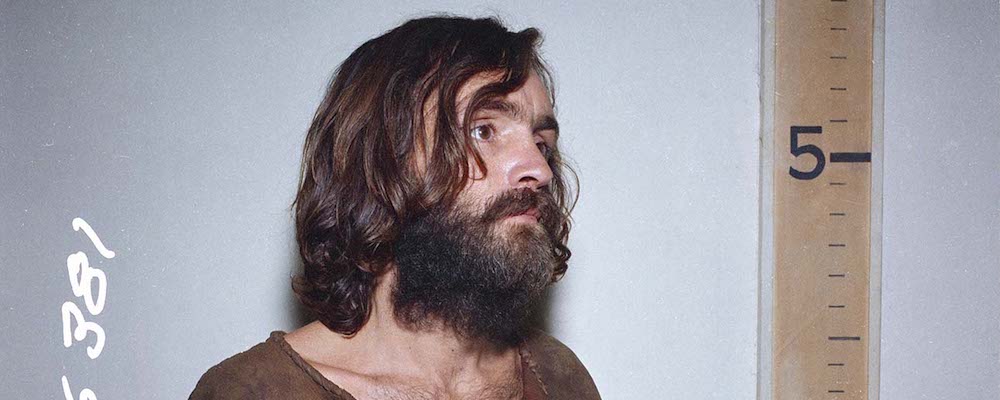

‘Helter Skelter: An American Myth’ Tells Every Detail of the Manson Family

Alci Rengifo

At the end of Epix’s 6-part docuseries, “Helter Skelter: An American Myth,” one question remains: What else can possibly be said about this story? Director Lesley Chilcott has delivered the ultimate docuseries on Charles Manson, his cult, and the infamous murders that made them into dark American icons. Half a century after their crimes, in particular the killing of Sharon Tate, they continue to haunt us. Using rare footage, photographs, fleeting dramatizations, period music, everything except animation, Chilcott tells the whole, disturbing tale. What emerges through its familiar haze of unnerving imagery and bizarre facts is the sad story of Manson himself. Beneath the distorted, poseur mystical rants, Manson was a product of the American underbelly, an outcast in nearly every sense. For Chilcott, this is what should intrigue us more than the morbid impulse to continue turning Manson into some kind of pop artifact. The ‘60s didn’t make Charles Manson. He was a damaged mind that injected himself into the era.

“I came to this with an open mind. Quite frankly, I wasn’t a Manson aficionado, so to speak. There are people that are obsessed with every detail, every family member, every piece of music,” said Chilcott while discussing the making of “Helter Skelter” with Entertainment Voice. “It’s turned into this pop culture phenomenon that I didn’t get. To me, there are so many more important things to be talking about. But I think the crimes were without motive and I think that’s really hard for people to understand. There are plenty of unacceptable crimes that you can say, ‘oh, they did it for this reason.’ These murders don’t have good explanations. When you combine that with this sort of wandering con man, with an acid rap, with a small group of people seeking a leader in leaderless times, he had all the classic cult moves. He renamed the family members, kept them in an isolated ranch, used sex and fear alternately, fed them LSD, did roleplay.”

Before getting deep into Manson and the killings, Chilcott takes the audience back to Los Angeles in the late ‘60s, when the counterculture of the era and Hollywood began to meld. “The murders were committed in the late ‘60s, when Hollywood was supposed to be open. You could pick up Dennis Wilson hitchhiking or he could pick up you. Doors were left unlocked. Although, that’s a bit of a myth, some doors were left locked (laughs). But gates were open and you could crash a party where there was a convict, a movie star, a CEO, all in the same milieu. That has every tantalizing element that makes for a crazy story. Then combine it with this miniature con man, that’s why we’re still talking about it. But I think it’s time to stop.” It would be into this uniquely intermingling world that Manson would wander with his followers, some of whom are still alive and provide commentary in “Helter Skelter.” They all had one thing in common with “Charlie,” their home lives were a wreck. Former Manson Family members, like Catherine Share, give impressively vivid memories of their time roaming with Manson, being seduced by his jargon, finding in him the communal sense they never got in suburban America. He is never portrayed as a criminal mastermind, but as a needy manipulator who took advantage of emotional orphans. It helped that hippie culture was already making the idea of “tuning out,” communes and breaking away from society fashionable. As author Jeff Guinn, who wrote “Manson: The Life and Times of Charles Manson,” states in the docuseries, Manson never believed in any of the ethos of the era. He simply used it for his own selfish aims.

