Leonard Cohen Shows Grace in His Final Hour on ‘Thanks for the Dance’

Adi Mehta

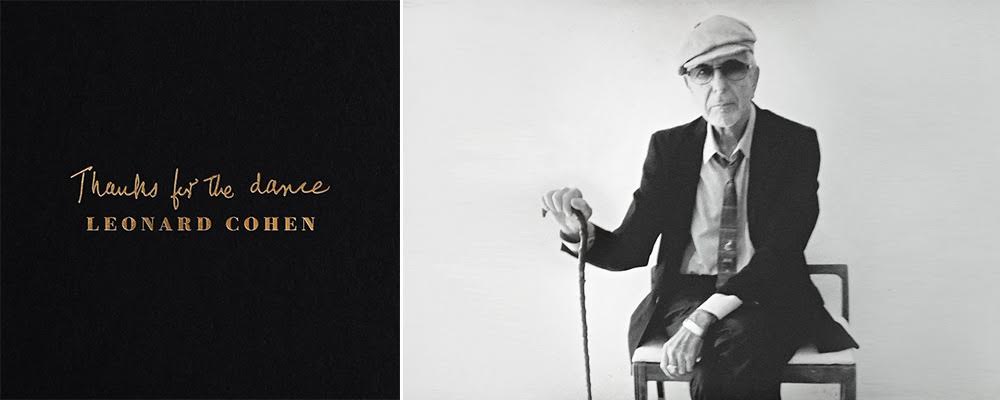

It’s extremely rare for an artist to sense the end coming with adequate time to fully formulate final thoughts and sign off gracefully. Leonard Cohen essentially managed just this, declaring, “I’m leaving the table, I’m out of the game” on “You Want It Darker,” released short of three weeks prior to his death. The album was a measured, comprehensive reflection, but while a satisfying swan song in itself, left the ever fruitful mind behind it with more to say. In foresight, Cohen requested that his son Adam assemble his remaining poetic works from the final sessions. Recorded immobilized, often in an orthopedic medical chair, yet having worked up the energy to don a suit and fedora for good measure, the tracks that form Cohen’s posthumous album “Thanks for the Dance” should not be mistaken for a mere collection of B sides and outtakes. They are thoroughly realized works, lovingly fitted to music mainly by Adam himself, along with contributions from an illustrious cast of musicians including Damien Rice, Beck, Feist, Bryce Dessner of the National, and Richard Reed Parry of Arcade Fire as well as some of Cohen’s favorite songwriting collaborators.

Moments into the opener “Happens to the Heart,” Cohen’s intimate, front-and-center delivery commands attention, and continues to grasp it for the album’s running time. Cohen was always a poet first and foremost, with the tunes and arrangements taking form naturally around his words, and his narrative here, in his distinctive voice, amplifies this quality. When Cohen released 1984’s “Various Positions” after a five year hiatus, his voice had strikingly dropped a minor third, which he attributed to copious whiskey and innumerable cigarettes. Since then, his voice lowered steadily, and now presents itself in a hushed baritone rasp that gives the sound a haunting, theatrical bent. He begins with much reflective reminiscence, but scarcely a trace of the usual sappy regression that typifies such twilight efforts. He recounts trudging along, searching with little avail for meaning in ideology and spirituality, subject to the fate of a fragile romantic. By the second verse, he is already painting vividly with his trademark poetic quirk, mentioning “a mist of summer kisses / Where I tried to double-park.”

Cohen continues, “And the women were in charge… But it left an ugly mark,” which rings true to his life as a “boudoir poet,” as famously described by Joni Mitchell. The said mark has been a feature in Cohen’s work since the days of “So Long Marianne” from his 1967 debut “Songs of Leonard Cohen,” about his lover and muse Marianne Ihlen, who remains a major inspiration on this record. Even now, lines like “Just to look at her was trouble / It was trouble from the start” come across like a reiteration of “And you know that she’s half crazy / But that’s why you want to be there” from that first record’s “Suzanne.” Cohen sings of getting by, with a sense of foreboding slowly creeping in, until “the angel’s got a fiddle / And the devil’s got a harp,” and despair begins to kick in, as one is forced to face the reality of one’s own mortality head-on. There’s a sense of It all having been spelled out from the start, as wide-eyed optimism gives way to worn, nihilistic disillusionment, when Cohen concedes, “I lost my job defending / What happens to the heart.” Still, Cohen is idealistic at his core, maintaining, “We fought for something final / Not the right to disagree,” going on to conclude, “Sure it failed my little fire / But it’s bright, the dying spark.” And so it goes, a spark still standing, a perfect encapsulation of the album at large.

For “Moving On,” Adam Cohen joined forces with veteran songwriter Patrick Leonard, best known for his extensive work with Madonna. A song full of unabashedly doting lyrics, it’s an expression of being in head over heels, and when the fawning gives way to the lamentation “And now you’re gone,” it cuts deep. When Cohen sings, “Who’s moving on, who’s kidding who,” he draws attention to the often tenuous, delusory nature of such euphemism as the titular phrase. The song is a tribute to Marianne Ihlen, who died just four months before Cohen. In his final, touching letter to her during her final bout with cancer, he wrote, “Well Marianne, it’s come to this time when we are really so old and our bodies are falling apart and I think I will follow you very soon.” This track, created around a vocal recorded immediately after Cohen learned of Ilhen’s death, is a natural extension of the pure sentiment.

