New Englander of 1851. Ahmed provides the glow of an earnest believer in the best in humankind, regardless of the inhumanity that surrounds him.

Phoenix makes the character of Charlie strongly violent and morally weak enough that he ends up destroying everyone and everything with whom he comes in contact. Phoenix’s only fault at times is his tendency to sound too modern.

Overall, “The Sisters Brothers” is photographed (by Benoit Debîe) and directed with a never-ending grunginess that makes it as much a mythic portrayal of the real West as any film of John Ford’s. A buffalo goring a horse in the night in a dense forest is a bit of a reach. However, its most stunning moment comes at the end. Without giving much away, the story’s memorable resolution boasts a precisely choreographed long single take, poetically lyrical and transcendently more moving than anything else in the film.

Written for the screen by the director and Thomas Bidegain while based on the novel by Patrick DeWitt, “The Sisters Brothers” is an existential examination of life in the American western wilderness.

“The Sisters Brothers” opens Sept. 21 in theaters nationwide.