‘Conversations With a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes’ Stares Into the Abyss of a Serial Killer’s Life

Alci Rengifo

A predatory ego proud of its own bloody trail, the voice of Ted Bundy speaks to us in Netflix’s chilling “Conversations With a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes.” True crime is an ongoing, morbidly fascinating trend in peak TV, but it never loses appeal because these stories have a way of capturing the darker side of human nature. With “The Ted Bundy Tapes” director Joe Berlinger allows the subject to be part of the narration, contrasting his own, twisted cadence with the testimonials of victims and law enforcement officials. Even if you have already read the details of the Bundy crimes before, the effect this 4-part documentary generates is unnerving, charting a life that became a nightmare that surpasses any horror film.

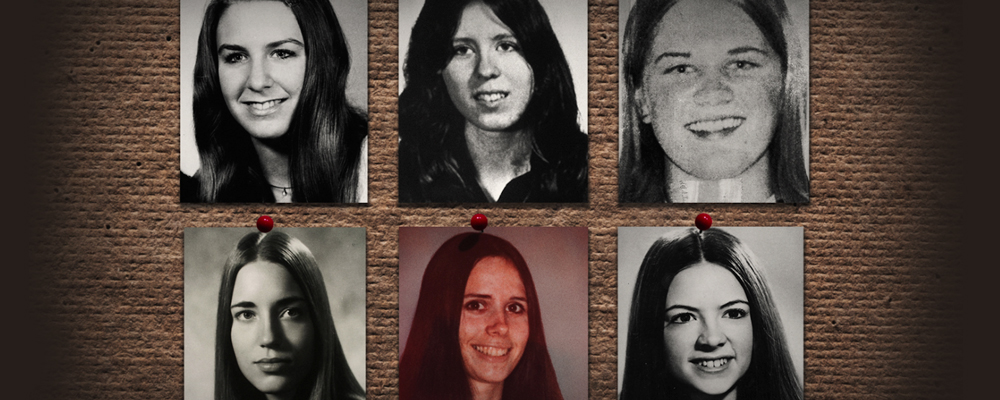

The documentary focuses on two journalists, Stephen Michaud and Hugh Aynesworth, who in 1980 decided to interview Ted Bundy while the convicted killer and rapist sat in death row. Michaud was the primary interviewer while Aynesworth traced Bundy’s murders across the country. Their plan was to eventually put the material together into a book. From 1974 to 1978 Bundy killed approximately 30 women, but the real number is generally agreed by authorities to be much higher. Handsome, considered to be charming and approachable by women, what drove Bundy to become a monster is a riddle his testimonial does little to clarify. What does come across is a raging ego. A child of the 1950s, Bundy grows up in Tacoma, Washington. Ironically Michaud lived nearby as well. Bundy’s childhood by his own account was not abusive and generally stable, yet contemporaries in the documentary share that he was also a loner, very much to himself. It was also obvious to those who would meet Bundy throughout his life that he was very intelligent, and soon he goes to study psychology in the University of Wisconsin, identifying as conservative amid the tumult of the 1960s. But soon a shattering breakup with a Stephanie Brooks seems to initiate the breaking point for Bundy’s psyche, and as on the surface he seems to live a normal life, in reality he has started channeling his inner rages through murder.