There are less becoming moments, as on “The Night of Santiago,” which starts out with a wealth of characteristic narrative detail, but startles with occasional egregious lyrics like “her nipples rose like bread.” At any rate, such is the nature of the craft — artistic integrity is a hit-or-miss game, and one that has nearly always worked out in Cohen’s favor. This song benefits greatly from the involvement of guitarist and laud player Javier Mas, who accompanied Cohen on tour since 2008, and plays Cohen’s own guitar on the new album.

The title track was written by Cohen’s former partner Anjani Thomas, originally for her 2006 album “Blue Alert,” but this version is a far more incisive affair. After all the sound and fury, Cohen fondly reflects, in a wounded, crackling voice, “It was hell, it was swell, it was fun.” His counting, “One two three, one two three, one,” has the sound of comfortable surrender, expressed better when he reckons, “The surface is fine / We don’t need to go any deeper.” It’s the idea that no further profundity or meaning is needed, as everything is already perfect as is. The elegantly restrained musical treatment, low in the mix relative to the vocals, gives the feeling of wandering off into distant memories. Upon the chorus, a lilting waltz takes roots, and backing vocals from Feist lift the song into an altogether new plane. Cohen manages to speak volumes in the simplest lyrics like “I was so I / And you were so you,” conjuring the amorous spirit in which all things are amplified, and even the lows are high in memory. Again, the song regards Cohen’s convoluted relationship with Ilhen, in all its triumph and tragedy. The cadence of the music is the perfect conveyance for Cohen’s specific recollections of the pursuals and withdrawals of the titular dance. Well chosen as the title track, “Thanks For the Dance” is the definite centerpiece.

“It’s Torn” was co-written by long-term collaborator Sharon Robinson, who was so integral a force that she appeared alongside Cohen on the cover of his 2001 album “Ten New Songs.” Over a barren, austere arrangement, the abrasive overtones in Cohen’s voice follow an intermittent bassline, as hushed choirs and muted strings slowly envelop him. As with the title track, the music unassumingly captures and enhances the elusive qualities of the lyrics. Instrumentation gets particularly poignant on the following track, “The Goal,” with plaintive piano and rapidly strummed, expressive guitar work from Mas. Over this backdrop, Cohen gently speaks of his perspective at a specific point in life. In final interviews, he spoke of the analgesic value of maintaining order in one’s environment, a topic he explores here with a fatalistic outlook, yet a serene tone. He wrote the lyrics at a time when he claimed to have found his long-term depression suddenly lifted, and we can hear the alleviation in his voice. The climactic lines are “And nothing to teach / Except that the goal / Falls short of the reach,” an inversion of English poet Robert Browning’s “A man’s reach should exceed his grasp,” suggesting optimistically that you have more capacity than what you fixate on.

Cohen was officially ordained a Zen Buddhist monk, and echoes of that persuasion seem to make their way into “Puppets,” in which he makes a case for universal acceptance by likening everyone to a puppet without free will, speaking, “German puppets burned the Jews/ Jewish puppets did not choose… Puppet lovers in their bliss / Turn away from all of this.” Gentle ambiance and ethereal choirs create an atmosphere amid which his musings especially strike as measured words of wisdom. Until this point, Cohen’s vocals have essentially been spoken word performances, and it’s only really on “The Hills” that they ever so slightly approach a melody. They way they skirt around the edges, only hinting at a tune, makes them all the more gratifying, with the gaps filled consummately by the instrumentation and backing vocals, making for a sonic highlight. The song repurposes lyrics from Cohen’s poem ‘Book Of Longing’, previously set to music by Philip Glass on a track named “I Can’t Make The Hills.” The new rendition is the only song on the album for which Cohen wrote the music himself, and it shows. It finds him starkly aware of death’s approach, with lines like ““My page is too white / My ink is too thin / The day wouldn’t write/ What the night pencilled in.” He goes on to personify death as a woman, continuing the femme fatale theme running through his career.

Finally, “Listen to the Hummingbird” fits a recitation from Cohen’s final interview to music. At the time, Cohen expressed worries that he wouldn’t have time to finish the piece, a valid concern considering that he famously took five years to complete “Hallelujah.” Filled with evocative choirs and expressive trills, the final product brings his words effectively to fruition. The lyrics run like an overview of aforementioned ideas. Cohen asserts, “Listen to the hummingbird / Don’t listen to me,” echoing the wise complacence of the title track and the surrender to nature expressed in “Puppets.” He continues, “Listen to the butterfly / Whose days but number three,” reiterating the acknowledgment of mortality explored in “Happens to the Heart” and “The Hills.” Ultimately, he signs off, “Listen to the mind of God / Don’t listen to me.”

Whereas “Want It Darker” was almost categorically bleak, “Thanks For the Dance” finds grace in the darkness without ever descending into the saccharine nostalgic fodder that so often typifies the late undertakings of legends. Posthumous releases are a risky business, and it is a remarkable rarity when one like this comes around. Great care has been taken to fit Cohen’s poetry to music that makes his words resonate. The understated, elegant arrangements serve Cohen’s lyrics well, and the songs form a cohesive set that paint a compelling portrait of the artist in his final hour. The songs are dark, wry, and romantic, capturing all that Cohen is most celebrated for.

“Thanks for the Dance” is available Nov. 22 on Apple Music.