Mark Mothersbaugh on His New Art Book, DEVO, and Composing for Film and TV

Brianne Nemiroff

Whether you know it or not, the music of Mark Mothersbaugh has been a staple in your daily life over the last 35 years. A founding member of the band Devo, known for their hit “Whip It!,” Mothersbaugh has also scored many commercials for soda, retail and car brands, and was the music behind children’s shows like “Clifford the Big Red Dog,” “Pee-wee’s Playhouse” and most famously “Rugrats.” (Who doesn’t know that theme song?) And since composing music for The Rugrats Movie, he has scored five films for Wes Anderson, including The Royal Tenenbaums and The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, and for animated films, such as Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs and The Lego Movie.

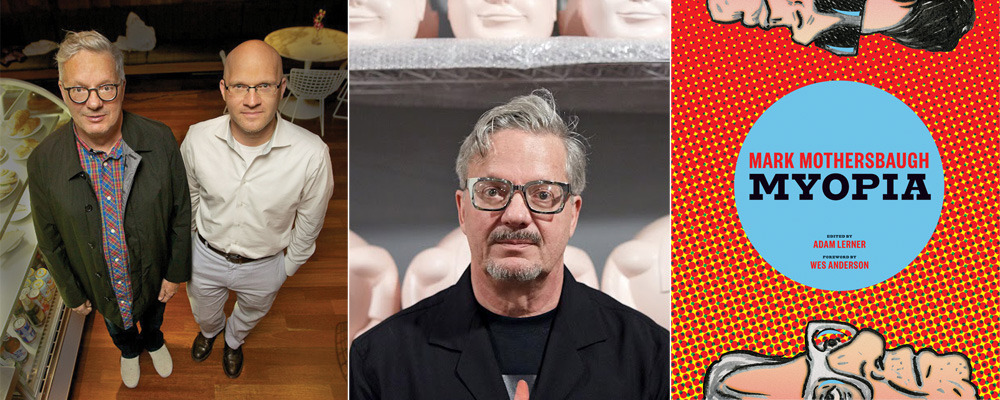

While he mostly known for his music, Mothersbaugh is also an artist in all definitions of the term, as he loves to paint, draw, create decals and do so much more. He is someone that’s hard to contain artistically, but he’s inherently a storyteller whether the art is visual, musical or vocal. And to celebrate his life-long love of art, Mothersbaugh is releasing his first book “Mark Mothersbaugh: Myopia.”

The art book features a lifetime of Motherbaugh’s paintings, photographs, sculptures and rugs. There’s also a foreword by Wes Anderson, an in-depth interview with Mothersbaugh and other essays. To accompanying the book release, a six-city traveling exhibition will start at Denver’s Museum of Contemporary Art. And on October 2nd, Los Angeles will host an intimate evening with Mothersbaugh in conversation with Adam Lerner, the book’s editor and Denver MOCA’s director/chief animator. The event is free and open to the public, and there will be a book signing after the talk.

Mothersbaugh is one of the most influential people in the indie art/music scene, and he recently sat down with Entertainment Voice to discuss the origins of Devo, how being nearsighted was a factor in his love of mail art, and why he is forever indebted to “Rugrats.”

Your book “Mark Mothersbaugh: Myopia” features so many kinds of art and memorabilia. Is this your version of a memoir?

MM: Yes, or an explanation. It’s a memoir of sorts.… I’m going to talk about Devo because I’m fond of it and that’s when I was a young artist. [With Devo] I met with these other guys and we all came up with something that actually became our life, [these] political stories. We decided at an early age to become musical reporters and report on mankind on the planet. I think this book is an attempt to pull together [things] that were never revealed before. I led a life where you can find five people who all know me for totally different things. [One will say], “Oh, he had two number-one films this year.” [Another will say], “Oh, I saw him at Mabuhay Gardens in San Francisco and he threw himself off the rafters.” Or there’ll be a 2-year-old that will point and say, “Yo Gabba Gabba!”

What particular things can Devo fans look forward to in the book?

MM: The book isn’t about Devo, except that this [was] the starting point, what happens when the guys go off in their separate ways. Hopefully you’ll see a thread of permutations of what happened. While we each developed into different artists, we all still carry the DNA that came from the original collaboration. I probably wrote most of the music in Devo, but it was always a collaboration, no matter who gets the credit. Nobody worked in a vacuum. They’ll see where we started and [that] it was a collaboration with these other guys, primarily with Gerry Casale.

