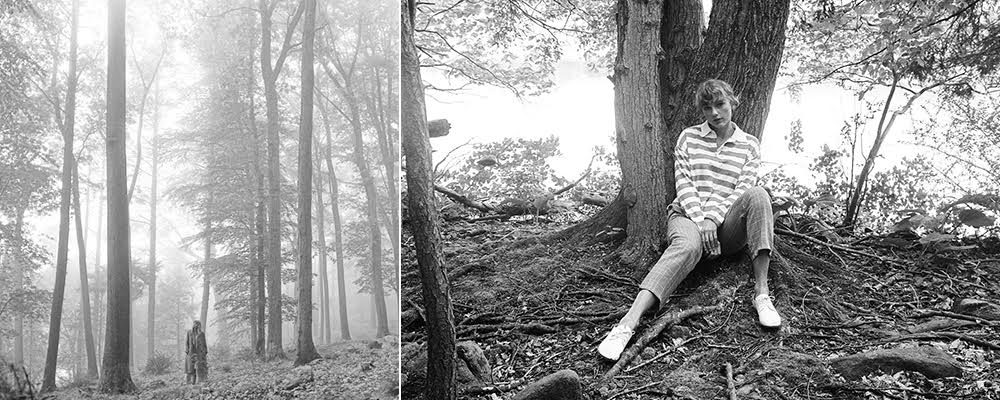

‘Folklore’: Taylor Swift Lets Her Imagination Run Wild and Fleshes Out Her Most Poetic Work Yet

Adi Mehta

As an artist who has always reinvented herself with aplomb, Taylor Swift has turned our current state of social distancing to her advantage by letting her imaginaton run wild and writing from the perspective of other people. She sings in the voice of an infamous socialite who once owned her Rhode Island mansion. She sings of a teenage love triangle, from the perspective of a guy who cheated on a girl, and from the perspective of each girl as well. Along with revisiting her own history, Swift has taken inspiration from other’s stories, and spun these ideas into wealth of folklore, in the form of a her first surprise album. With a new approach, and an elegance to both her lyricism and knack for packing stories into memorable tunes, “Folklore” surpasses all Swift albums that came before it. The quarantine conditions triggered a fortunate recklessness of spirit for Taylor, as her original summer plans of radio promotion and touring were postponed, she threw caution to the wind, and followed her instincts, dropping a release without the traditional album rollout that she is known for, a dramatic change of events from the elaborate promotions that have characterized Swift’s previous releases. She again teamed up with longterm collaborator Jack Antonoff, who has long been an instrumental force in shaping her pop sound. This time, however, Swift also worked with Aaron Dessner, of the National, who steered her sound in a decidedly indie direction. Full of quirky gestures, intricate textures, and ironic lyrics, “Folklore” demonstrates an overall new freedom for Taylor, both lyrically and sonically.

From the first moments of opener “The 1,” Swift sings with a strikingly different tone, one that conveys as much in its inflections and reflective pauses as its wistful lyrics. “Mature” is a descriptor that should always be taken with caution when applied to songwriting, as it’s often a lazy euphemism for lackluster rebounds to conventional forms. In Swift’s case, however, the first taste of her new album is mature, in the best sense of the word, exuding the type of almost blase, resigned composure that an artist only attains after a fruitful career filled with all the highs and lows, trials and tribulations, that eventually settle naturally into a resonant tone of unpretentious wisdom. The song is effortlessly catchy, with an infectious chorus that ends in a climactic couplet of “But it would’ve been fun / If you would’ve been the one.” Musings on past romances and what could have been are a recurrent theme for Swift, surfacing on songs like “I Almost Do” from 2012’s “Red,” but now aching infatuation has evolved into mere retrospective curiosity.

Lead single “Cardigan” begins a triptych of songs exploring a love triangle, one song from each party’s perspective. The speaker on this one is a lady named Betty. Swift sings, “When you are young, they assume you know nothing,” in which one can gauge the wryness, looking back to her 2019 single “Only the Young,” in which she asserted, “Only one thing can save us / Only the young.” When she adoringly envisions someone “Dancin’ in your Levis,” it’s a gentle reminder that this is still the same Taylor Swift who sang, “Think of my head on your chest / And my old faded blue jeans” on her debut single “Tim McGraw.” There’s a type of noir sensibility to the sound that has faint echoes of early Lana del Rey, a rather surprising sound for Swift, but one that she pulls off swimmingly. The chorus Swift fashions out of the titular word is a masterwork that must be heard for full effect, and the song inevitably returns to the topic of lost romances, with Swift reflecting, “I knew you’d miss me once the thrill expired.”

