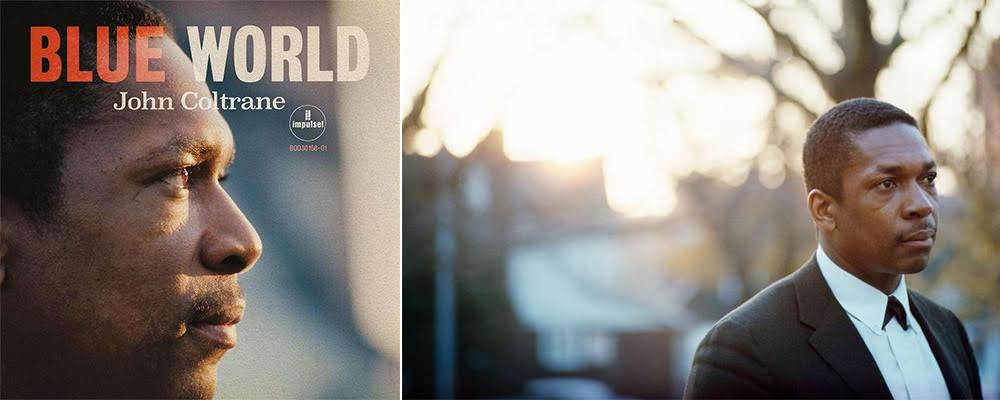

‘Blue World’ Shows John Coltrane Between Phases and Glowing

Adi Mehta

There are few figures in music more iconoclastic and enigmatic than John Coltrane, so any posthumous release is cause for plenty of fanfare. Last year’s “Both Directions At Once: The Lost Album” was both a critical and commercial triumph, which can raise some brows about another unreleased set of songs coming out so soon. However, “Blue World” has long been known among die-hard fans, who were aware that Coltrane once soundtracked the film, “Le chat dan le sac (The Cat in the Bag).” The 1964 feature debut of Canadian filmmaker Gilles Gloulx, is a French new wave production about two lovers struggling between visions of idealism and pragmatism in the context of Québec’s separatist movement. Gloux and his then partner and co-star Barbara Ulrich were massive Coltrane fans and requested that he soundtrack the film. Surprisingly, Coltrane, well at his prime, agreed to score this relatively unknown director’s project, with his classic quartet of pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Jimmy Garrison, and drummer Elvin Jones. Three songs made the film — one in whole, the others partially — amounting to an approximate total of ten minutes. But that was enough to make the film — because after all, this is Coltrane.

In the late ‘50s, on albums like 1957’s “Blue Train,” and 1958’s “Soultrane,” Coltrane pioneered and perfected the oversaturated “sheets of sounds” approach, stacking every scale imaginable simultaneously over each chord in a madcap, maximalist riot. By the turn of the decade, his “Giant Steps” initiated a collective, awestruck questioning of musical reality and a scratching of heads still vigorously in motion. By the following year’s “My Favorite Things,” he had settled into a more horizontal, modal mode — generally fewer notes, but sustained and expressed with passion. Ever the restless creative spirit, he would soon all but jettison Western harmonic notions altogether, come the vanguard free jazz lunacy of 1966’s “Meditations.” The new release “Blue World” was recorded in ‘64, just after the monumental “Crescent” and before the four-part devotional suite “A Love Supreme,” which rang as the epic realization of Coltrane’s long-teased spiritual inclinations. This temporal context is a key feature of “Blue World” as it finds the Coltrane quartet revisisting older songs — already a rare practice for Coltrane — at a distinct stage in their sonic evolution.

The album begins and ends with takes of “Naima,” originally from the “Giant Steps” sessions. The first of these infuses plenty new spirit and energy into the original recording of the song, which showed Coltrane as expressive as ever with the subtleties of his tone, but also at his most subdued and slowly reflective. This version gives the song a slight jolt, with Coltrane bringing the same melody further up front, and the rhythm section, especially piano, taking on a more conspicuous, active role, adding a bit more liveliness to the ambiance. This song, in entirety, was employed for the opening credits of the film, and it’s easy to hear its cinematic potential. The saxophone is known to be the instrument closest in timbre to that of the human voice, which accounts for much of its peerless emotional resonance. The slightest fleeting, impulsive wince at the right moment can make a world of a difference — and insofar lies the primary difference between the first and second takes on this record, with the latter a bit further removed and restrained. There’s a touch more of percussive interplay and quick piano flourishes thrown in here and there, but it has the overall feeling of a closer rather than an opener, as if the grand affair is done, and the band still plays on.

