‘Rewind’ Searches Through Painful Memories in the Pursuit of Healing

Alci Rengifo

Our lives are part of vast chronicles captured through pictures and video. Not all such documents of our existence record only joy, some may hide truths more terrible to understand. “Rewind” is filmmaker Sasha Joseph Neulinger’s reckoning with a scarring experience from his childhood through the home videos that on the surface portray smiles and laughter. Yet they also hide a nightmare. Neulinger was the victim of sexual abuse as a child. Like many victims his attackers were also members of his family. However Neulinger is not on a quest for justice in the typical sense we find in most documentaries. People did go to jail. Neulinger is instead coming face to face as an adult with his memories and the need to process everything that happened.

“I was 23 years old and was just finishing film school at Montana State University. Quite a few years had passed between when I left for school, the end of the child abuse saga I had endured, and the age of 23,” said Neulinger as he shared with Entertainment Voice on the making of this devastating testimonial. “While I was trying to move forward with my life, and in many ways I was, there was still this nagging voice in the back of my mind, this victim voice of ‘you’re dirty, you’re disgusting, you’re unlovable.’ And that voice really was bothering me. I had a choice to make at 23. It was either live with this voice for the rest of my life and just try to ignore it, or figure out where it’s coming from and deal with it so it doesn’t keep negatively impacting my life.”

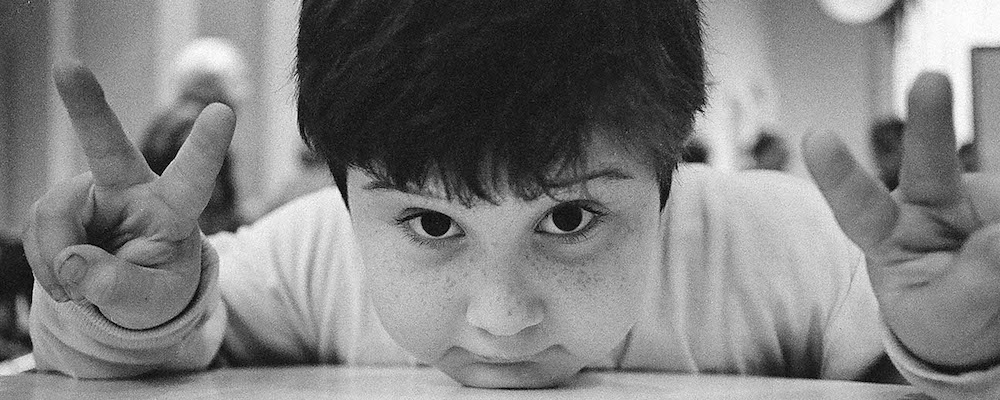

“Rewind” feels like a documentary as witness. The camera follows Neulinger as he remembers his childhood through the ‘90s home videos amassed by his father Henry, a broadcast journalist who became entranced by the emerging camcorder culture. In his early childhood Neulinger was signaled out by teachers as a gifted kid with high intelligence. But then as he continued elementary school Neulinger began to regress. As the documentary continues with Neulinger sitting down with Henry, his mother Jacqui and even his child psychiatrist, Dr. Herbert Lustig, the awful story of how he fell into the void of family predators reveals itself. There were two key abusers, his paternal uncles Larry, an exuberant wannabe funny man, and Howard, cantor of the Temple Emanu-El in Manhattan’s Upper West Side. We get to know them through Henry’s videos which show them goofing off, lounging around like any regular family. And then there are those small, brief moments, like one of the uncles holding a young Sasha, or close ups that hint at personalities masking themselves behind exuberance.