The most drastic departure yet from Swift’s largely autobiographical songwriting comes in “The Last Great American Dynasty,” in which she takes inspiration from Standard Oil heiress Rebekah Harkness, whose Rhode Island mansion Swift bought. By now, we know Swift is not the type to pull punches, and this is another song in an accruing catalogue of cheeky stingers that mock all the snooty critics that have crossed paths with her along the way, with a celebratory zeal. She paints a portrait of a lady who married into aristocracy and ignored the condescension of her stuffy social circle, spinning it into an almost Marie Antoinette-style free revelry. The key line is “She had a marvelous time ruining everything,” sung with plenty of relish, and in the end, adjusted with “She” changed to “I.”

“Exile” was originally sent as a voice memo to Dessner, with Swift singing both male and female parts. When Dessner asked Swift who she would ideally have on male duties, she mentioned Justin Vernon aka Bon Iver, and so we have it. Vernon is quite the versatile vocalist, frequently venturing into all sorts of Auto-tune tomfoolery, but here, he is as candid and authentically emotive as can be, and the song derives much of its evocative power from the simple dynamic between his sonorous, rough-hewn voice tone and Swift’s light, delicate timbre. When they trade lines in the chorus, their interjections sound like passionate entreaties blurted out in vain from two parties that are bonded but skewed. At this point, Swift has developed a persona of a sort of tragic heroine, and when she sings, “I think I’ve seen this film before / So I’m leaving out the side door,” it’s a continuation of the saga that informed songs like 2010’s “If This Was a Movie,” when she pondered, “Come back to me like you would if this was a movie / Baby, what about the ending?”

In Swift’s Netflix documentary “Miss Americana” earlier this year, there was a scene in which Swift brought out her old diaries, and talked about how she actually wrote with a quill for a period. This type of penchant for the quaint romantic sensibilities of yore makes its way into the music, no matter how commercial and accessible the style. On “My Tears Ricochet,” you can hear how much of a natural poet Swift is, alone at the piano, with poignant strings hovering above her, until she finally ascends into a mist of ethereal reverb, as she uses the readily charged setting of a funeral to explore the same themes of lost loves and misdirected infatuations from new angles, with striking lines like “And if I’m dead to you, why are you at the wake?”

“Mirrorball” is sultry and seductive, with Swift singing in a hushed, intimate voice, so that when the chorus line of “Hush” comes along, it’s just a flourish to an idea already communicated. The tragic persona, and the daredevil spark meet halfway as Swift sings, “Hush, I know they said the end is near / But I’m still on my tallest tiptoes.” Swift likens herself to a disco ball, at one hand symbolic of glitz and glamour, but also quick to shatter from the slightest force. And she sings, “And I’ll show you every version of yourself tonight,” in such a way that seems like she said “myself.”

Swift devotes the next song, “Seven,” to a childhood friend, but keeps her lyrics elegantly open ended. She switches from a wailing, imploring verse to a chorus with a swagger and a spring in her step. In the end she sings, “Passed down like folk songs / Our love lasts so long,” which might normally seem like a lazy platitude. In an album this lyrically rich, however, it’s merely a refreshing flash of winsome childlike simplicity. “August” picks up where “Cardigan” left off, with Swift now singing from the point of view of the girl with whom a certain James cheated on the aforementioned Betty. Antonoff was particularly involved in this track, and has named it as his favorite of the album. In a record that leans heavily toward plaintive, slow tunes, this song is refreshingly upbeat, effectively conjuring the idea of the titular heated summer romance. The singsong-ey melody of the chorus seems to mock youthful naivety, as she sprightly sings, “I can see us lost in the memory / August slipped away into a moment in time,” but leaves her final thought suspended and unresolved, as she concludes, “’Cause you were never mine.”

You can certainly hear Antonoff’s signatures as the album develops. The unsparingly confessional “This Is Me Trying” finds Swift cloaked in reverb, with an airy, demure vocal, and slightly ‘80s synth strings, to an end that can sound, somehow, a bit like Angel Olsen. It’s a bold step, just from a sonic standpoint. It’s decidedly indie. “Illicit Affairs” returns to the topic of infidelity, explored before on 2006’s “Should’ve Said No.” The song is a balanced rumination on the pros and cons of the eponymous subject, with a bittersweet tone. Swift sings of “a dwindling, mercurial high,” and “a drug that only worked the first few hundred times.” The song is the most stripped back of the whole lot, with a basic, barebones acoustic guitar backdrop, but Swift compensates for this in intensity, boling up to a rage in the end, asserting, “Don’t call me ‘kid,’ don’t call me ‘baby’ / Look at this idiotic fool that you made me.”

Swift lingers in this sonic space for a bit longer, matching the mellowest acoustic guitar and breezy, effervescent vocals to acerbic lyrics that pack a punch. She throws in little meta snippets that serve as a reminder of her artistic journey, in casual lines like “Bad was the blood of the song in the cab,” but builds to a victory lap of lines in which she cooly reflects, “Cold was the steel of my axe to grind / For the boys who broke my heart / Now I send their babies presents.”