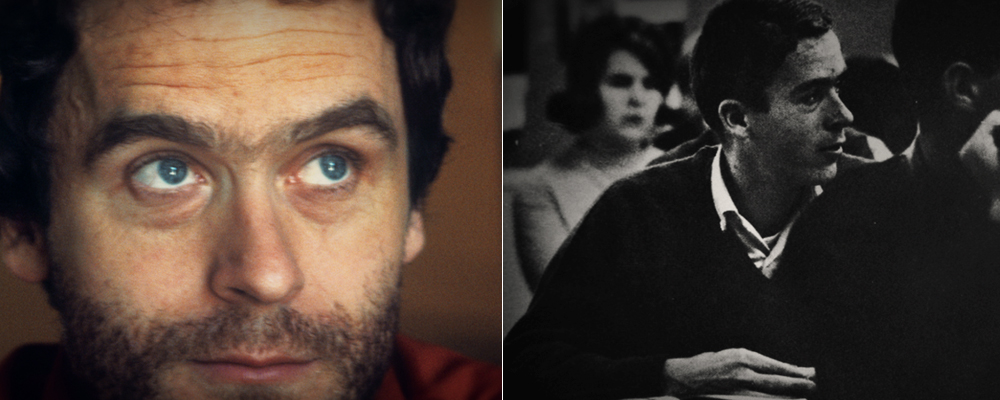

Joe Berlinger has captured enduring tales of crime and imprisonment before, particularly in the stunning “Paradise Lost” trilogy about the West Memphis Three case. Because we already know Ted Bundy committed his crimes and was executed in 1989, the power of this docuseries is the portrait it forms through Bundy’s odd words which range from tempered remembrances to obviously delusional efforts at denial. He was a well-spoken psychopath, at times evading Michaud’s questions with the skill of lawyer. “I’m particularly fond of looking at things in a chronological way,” he tells Michaud so nonchalantly. His story is like the American Dream gone off the rails. Hounded by who knows what insecurities, Bundy portrays himself as a social animal who could weave into any situation. This is the archetypical story of how you can never really know who you might be meeting. He works for the re-election campaign of Wisconsin governor Dan Evans and hangs out at social functions, wining and dining with politically connected people. Soon he will be breaking into the rooms of coeds to kidnap and mutilate his victims. Always in the recordings Bundy sounds like an ego demanding all the attention, feeling he’s owed status and applause. What is indeed most fascinating about Berlinger’s approach is how Michaud’s tapes serve as a landscape of abnormal psychology. Michaud recounts how he struggled with getting Bundy to describe or even admit to his crimes, so he decided to guide the killer into speaking in the third person. This was apparently the necessary trick and soon Bundy’s voice takes on an eerie tone, describing how a man might be driven to violent fantasies which he then acts out on his victims, but of course he is speaking about himself kidnapping, strangling and getting rid of victims.

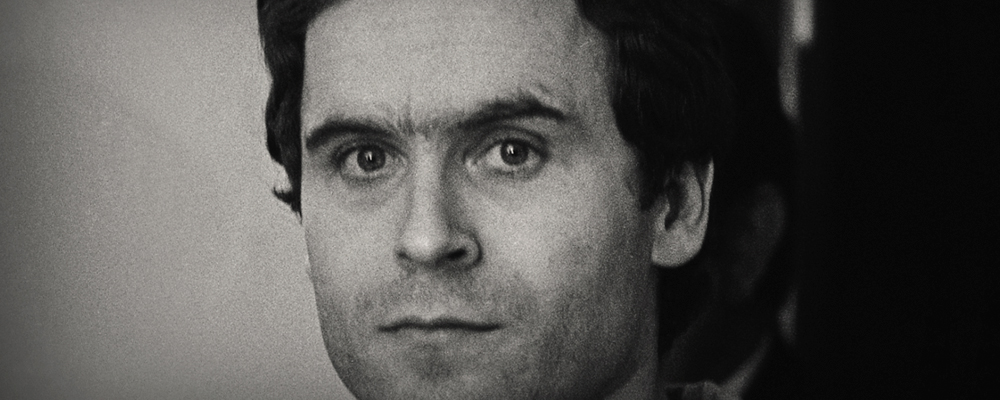

Berlinger juxtaposes the recordings and interviews with participants, including Bundy’s defense lawyers and detectives who had the horrific task of analyzing the crime scenes, with news footage and vintage film clips that work like nightmarish snapshots. It was easy for Bundy to lure unsuspecting victims because of his demeanor, well-groomed and charming. But look closely at the eyes, the ticks in the face, the egomaniacal grin, and it is obvious the man is not well. Berlinger poses the disturbing question of why such figures slip under people’s radars, and why they still project an allure even after being caught. One of the most disturbing moments comes in the fourth episode, when Bundy’s defense lawyer marvels at how young girls would try to slip him notes in court. So delusional was Bundy that he insisted in being his own defense while on trial, turning the court into a bizarre circus where he would quip and filibuster like a jester trapped in his own hallucination. When he is convicted and sentenced to death, the judge can’t help but observe that Bundy would have been a good lawyer, and makes it a point that he has no animosity towards the convict. Bundy even finds a devoted woman to fall in love with him and who has his child knowing he will never leave prison. One just can’t make any of this up.

“The Ted Bundy Tapes” has some of the same disturbed atmosphere of Netflix’s brilliant drama series “Mindhunter,” based on the book by profiler John Douglas, who appears here in clips when the FBI begins interviewing prisoners like Bundy to build criminal profiles. Sections do have the visceral edge of memorable true crime, as when Carol DaRonch, a teenager in Utah during Bundy’s spree, remembers being kidnapped by the madman and somehow finding the strength to escape. But instead of suspense there is a sense of unsettling tragedy. Bundy crossed into an abyss from which he never returned, targeting women out of fierce and sick rages in his broken psyche. His mother, who seems so regular, as if out of a Norman Rockwell painting, can only look bewildered when her son is exposed as a brutal predator. Up until the end Bundy remained the example of a deranged, murderous ego, finding time right before the electric chair to do a last interview with right-wing Christian media figure James Dobson, blaming his actions on too much pornography.

Berlinger has become so immersed in this story that later this year he is releasing an actual drama about Bundy starring Zack Efron, “Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile.” At one point in the tapes Bundy himself ponders how you can never know when you’ve met a killer out in society. And that is what continues to fascinate and disturb us, that Ted Bundy from afar seemed so normal and inviting. “The Ted Bundy Tapes” unsettles because it isn’t a thriller, all flash and plot twists. It’s about how real terrors can appear behind quiet eyes and an inviting smile.

“Conversations With a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes” premieres Jan. 24 on Netflix.