“I thought maybe I’d start by watching some home videos, maybe there’d be some answers in there,” said Neulinger. “I called my dad and asked him if he still had some home videos left over from when I was a kid. To my surprise he said he had three huge boxes with over 200 hours of home video. So after I watched the first six tapes I realized I needed to watch all of them. That was when I realized that this was going to be a film because those six tapes answered so many questions for me. Yet for every answer that I got I had ten new questions. This was going to be an ongoing conversation and I couldn’t even begin to comprehend where it would lead.” Sensing this would be a cathartic experience, Neulinger made the decision to be filmed as he revisited a hurtful past with his parents, intercutting these moments with selections from the home videos. “I wanted to make sure I watched every second…we’re dealing with multiple formats, VHS, Beta… I felt like I was going on an anthropological journey in a way. It was dusty and analog and foreign, it really felt like I was dipping into the past. A lot of these tapes weren’t labeled. So I could have one moment where I’m watching an absolutely beautiful, joyful moment from my childhood, a moment I had completely forgotten about because it had been overshadowed by the trauma. That would be this beautiful experience. But then in the same tape there could be a cut and all of sudden one of my abusers would be doing some weird stuff in front of the camera. It was jarring.”

Among the other materials Neulinger uses to tell his story are drawings he made as a boy in his psychiatric sessions which are eerie, powerful inner expressions of what the bright child we see in the video clips was carrying inside. Through these drawings Neulinger revealed at the time that his sister Bekah was also being abused by Larry’s son, their cousin. “Once I recognized the value in the home videos, I quickly started asking family members to send me boxes of photos. I started to recognize there were archives within different collections that my family members had. So I became curious as to what Dr. Lustig might have as well. The process of making ‘Rewind’ for me has been honoring my subjective childhood experiences and juxtaposing them with these new objective adult conversations to recontextualize what happened… I remembered making those drawings. I remember the relief I felt in being able to expose what was going on. To hold those drawings again, to see the crayon, it brought me back to a time when I drew those drawings and yet I was still in the present moment where I could contextualize it as an adult. It was powerful… how does a kid know how to talk about child sexual abuse? Most kids don’t know what is, they just know what happened to them feels awful… it’s hard to put into words what those emotions are. Drawings are such a powerful tool. They were a powerful tool for me then and a powerful tool to convey what I was feeling.”

Neulinger was able to tell adults like Dr. Lustig what was going on and as a result his abusers were arrested and taken to trial. While Larry eventually confessed, Harold was able to use his influence as a major figure in Manhattan’s Jewish community with political connections to avoid jail time. Yet the past refuses to stay dormant and “Rewind” is precisely about coming to terms with wounding events and their lasting impact. How abuse becomes cyclical in a family provides an urgent theme. Neulinger’s father Henry was not an abuser, but Larry and Harold had abused him growing up, and in turn their parents had toxic attitudes which set the terrain. We see them as siblings prone to jokes and gags, but Henry will then discuss how it was a trait taken from his mother, who refused to discuss anything emotional or unsettling, hiding behind humor like a shield.

“Basically I was inviting my family to join me in reopening but then taking the time to very carefully clean out our old wounds,” said Neulinger. “Nobody wants to do that because it hurts. For me surviving wasn’t enough. I wanted to truly move forward with my life and I really felt that unless we talked about this from every angle we’re never going to process it as a family. We’re never going to really be able to move on. I will honestly say my relationship with my parents and sister today is so much more joyful and open and honest and loving because we’re not locked in through the connection of our shared trauma anymore. We’ve recognized the trauma, we’ve faced it, discussed it. It’s allowed us to have new and beautiful experiences that are independent of what we endured in our past.”

“Rewind” may be an emotionally difficult experience, but it is a necessary one. The value of many great documentaries is to generate a particular sense of empathy. Neulinger’s story is that of countless others. This work is just one voice. “Each human being has their own unique experience with trauma and their own unique journey towards healing. While I can’t speak to every survivor who’s been through this, what I can do is speak to my own experience… I would honestly say that when I dealt with that wound and cleaned it out, which was extremely hard, it terrified me and rocked me to my core at times, but it was the best decision I could’ve ever made for myself. I can talk about what happened to me. It doesn’t trigger me. It doesn’t make me feel like less of a human being. In fact I’m reminded that what happened to me is just that. It happened to me. But it doesn’t define who I am or makes me any less of a person. I hope other survivors can get to a place where they feel that themselves, because it’s truly empowering.”

“Rewind” premieres May 8 on VOD.