“Mad Woman” serves up the stew that has been brewing steadily since “The Last Great American Dynasty,” when Swift sang about having “a marvelous time ruining everything.” Swift is alone at the piano, and seething, with a tone so hollow and stark that you could slice a knife through with a clean, swift cut. She begins, “What did you think I’d say to that?” Considering how vocal Swift has been about her mistreatment in the musical industry, it’s a fair guess that the action she speaks of is her former label president, Scott Borchetta, selling her masters to Scooter Braun. Braun bought the rights to Swift’s first six studio albums for $300 million, effectively barring Swift from performing her old hits. Swift penned an open letter, explaining, “This is WRONG… Neither of these men had a hand in the writing of those songs. They did nothing to create the relationship I have with my fans.” And it’s hard not to agree with her. Fortunately, she’s fighting back, with millions of fans behind her. The next couple lines are “Does a scorpion sting when fighting back? / They strike to kill, and you know I will.” It just got real.

Swift sings, “No one likes a mad woman,” with the same type of cheeky ironic verve that she did in “The Last Great American Dynasty,” then coyly adds, “You made her like that.” She goes on to throw in a real zinger, noting, “And women like hunting witches too / Doing your dirtiest work for you.” Presumably, this is Swift calling out Braun for hiding from the public eye when she called him out in her open letter, refusing to comment, but having his wife Yael post a lengthy, hostile defense of her husband. And it’s her owning the whole tradition of Salem Witch trials and what not, with a provocative tone and a glimmer in her eye. There are other targets hinted at as well. Just consider Swift’s comment about when “Kim Kardashian orchestrated an illegally recorded snippet of a phone call to be leaked and then Scooter got his two clients together to bully me online about it… Or when his client, Kanye West, organized a revenge porn music video which strips my body naked.”

Seemingly having expelled some demons, Swift switches to almost Enya-level gentleness with “Epiphany.” The song takes inspiration from her grandfather’s experience in the military, and expands it into a broader theme of searching for serenity in a chaotic and violent world. You can hear the contributions of her production team well and clear with another synth-heavy, atmospheric backdrop, and the simplicity of the song is such that every slight waver of Swift’s voice speaks volumes.

At this point, plenty of people might be reasonably wondering who the hell Taylor Swift even is. And just in time, she comes through with a harmonica-laden, twangy tune that will strike a chord with the fans who she won over in the beginning. “Betty” is the final bit of the love triangle, with Swift now singing from the perspective of the boy, James. She takes an overall empathic view of the situation, capturing the silly impulsivity of youth in lines like “I showed up at your party… Will you kiss me on the porch / In front of all your stupid friends?” Little touches like saying “stupid friends” mean volumes. And Swift ties the songs together with touches like a reference to the aforementioned cardigan.

“Peace” combines the bare confessional quality of “This Is Me Trying” with the mature mindset that started the album off with “The 1.” A stripped-down, guitar and vocals song, it’s a track with a simplicity of sentiment that matches the unadorned production. After multitudes of songs about relationships gone awry, it’s an earnest entreaty looking forward with the best of wishes. Finally, “Hoax” rounds things off perfectly, an afterthought, of sorts, and an ending that achieves the perfect balance of sincere sentimentality and steel reserve that define the album altogether. First of all, titling a love song “Hoax” is enough of a statement alone. Swift winds things down over plaintive piano, singing, “Your faithless love’s the only hoax I believe in,” jaded and knowing, but still wide-eyed and romantic.

“Folklore” is a major artistic breakthrough for Taylor Swift, although one could just as well say the same about her last few albums. When she transitioned from broadly country stylings to pop musings, that was one thing. This time, however, Swift’s evolution is far broader and deeper than a stylistic sonic shift. Her songwriting is of an unprecedented calibre. She always had a knack for stringing together memorable tunes from universally relatable, evocative material, with a charming, distinctive delivery. But now she steps up to a higher rank, with a seasoned sensibility, an understated but impressionable showmanship, and a palette that more fully recognizes her musical offerings. You can hear Antonoff’s touches in the pop punch that keeps the album driving, but Aaron Dessner adds a whole new texture that suits Swift brilliantly, trading in a little flash and bombast for some more ruminative explorations. All things considered, if this is Swift’s “indie” album, perhaps she was an indie artist all along — drawing from folk music stylings for her sensibilities, lyrics, and sounds that are too broad to be constrained in any of the other labels often assigned to her. Most of all, Swift’s new lyrical approach, that chooses to also take inspiration from other characters, both real and imagined, rather than solely defaulting to her autobiographical fare, has ushered in a surge of creativity resulting in her most poetic and poignant songs yet.

“Folklore” is available July 24 on Apple Music.