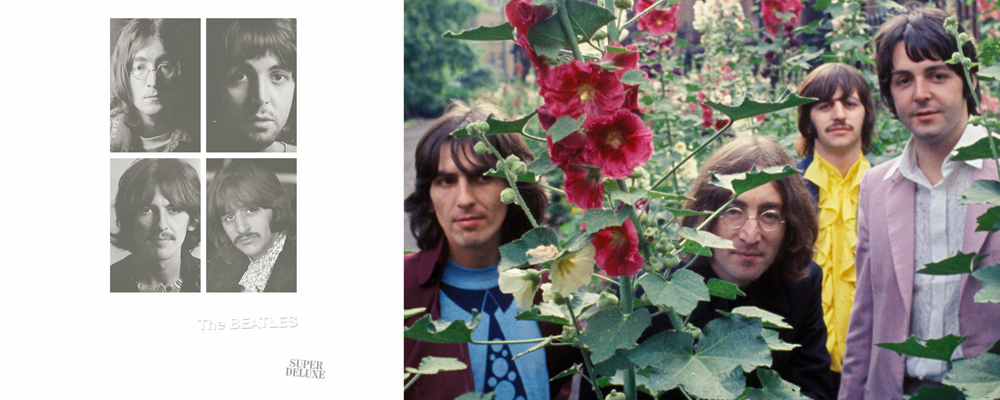

‘The Beatles (White Album) Super Deluxe’ Dissects and Revamps a Monumental Album

Adi Mehta

The Beatles‘ “White Album” denotes a distinct period in the artistic evolution of the biggest band in popular music history. Moptops had come and gone, supplanted by Eastern spiritualism and avant garde sensibilities. Now came a call for a decluttering, of sorts, and an overall sonic update. A double disc of thirty songs, the album proved an ambitious, era-defining work, seen by many as the group’s magnum opus. For its 50th anniversary, the album has been re-released in the form of a box set, titled “The Beatles (White Album) Super Deluxe.” The first two discs contain remixes of the original tracklist, mixed by none other than Giles Martin, son of legendary Beatles producer George Martin. The third disc features a selection of sketches known as the “Esher demos,” mainly stripped-down, acoustic versions of the songs that would come to be. The remaining three discs collect various takes — alternate or intermediate versions of known songs, or unreleased tracks — from the album’s recording sessions. Overall, the set offers a revamped auditory experience of the classic album,and provides a fascinating look into the the Beatles’ creative process.

One of the most striking aspects of the demos and alternate takes is how informal, whimsical, and often jokey the band is in the studio. Lennon and McCartney routinely try out silly voices, and make comical sounds. The Esher demo of “Back in the U.S.S.R.” ends with Lennon half-humming and half-singing in falsetto, apparently trying to mimic a distorted guitar. Moments like this show the band jotting down their ideas in real time, often in laughably crude form. Upon listening to the final versions of the songs, one can see how the ideas have crystallized from the preliminary sketches. Lennon’s songs often start with melodies not yet formulated, just words spoken over chords with levity.

There are several prog-leaning tracks on the White Album, with seemingly unrelated, distinct phases joint together. Often only one of these movements can be traced back to an Esher demo. For instance, the initial version of “Happiness is a Warm Gun” consists of only the bridge and chorus. John strums along and adlibs melodies in a more natural extension of these segments. In the final version, however, these bits are slipped and inserted within entirely new sections, giving the song its ambitious, epic form. The demo of “Rocky Raccoon” begins with the chorus, revealing the core around which the eventual track was built. Different takes provide a peek into the Beatles’ creative processes, showing tunes develop into songs, and assume arrangements.

Some of the included takes show the Beatles considering widely divergent approaches to individual songs. The Esher demo of “Blackbird” features McCartney singing in a softer, less enunciated tone. Take 28 of the song finds him trying out a voice more like the one that makes the final cut. After the song, you hear him discuss his uncertainty regarding which way to sing. “Julia” is another song that takes multiple forms. The guitar playing on the demo is finger-picked, note by note, but a later recording starts of with Lennon strumming the chords, only to stop, and revert back to the original approach.

