‘Godard Mon Amour’ Paints Meandering Portrait of Cinema Icon Jean-Luc Godard

Alci Rengifo

Jean-Luc Godard is as colorful and fascinating a figure as his influential body of work. The maestro has donned many shades from film critic to film director to political radical. Now at 87 years of age, he is reportedly working on a new, international project after having released a 3-D movie in 2015. Surely he would make for a fascinating biopic. Instead “Godard Mon Amour” goes for a meandering approach, opting for a distant, cold portrait of the filmmaker. It follows Godard in the months of the May 68 unrest in France, as amid political battles he struggles with his marriage to a younger actress. But while this film certainly carries the slogans of the times, it never attempts to capture the man.

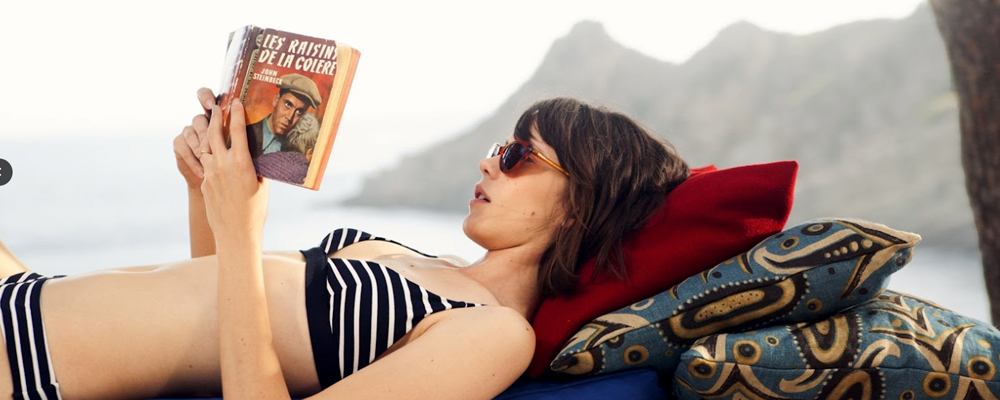

It begins in 1967 as Godard (Louis Garrel) films his latest movie, “La Chinoise,” which dramatizes the passions of Maoist students. The movie stars his new love and wife, Anne (Stacy Martin), who is 17 years younger. It has been a few years since Godard made his mark with groundbreaking French New Wave films like “Breathless” and “Contempt,” now he is obsessed with the radical winds in the air. He takes Anne along to political meetings, has Mao Zedong portraits at home and gets annoyed when fans ask when he’ll make “funny movies” again. But the director soon becomes unbearable to Anne and their friends as he turns everything into a debate about bourgeoisie culture and “the revolution.” His radical postures also don’t make him immune to jealous fits when Anne appears to flirt with handsome, younger men, especially co-stars. Once the events of May 1968 erupt, Godard tries to live out his ideals even as he slowly becomes a bore.

“Godard Mon Amour” is the latest film from director Michel Hazanavicius, who won the 2011 “Best Picture” Oscar for the lively silent film homage “The Artist.” His take on Godard surprisingly lacks much life. One key mistake is that it separates the artist from the art. We never feel as if we are spending time with an actual film director. Nothing is ever presented or even described about Godard’s work, which is significant in the history of cinema. It’s as if “The Doors” had followed Jim Morrison around without including any of his songs. So viewers who might not be familiar with the French New Wave or Godard will have little to no context for the personalities on the screen. Even if he turns into a jerk, we should be given examples of what feeds his ego. The only time we catch a glimpse is in the opening scene, as he films a moment in “La Chinoise,” which is one of his more dated works (but still full of quirky energy). The bright, maddened talent that conjured the apocalyptic critique of capitalism in “Weekend,” or the noir splendor of “Breathless” is missing here. Even if Hazanavicius wishes to be iconoclastic, he must provide a decent context for his subject.

Because he’s in nearly every scene, the lead performance by Louis Garrel is no small feat. But what he given to evoke is a sort of caricature. His Godard is essentially a poseur activist, sitting around cafes and road tripping with his fellow bohemians while espousing Maoist rhetoric. He begins to feel the pull between the nature of his job and the attitude of his political affiliations. Ironically enough, in 2004 Garrel played a 60s French student in Bernardo Bertolucci’s “The Dreamers,” who praises Mao’s Cultural Revolution while sipping his parents’ expensive wine. There are some truly funny moments where Godard will be marching to the barricades and a radical student will ask when he’ll make something fun again. Godard’s reply, “when Vietnam, Yemen and Palestine can smile.” He goes to meetings and is distraught to find graffiti mocking him in the college hallways. The ultimate blow comes when even the Chinese government refuses to screen “La Chinoise.” Yet when the May riots break out he does at least walk the talk and starts hurling cobblestones at the police. These moments would work better if Hazanavicius had given them proper context. Nothing is explained or explored about what even caused the riots and subsequent general strike. It is all simply a series of events splashed onscreen, hoping audience members will simply Google it afterwards or already walk in having read up on the subject. The most darkly comic scene comes when Godard tries to make a point about Israel during a student meeting, choosing disastrously unwise words that get him booed. Master of oratory he was not.

The third act of “Godard Mon Amour” feels like being trapped with a couple that slowly starts loathing each other. Godard, as portrayed here, grows insanely jealous over Anne leaving to shoot a movie, feeling uneasy when she mentions she would do nudity if it makes sense in the story. He sits on beds, looking glum, until inevitably lashing out at Anne, saying pathetically, “you’ve turned me into some jealous loser.” It all becomes a depressing slog near the end.

There are some merits to this film however. Visually Guillaume Schiffman manages to capture the look and color schemes of Godard’s work. At times there are editing winks to Godard’s own pioneering style of intercutting (when you see an action movie hurl three images at you in rapid succession, you have the French New Wave to thank). The environment of the film feels like a complete trip back in time to the 60s, with small, rich details in the décor. Hazanavicius’s screenplay also has a good ear for the way political trends become a culture. Godard speaks for most of the movie in quick slogans, sometimes explaining his positions with Che Guevara quotes (“make another Vietnam in yourself”). The dialogue is a chronicle of how a different era was thinking.

The subject of “Godard Mon Amour” is worthy, but the film is not worthy of him. There are interesting ideas and sketches here, but the full portrait is missing. Godard himself once described his approach to filmmaking as, “cutting out the boring parts.” This movie should have taken his advice.

“Godard Mon Amour” opened April 20 in select theaters.