Two songs that make the album, “Village Blues” and “Like Sonny,” are lifted from 1961’s “Coltrane Jazz,” the first session recording of the Coltrane quartet, with all members other than Garrison, who came later and stayed until the end. Take 1 sounds sharper and more pointed, capturing all of the consummately coordinated swing of the original recording, and recasting it with the abandon of a seasoned band so comfortable in their own skin that one can just sense that they’re having fun, and it makes a palpable imprint on the music. Take 2, the one which made its way into the film, and appears earlier in the album’s tracklist, is not exceedingly different, but packs more of a punch percussively, with Jones still employing all of his slick tricks, but taking more of a head-on approach, rather than residing coolly just behind the pulse, and Coltrane’s melody especially pronounced and emphatic. In the film, it plays during a brief sex scene, with a clip in full volume just long enough to accentuate the steaminess on display, then fades into the background, and gains volume again as the two paramours walk giddly in the street. As the more sprightly, vivacious take, it certainly seems like an apt choice. As for Take 3, it’s the mellowest of the three, more capricious percussively, but altogether revisioned with an ever so slightly more laid back aesthetic.

As for “Like Sonny,” the song is, as you might guess, a reference to fellow saxophonist Sonny Rollins, as it was something about Rollins’ phrasing that gave birth to the song. Full of sinuous, serpentine lines that seem to emanate effortlessly, it’s a bit of iconic Coltrane. The version on “Blue World,” however, comes across as less impactful than the original. It’s looser, with more of the feeling of a free jam — and even though this is jazz after all, a track like this, which is already so boldly free in essence, can lose ground, and compromise its general resonance, when both the rhythm section and Coltrane himself take too many free liberties. The original howled and awed within tight parameters, while this one makes jabs at angles of brilliance in slipshod surges.

The title track is a variation of Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer’s “Out of This World” which opened 1962’s “Coltrane,” and has been speculated to have been tweaked and renamed for copyright concerns. This is a decidedly smoother affair than the busy, frenetic original. Coltrane is still bending and twisting in elegantly convoluted, histrionic whims, but over an eased-up, toned-down backdrop. In an album full of lingering notes and subtle gestures, this is quite easily the flashiest track, and while only half the running time of the original inspiration, it has enough acrobatics in that duration to give you a stirring jolt of a reminder of Coltrane’s range, and why he’s such a legend in the first place. The earliest throwback is “Traneing In,” excavated from 1957’s “John Coltrane With the Red Garland Trio.” This time, the new rendition is a considerable departure, beginning with a bass solo. With all due respect to jazz bassists, it’s quite safe to say that in the public eye, that low of register doesn’t exactly lend itself to extended solo passages in the most accessible way. In that regard, this is one for the real jazz insiders. Otherwise, it builds anticipation, so that when the band finally erupts in wondrous harmony, it’s a cathartic release, and much like the title track, this song recaptures all the vigor and passion of the original recording, but condenses it into half the time successfully.

Altogether, “Blue World” isn’t exactly an album in the proper sense, considering that there are only five songs, just a couple with multiple takes. Then again, jazz is an improvisational art, so hearing multiple takes alongside one another is a special treat. The subtle, instantaneous, different choices that make their way into the emergent hive mind, and end up creating an entirely new sound from the same compositional template are part of what makes a record like this so adventurously enjoyable. The set of songs also stands out because of its placement within Coltrane’s wildly versatile career trajectory. Fans will get a thrill out of hearing songs from previous eras reimagined years later, buttressed and informed by all the growth, shifts, and circumstances that made their way into the interval. Finally, it draws attention to the often overlooked cinematic appeal of Coltrane’s music, and should compel listeners to see, for themselves, how well his music translates to the screen.

“Blue World” is available Sept. 27 on Apple Music.