‘Leaving Neverland’ Lets Michael Jackson’s Accusers Tell Their Side of the Story

Alci Rengifo

More than almost any other recent documentary, HBO’s two-part “Leaving Neverland” challenges our perceptions of a cultural icon. It features two accusers claiming the late, pop titan Michael Jackson sexually abused them as children, providing graphic, searing testimonials. Already this is proving to be a highly divisive work, inciting a firestorm of public and online debate. It is true that Jackson was acquitted in a court of law, and it is certainly true that a film or documentary should never be the final judgement on anyone. But that does not mean that Wade Robson and James Safechuck do not deserve to tell their stories. As the #MeToo era has demonstrated, it is not easy to call out the powerful on their abuses. Director Dan Reed is giving a voice to those usually left without the resources allotted to the other side.

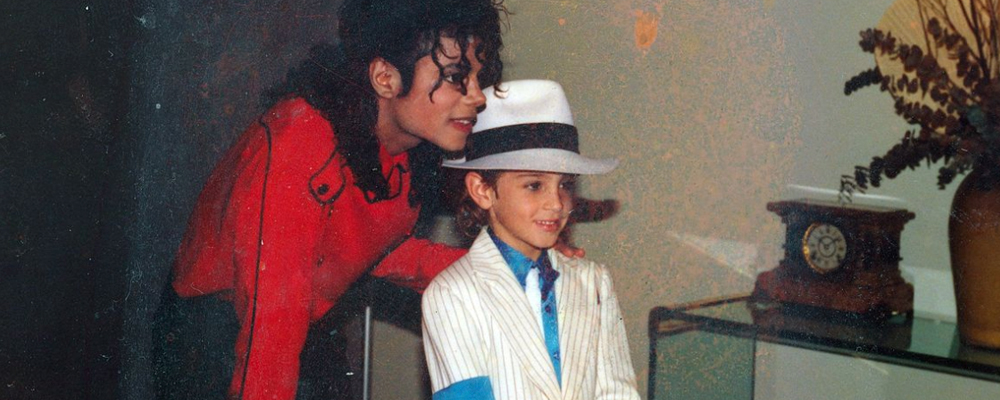

Robson and Safechuck narrate how they first met Jackson in the late 80s and early 90s. Robson was an Australian dance prodigy who at the age of 5 won a competition that brought him to the attention of the pop singer. California native Safechuck was cast in a Pepsi ad featuring Jackson. The icon begins to fully involve himself in the world of the two boys, staying over at Safechuck’s home, winning over his parents, bringing the Robsons to his secluded Neverland Ranch. The pull of fame is irresistible and the boys are introduced to a world of endless access, wealth and the exhilaration of going on tour. Robson’s mother Joy even decides to split up the family and move with Robson and his sister to Los Angeles to further her son’s dancing career (expecting help from Jackson). But behind all the glitz and fun Safechuck and Robson say they experienced something else, that being sexual abuse by the singer. According to them, Jackson very deviously knew how to lure them away into private moments to take advantage of them physically, all the way into their early teens. They claim it would begin with Jackson wanting them to sleep next to him in bed, before then moving on into abuse. The two would keep the experiences secret from their loved ones for years.

As a document of alleged sexual abuse victims describing their experiences, “Leaving Neverland” is almost unparalleled. For four hours Robson and Safechuck bare themselves before the viewer with a stark, painful frankness. Much of the material will be extremely unnerving and painful for some, as the two provide graphic details of what they allege Jackson did to them while on tour and at Neverland Ranch. Specific acts and locations are described with an unforgettable vividness. Like last year’s HBO film “The Tale,” this is a portrait of what sexual abuse is without a filter. In a sense this is essential, because the camera stays on the two men as they give their descriptions, and there is little denying the pain, emptiness and lingering psychological scars. A quiver in the voice, a sudden glassiness in the eyes, it’s all a bit hard to see as an act (as some of Jackson’s ardent defenders are claiming). The interviews also shape a narrative that serves as a guide for how sexual abuse generates and develops between abuser and victim. The development of trust, the use of gifts for coercion and the imposition of fear are all present. Both men describe Jackson using the language of a tutor, or teacher to initiate sex acts, convincing them it was a physical expression of their bond or love. Sharing their secret would result in them being separated, which was unimaginable for two boys in the presence of their music hero. Reed even uses audio recordings of calls from Jackson to the Safechuck’s home, where the pop star calls him by a nickname (“the little one”) and invites him to see a movie. Jackson’s well-known, infantile attitude is there, but one almost senses something more ominous as well.

