‘Atlanta’s Missing and Murdered: The Lost Children’ Tells the Human Stories Behind an American Tragedy

Alci Rengifo

Between 1979 and 1981 30 African-American children were found murdered in Atlanta, Georgia. This infamous case has gained a particular spot in the annals of American crime. Per the authorities it’s a solved atrocity, with Wayne Williams serving time in prison for two murders but tapped by the FBI for committing the others as well. Forty years later and the story is revisited in HBO’s new docuseries “Atlanta’s Missing and Murdered: The Lost Children,” which in five episodes goes over the entire dark moment while insisting on asking whether justice has been served. The question reaches to the heart of a case which goes beyond murder and connects to ever present chasms in American life.

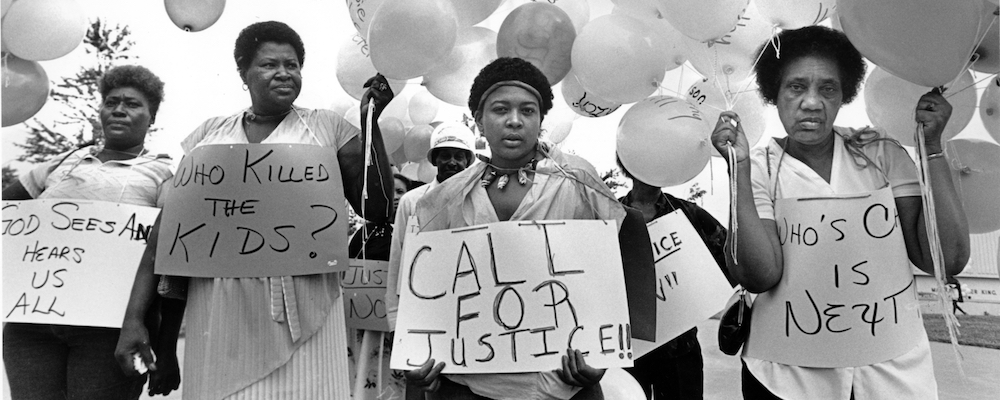

Cutting between stock footage of the past and developments in 2019, the docuseries encompasses the whole span of the child murders. They were frightening in their sudden, horrible simplicity. In Atlanta’s heavily black areas a kid goes out for a walk, to the grocery store or anywhere else and vanishes. This was happening at a time when Atlanta was cementing its reputation as a shining example of black prosperity in the United States. Sure the Ku Klux Klan was still around, even within the police department, but at the time Atlanta boasted the first black mayor in the south, Maynard Jackson as well as a social fabric composed of both activism and a black middle class. But once the disappearances and killings began they also brought along the ghosts of history. Class and racial divisions, a historic mistrust in local authorities all add to a high pressure environment. To this day the eventual arrest of Wayne Williams has left no sense of closure, prompting current Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms to reopen the case.

Recently the Atlanta Child Murders have received renewed attention, particularly as a worthy true crime subject. Last year the case was the major storyline for the final episodes of Netflix’s “Mindhunter.” Directors Sam Pollard, Maro Chermayeff, Jeff Dupre and Joshua Bennett avoid approaching what happened as a real life thriller. There is a different kind of urgency at work in the material, and it stems from the way these murders work as a shattering of American daydreams. Veteran black activists appear on camera describing the contrasts between reality and social fiction. Civil rights leaders would see Atlanta as an oasis from the more volatile, violent south where black colleges were flourishing and producing a potent workforce. Yet ghettos were still a harsh reality for the low-income class and it was from housing projects and surrounding zones that a good portion of the child victims were taken.

The first two episodes, made available for review, set the scene and introduce surviving family along with vital historical context. Much of the interview material is powerful when a mother still weeps when remembering their long ago murdered son, or a sibling still haunted by the memory of a disappearance. Reporters from the era recall the blatant political and media biases which attempted to find excuses veiled in subtle racism, for example it was common for newspapers to suggest it shouldn’t surprise anyone that kids from drug-dealing neighborhoods should meet tragic ends. It’s not shocking to see why activists then began forming self-defense neighborhood patrols. This was a city where it took years for black police officers to be given permission to arrest whites. A tragic explosion at a daycare center only helped fuel more paranoia. Volunteer search teams would find bodies in areas where the cops claimed there were none. How is a society expected to trust its centers of authority in such a situation?

Yet there was an arrest and “Atlanta’s Missing and Murdered” begins with this fact. The question is whether Wayne Williams did kill all 30 children. He was only convicted for two murders where the victims were adults. The docuseries paints a portrait of Williams as an intelligent but odd personality. He was a freelance photographer and self-trained DJ, at one point he billed himself as a talent scout looking for “the next Michael Jackson.” When FBI profilers arrived in Atlanta their immediate conclusion was that the killer had to be black, because racial divisions were so acute it would be impossible for a white killer to go unnoticed in black neighborhoods. The hint by those still demanding conclusive evidence is that Williams was a convenient target. The rest of the docuseries will then explore precisely why there might be reason to doubt this case is closed.

As a chronicle of crime “Atlanta’s Missing and Murdered” is a haunting experience. Not only do family members and others who lived through the events speak, but we see the actual crime scene photographs. To see the strangled body of a young victim brings home in all its horror the reality of the nature of what took place. Vintage footage shows us an 80’s world where the racism of the Jim Crow years was not fully stamped out. In a moment of rather dark irony we also get to see a PSA recorded by Bill Cosby warning kids not to talk to strangers.

This is a docuseries that has the spirit of both historical chronicle and ongoing investigation. It bridges the past and present with great force, reminding us that what happened years ago still casts a shadow today, not just on individual lives but society as a whole. Many in Atlanta feel justice was never served for those 30 murdered children, for them it’s another example of many reckonings yet to come in our ever changing eternally conflicted nation.

“Atlanta’s Missing and Murdered: The Lost Children” premieres April 5 and airs Sundays at 8 p.m. on HBO.