[Gerry and I] were both in the art department. We had found a book called “The Beginning of the End” by a Yugoslavian anthropologist, in spite of the [world] discrediting him. He’s the first one who really started saying that we’re all experiencing a de-evolution, rather than evolution, as a way to think about art, music and life. [As Devo] we put that into action. Gerry was the first conceptual artist that I ever worked with and he influenced me a lot and we gave each other focus. It was a very symbiotic relationship. We were different halves of something bigger. It propped both of us into the world.

Visual art and music are both means of artistic expressions. Since music is your profession, is it still your go-to for personal means of artistic expression? Or are you drawn to other mediums first in your personal life?

MM: To me, there was never a clear separation. It was never for us to make those separations. We were constantly trying to sew them together. Gerry was directing our films, [and] we were doing the album graphics, designing our costumes and merchandise. We did the majority of our graphics ourselves. The separation was put on us by record companies who tried to separate our music from our art. They didn’t understand it and found it intimidating and irritating because they were just salesmen. Some people sell shoes, they were selling records in Manhattan and Burbank. They didn’t need someone to say, “We’re going to turn the world upside down,” [and that] “Film, sound and vision are the future.” [Devo] was [labeled as] weird and quirky as the [idea] they could deal with and understand and still let us do what we wanted, and still put us in record stores.

Gerry and I loved pop artists, [like] Dada and Warhol. [Warhol] was painting, drawing, doing screen prints, making movies and designing fashion. He also [worked with] the Velvet Underground and threw the best parties in Manhattan. That’s such a cool way to live your life and blur those lines.

How do you go about a new piece of art? Does it depend on the medium? What kind of art do you gravitate towards?

MM: I’m extremely nearsighted. A long time ago, just the fact of having a lack of materials to work with and not having a studio, while performing in the ’70s with Devo, we were traveling around in a van, staying wherever we could stay, [and] I started being interested in mail art. [I liked] these small-sized drawings that were easy for me to hold the perspective on because I could see the whole piece of paper at once. I was doing these drawings that were about four by six inches and I started saving them. Those paintings and those collages were my diary. I started putting them in these archival binders I found in a stamp supply store. [After] 100 drawings, I would put the binder on a shelf. I started off doing one a year and then I kept going. Forty years later, now there are 320 or 350 binders and they’re now an image bank for my personal projects. They became a source for both Devo and my own personal projects.

How did you transition from Devo to being a composer for television?

MM: After the band had done [nine] albums, we ended up with some downtime and a friend of mine asked me if I wanted to write the music for his TV show, and I said, “Sure.” It was “Pee-wee’s Playhouse.” [During my] first week on [that] Monday, he sent me a tape from New York to my studio in Los Angeles. I wrote the music on Monday [and] put it to the show on Tuesday. The whole turnaround was done by Saturday [when it aired].

I just got to write 12 songs in one week instead of 12 songs [in one year, and] I fell in love with scoring. As much as I liked doing albums, I saw this other occupation and it was this ideal experience. It was so much different than [working with] record companies. They would say, “Hey, guys, do whatever you want. Just do another ‘Whip It!’” [while] breathing down our necks so you can make them another million bucks this week. I ended up really loving doing this other project, and by not being on the road I had more time for visuals.

One of your biggest projects was “Rugrats.” The music was definitely one-of-a-kind and ahead of its time. Do you remember how you came up with the musical concept for “Rugrats”?

MM: Originally, [“Rugrats” Creator] Gabor Csupo wanted to use a track from an album I did called Muzic for Insomniacs for the theme. It had been in the early days of sampling. I had a very low-res sampler [that] did 8-bit sampling. It sounded like an old Atari game. What I liked about it was that you could sample an acoustic guitar, and it sounded like it but [also] sounded like you went to Walmart and bought the vinyl wood paneling of that instrument instead of real wood paneling. It was so plastic-y sounding. I sampled a lot of noises, because of the babies and everything about that show.

I will always be indebted to that show. I didn’t go to school to be a composer. I went to school to be a painter and printmaker. When I got out here, when it came to doing a feature film for “Rugrats,” Paramount originally said I couldn’t do the film. But Nickelodeon fought for it because I scored every episode and they were naive. They needed a 100-piece orchestra. You hear humans in the music more than guitars and a synthesizer. They bring it to life. It helps [the details] come alive.

For more details check out: “Mark Mothersbaugh: Myopia”