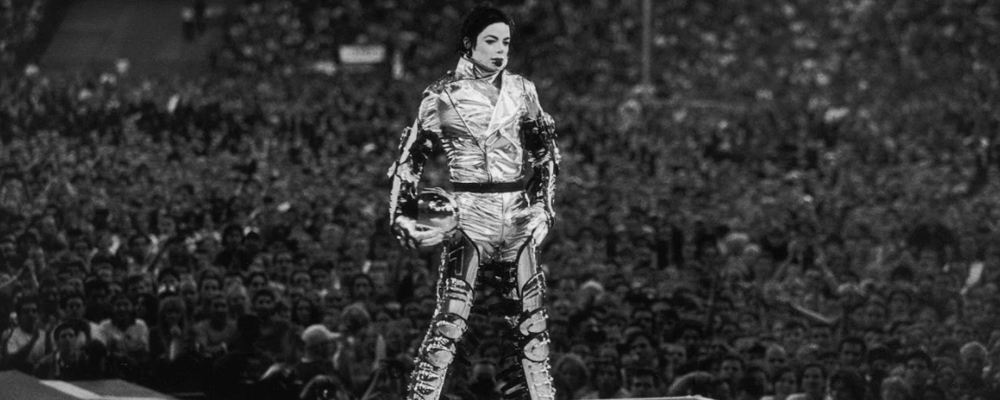

“Leaving Neverland” has already provoked fierce attacks against Safechuck and Robson, and even a lawsuit by Jackson’s estate against HBO, alleging the documentary is pure slander. But what Reed delivers is more complex than a mere attack against a dead celebrity. The portrait that emerges is of a lonely, strange personality, secluded in a fantasy world fueled by immense wealth. Safechuck’s mother shares about feeling an odd, motherly bond with Jackson because he seemed so childlike. He would leave his mansion to stay in their humble house, like a grown man attempting to reclaim some sense of childhood. What makes his alleged crimes more disturbing is how he could have manipulated this perception of innocence to lure in children, who seemed to work as conduits for his twisted sense of sexuality. Of course it’s hard for Jackson’s legions of fans to accept any of thes accusations. There is no denying his astounding talent, the iconic songs, the defining pop image. But one must remember the pop legend that gaves of hits such as “Billie Jean,” “Smooth Criminal” and “Man in the Mirror” was ever so human, and lets not forget that humans can be prone to do selfish, terrible things.

Reed is never seeking to make a biographical piece on Jackson either. The focus is on Safechuck and Robson. The second chapter becomes a harrowing journey of self-discovery for the two. Robson would go on to be a star choreographer for artists like Britney Spears, but would carry with him the painful baggage of his memories with Jackson. In 1993 when the singer was first arrested on molestation charges Robson testified in his favor, still unwilling to turn on who he perceived as a friend. But that wouldn’t be the case when Jackson faced trial again in 2005 (the singer was acquitted). Safechuck would also grapple with his demons as he tried to raise a family as well. The testimonials of the men’s wives, parents and siblings are a cutting reminder of how child sexual abuse leaves a mark with many consequences as victims get older. Robson’s family in particular was deeply affected by Jackson, because it was through meeting him that Robson’s mother decided to leave Australia, including her husband and other son, and chase success for her son in Los Angeles. One senses lingering hate in the voice of Robson’s brother over the whole situation. It’s difficult to not see the painful sincerity in the moments the men describe finally telling their families everything. The reactions of the mothers are also wrenching (Robson’s mother still refuses to hear the details).

Is “Leaving Neverland” bias? Indeed it is. It is true that the other side never gets to speak in this documentary, although one could argue the other side has had most of the media access in the past. Reed is also so focused on his subjects that other avenues are left unexplored. Jackson’s famous marriage to Lisa Marie Presley is a mere footnote with Safechuck saying Jackson described it as a necessary act. But this is a documentary that raises two important points of discussion, one involving the plight of sexual abuse survivors and the other our worship of celebrity. Yes, Jackson left the world a collection of immortal songs when he died in 2009, but that shouldn’t shut the door on discussing his potential faults. Going by what Safechuck and Robson claim, Jackson was able to get away with what he did precisely because of the spell he weaved as a person of power and privilege. It can be painful to accept our idols as human, but it’s essential as our heroes tend to be reflections of the best and worst in us.

“Leaving Neverland” airs in two parts March 3 and 4 at 8 p.m. ET on HBO.