‘Monk with a Camera’ Shares Insight on a Lifestyle of Simplicity

A Lawrence Dreyfuss

Monks are simultaneously very open to the world and seemingly allusive. The separation between West and East makes Buddhism seem unknowable to many in America. To reach the temple of the Dalai Lama, the best-known living monk in the world, requires a flight to Delhi, a bus ride of several hours to the north, and a winding walk through the bustling city of Dharamsala.

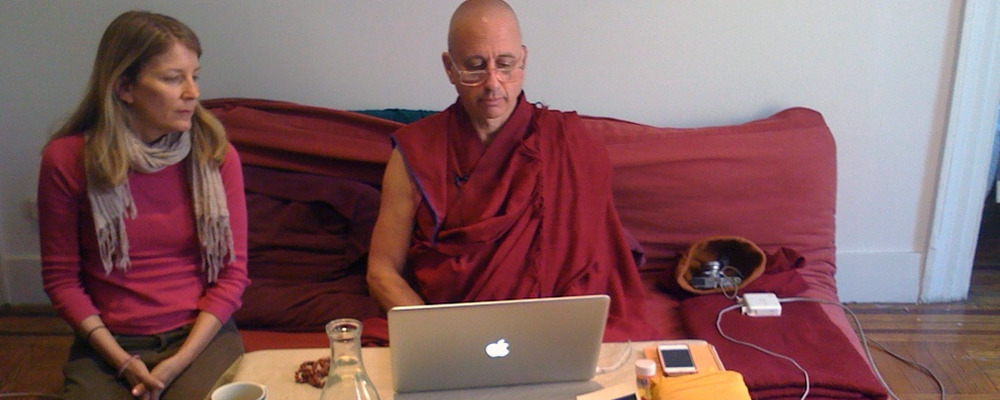

Buddhism, specifically Tibetan Buddhism, teaches a culture system that values the relinquishing of worldly possessions and an embracing of modest living. Keep this in mind when you consider the childhood of monk Nicholas Vreeland. Nicholas grew up in the upper echelon of New York aristocracy. He is the grandson of Diana Vreeland, previous editor of Vogue, and lived the life that his family legacy would imply. He regularly wore tailored suits, drove fast cars, and dated renowned models. His life was centered on material wealth.

How is it that he decided to cast all this aside and become a Buddhist monk in India? That is the topic of the latest documentary from co-directors Tina Mascara and Guido Santi entitled “Monk with a Camera.”

“Monk” unfolds narratively as two distinct stories interwoven. The first story is Vreeland’s childhood of falling in love with New York, taking vacations in southern France, and studying in Paris. The second story is about the Rato Monastery where Vreeland has spent more than a decade of his adult life. When he arrived, it was little more than a hole in the wall but over his tenure there, it grew into something great. The thing that unites the two stories is a camera and it is a recurring trope in the movie. As a teenager, Vreeland fell in love with photography and so when he moved to India he decided to take a camera as well. The theme of photography is present both in the subject matter and in the medium of presentation.

What the film offers, as no film has before, is a look into the world of devout Tibetan Buddhism through a perspective that is similar to our own. The cinematographer follows Vreeland around with the excitement of a student learning from a master, not unlike many of the relationships documented in the movie.

For much of the movie, it would be easy to wonder why. Why is it that the documentarian felt the need to tell this story now? The answer is revealed in the third part of the movie, but even despite this delayed understanding, the film never becomes boring. It thrusts forward at a delightful pace and integrates stories of youthful indiscretion with spiritual fervor. Those moments that are essential to Vreeland’s religious transformation are depicted in almost silly animation that, rather than seeming disrespectful, lends a jovial air to the proceedings.

The idea of a rich kid renouncing his wealth to live a life of piety sounds like a Hollywood screenplay, and as one person in the film points out, it may come across as cliché. Despite this, the movie has the unpredictability of reality. When Richard Gere shows up to discuss Vreeland’s story it becomes immediately clear that anything could have happened in this man’s life and the excitement of finding out what adventure will be explored next never dwindles.

For example, one sequence in the film explores the nature of hair. How did Vreeland mold it when he had some, and what was it like to shave it off? One interviewee explains that at the time if you were bald it meant you either had been recently released from a mental hospital or had just had brain surgery. The act of shaving Vreeland’s head could easily have been reduced to one line, but the film uses a combination of archival interviews, photographs and drawings to lend it a wit and charm that may not have been immediately evident. This is the strength of the film, making what might be seemingly mundane into something that is utterly enjoyable.

It would have been easy for “Monk with a Camera” to become bogged down with religious doctrine. After all, how can a director tell a story about religious conversion without talking about religion? The film makes the bold choice to sidestep an exploration of belief and make it rather about lifestyle. The thing we lose in the film is a clear image of Vreeland’s spiritual journey. It is not unclear why he chose a simple life, but the choice to do it as a Buddhist rather than, say, as a Catholic monk, is not entirely explored. What the film gives up to gain accessibility it loses in terms of philosophical depth.

Overall, Monk with a Camera is utterly enthralling and is definitely worth a viewing.

“Monk With a Camera” opens in Los Angeles Dec. 12.