Many songs on the White Album achieve their sound largely from elaborate production and fanciful arrangements. When stripped of all their dressing, and presented in barebones, acoustic renditions, they can take on an entirely different light. It is astonishing how “Yer Blues” has been transformed from a rustic, soulful ditty into a heavy, hard rock stomper, and how “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” is expanded from a soft,modest, contemplative piece to a sprawling, kaleidoscopic affair. On certain songs, the minimal instrumentation of the demos reveals an underlying groove lost in the final cut. Such is the case with both “Revolution” and “Honey Pie.” The demo versions are of a faster tempo, which makes for a more propulsive rhythm. There’s a special charm to the stripped-down versions — a certain elemental rawness, and a more folk sensibility.

There are a few unreleased Esher demos that could have been fleshed out into exceptional songs. “Junk” is a lovely vignette, with McCartney’s signature melodic phrasing conjuring the mood of such classics as “Yesterday” and “Michelle.” Harrison’s “Circles” is a dark, theatrical, droney track reminiscent of Pink Floyd in the Syd Barrett days. “Not Guilty,” another Harrison contribution, is an infectious number with oblique jazzy stylings that give it a cinematic quality. “A Beginning (Take 4) / Don’t Pass Me By (Take 7)” adds a lush,decadent, classical intro to the latter song, which the band oddly chose not to include in the mastered version.

There are short, slapdash unreleased tunes, interspersed within the various takes of known songs, that show the band having a bit of fun. McCartney’s choice to tackle “St. Louis Blues” sheds light upon his headspace during the recording sessions. Indeed, we can see such influences seeping their way into the music in the retro blues stylings of songs like “Honey Pie.” There is also a stretch of songs that finds the band given over to a bossa nova aesthetic. In between takes of “I Will,” the band maintains the world percussion and minimal, syncopated rhythm of that song, for a cover of the classic “Blue Moon.” “Los Paranoias” gets downright cartoonish, with McCartney warbling, yelping, and scatting. “(You’re so Square) Baby, I Don’t Care (Studio jam)” is a Rockabilly flurry, with McCartney doing his best Elvis impersonation, in the tradition of the Beatles’ early days as a straight rock ‘n’ roll band. It’s a harbinger of the return to roots that would characterize the band’s sound on “Let It Be.” The title track of that record show up here, in a hardly recognizable form. The band jams out in a casual, steady groove, over which McCartney hollers the chorus lyrics without any trace of the melody that would eventually string them together.

There are early versions of songs that would see later releases, like “Lady Madonna” and “Across the Universe.” Simultaneously, there are unreleased tracks that recall different eras in the Beatles’ evolution. The White Album marked a departure from the wigged-out, acid extravagance of “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,” for more stripped-down stylings, along with a bolder, more modern rock sound. Yet, some of the songs from these sessions are very much of the ““Sgt. Pepper’s” phase, for instance “The Inner Light (Take 6 – Instrumental backing track),” which delves into psychedelic territory with its Indian-styled instrumentation. “What’s the New Mary Jane” is the type of frivolous lunacy that characterized much of “Magic Mystery Tour.” The presence of such songs in these sessions reveals the band in a transition phase.

“The Beatles (White Album) Super Deluxe.” gives an intimate look into a monumental album, bringing you front and center into the studio with the band. It shows the musicians baring themselves raw and pure, and captures them toying with ideas, and experimenting with sounds and arrangements. Hearing the songs develop and take form, stage by stage, forces you to acknowledge all the detail, as well as the compositional and production choices, that went into the recording. As for the remixed version of the album, it recasts the classic sounds in a new layout, offering a novel variation that packs an extra punch. Altogether, the box set functions as both an insightful documentary on an epic recording, and an immersive update on the recording itself.

“The Beatles (White Album) Super Deluxe” is available Nov. 9 on Apple Music.