Archibald Motley Exhibit Brings Harlem to Los Angeles

Kirk Silsbee

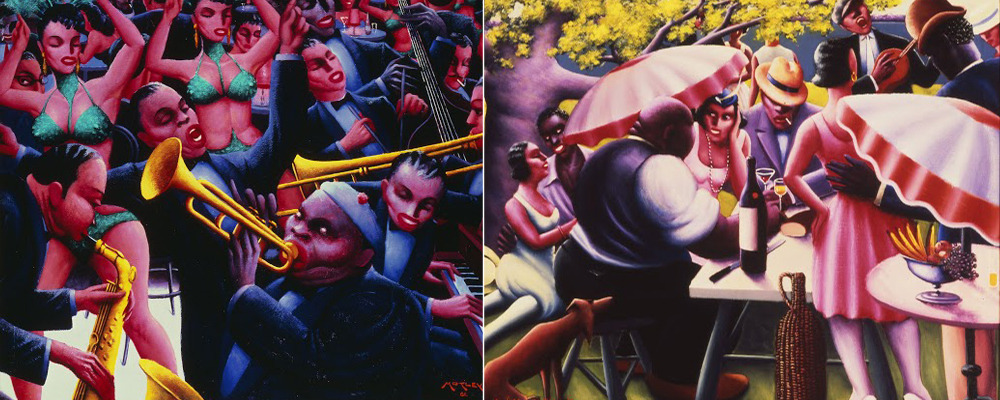

Archibald Motley Jr. (1891-1961) was the most famous artist of the Harlem Renaissance who never lived in Harlem. The New Orleans born painter grew up on Chicago’s southwest side, a predominantly white neighborhood, and graduated from the prestigious School of the Art Institute in 1918. Motley’s artistic scenes of gaiety and community had a universality that translated to and resonated with the cultural ferment that took place in the capital of black America, Harlem. So vivid was Motley’s artistic vision that he continued depicting black urban subject matter abroad, after being awarded a Guggenheim grant in 1929. His most famous painting, “Blues”—with its colorful compression of dancing couples and a jazz band—was made in Paris.

His work has had sporadic exposure through the years. The traveling exhibit Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist, at LACMA (Oct. 19-Feb. 1, 2015), debuted at Duke University’s Nasher Museum last January and makes a final stop at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art next year. It gathers forty pieces and is undoubtedly the biggest cache of Motley’s paintings to ever land in Southern California.

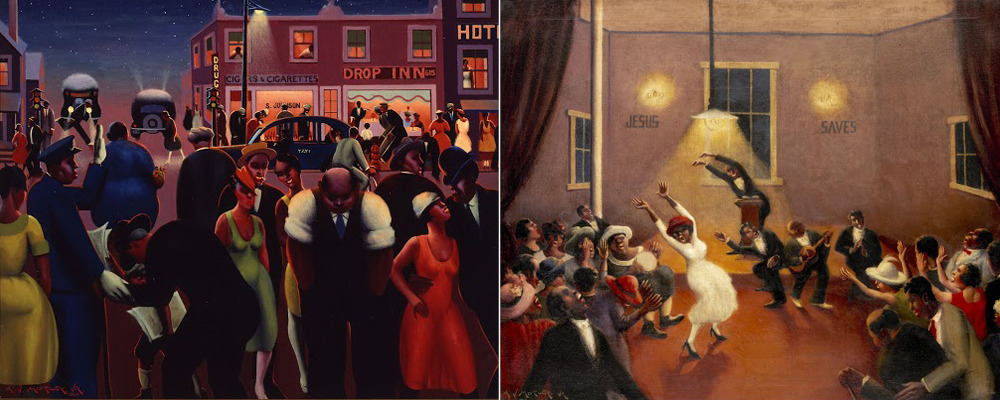

Those paintings vibrate with color, energy, and canny representations. Motley was a keen observer of his community and he deftly rendered various types of characters. His people are stylized, sometimes to the point of cartoon reduction, but they are instantly readable; the sports man with the tilted bowler, the bobbed hair secretary out for a night on the town, the working stiff trying to keep up with the swells at a party, the laborer throwing his money away on the fancy gal, the holy roller preacher leading his congregation, prostitutes languishing in view of their pimp, or pool hall sharpies. Though Motley worked in a folksy vernacular, his angular compositions and strong design sense betray his ties to modernism.

Like his Harlem contemporary, photographer James Van Der Zee, Motley’s work chronicles a population with migrant roots. They’re newly-arrived from the South or in various stages of acculturation, on their way to forming the black middle class. Where Van Der Zee’s people pose hopefully in their Sunday best, Motley’s subjects aren’t always so long out of the cotton fields.

Motley’s work also spoke in another voice, this one refined and quiet. He painted a number of portraits that imparted a combination of personal reality and aspiration. Some were probably commissions and, like Ingres and Van Der Zee, Motley’s subjects usually have their best foot forward. One of the earliest was “Portrait of My Grandmother,” (1922) a sober view of a hard-working mature woman with nothing around her. Another elderly woman, in “Mending Socks,” rests comfortably in a lace-trimmed parlor with a prominent crucifix watching over her. A couple of years later, “The Octoroon Girl” sits in a darkened room, smartly turned out in an evening dress and a pair of gloves. She stares at the viewer with composed confidence, or is it wary skepticism? Bathed, coiffed, powdered and nude, “Brown Girl (After the Bath)” sits at her vanity table with an air of self-satisfaction, and engages the eye through her mirror. Is she going out or staying in tonight?

LACMA’s Motley show gives us a chance to catch up to a past master whose work few of us have had a chance to adequately explore. It’s time to set aside time to finally do so.

Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist will be on display from October 19th, 2014 to February 1st, 2015 at the LACMA. For more information, click here.