“There are some people that want to talk because they want to atone for their part in it,” said Chilcott, “they feel like it’s their obligation to the murder victims. Bobby Beausoleil called in a number of times, he started talking on the phone. I visited him in prison. He decided he was willing to take us through the murder of Gary Hinman. Even in the trial he gave different reasons for the murder, he didn’t want to be convicted. Years later, through personal work and study, he feels he owes it to Gary Hinman and told us the whole story. We included it. That’s particularly harrowing. Other family members wanted to be used as a cautionary tale. Then there are other family members in the series where it’s been 51 years since they’ve spoken up. They wanted their story out there.”

For viewers well versed in the case, what “Helter Skelter” will offer is a unique visual record. In addition to the stories we’ve heard many times before, like Manson interpreting the Beatles’ “Helter Skelter” as a code for a coming race war, Chilcott compliments it all with extremely rare footage. Manson trying to charm journalists, photos of Beach Boy Dennis Wilson next to the dark guru, nightly news footage of the case never before seen, it all makes for a definitive canvas. “Some documentaries like to use those headlines, ‘never before seen photos!’ But we really do have never seen interviews, audiotapes, news footage that was in a box that was transferred for us by NBC that no one’s ever seen before. You hear Manson a lot too. There are many outtakes from the recordings of his music, where you hear him talking and rambling, so we used the audio from that.” A subtle, recurring theme in the series is how Manson early on displayed a talent for music, but it might have been stunted due to his years without proper guidance, going from reform schools to juvenile detention centers. By the time he forms his “family” and enters recording studios in L.A. (mostly by luring people like Wilson through drugs and girls), he lacks the discipline to properly record. Yet his song “Cease to Exist,” gets ripped off by Wilson and turned into the Beach Boys’ song “Never Learn Not to Love.”

“He was a decent lyricist,” admits Chilcott. “He actually wrote decent song lyrics. He was an ok guitar player. He could put together a tune. But every once in a while he would get it right with a song or two, his voice was decent, his guitar was ok, but it’s the lyrics that make him into some kind of abstract, acid rap poet. I felt a strange sense of relief when I heard a few songs that I liked. It helped me understand why a young woman, or a young man, boys and girls really, would maybe at first fall for him and his story.”

“It was quite something to ask someone, ‘can I have your personal family photos and scan them? Like we did with Manson Family member Diane Lake and some other people,” said Chilcott. “On the victims’ side, the poor victims’ families have to go through this every time someone makes a story about it. The LaBiancas aren’t discussed as much because Sharon Tate was an up and coming movie star, her husband was Roman Polanski. Another victim was a coffee heiress. So some victims are talked about more than others. One of our great finds is the daughter of victim Leno LaBianca. She didn’t want to be on camera, there were also certain things she didn’t want to talk about, but she grew up with this constantly being in her face. I asked if she could give us an audio interview. She gave us some home movies of Leno, so we can see what a great father he was. People always want to talk about the Manson Family, but there are very real victims. I wanted to put these love letters in every episode, so you wouldn’t lose sight of the unspeakable tragedies that actually happened.”

Chilcott gives “Helter Skelter” both a personal and wider touch. We learn about the victims, but Manson is also framed within the context of the times. The radicalism of the ‘60s, the lingering shadow of the Vietnam War, racial tensions in the streets, the emergence of the Black Panthers, all this seems to have swirled into a psychotic stew within Manson’s psyche. When Chilcott mentions that there seems to be no motivation for the crimes that is precisely the impression one gets from looking at the grander picture. Manson’s sole obsession was fame, to achieve being the boss due to a shallow narcissism fueled by years of living on the edges of society. Victims like Tate were history’s targets, pulled into Manson’s path without the slightest clue.

“Manson really, truly, did have a difficult childhood,” emphasizes Chilcott, “his mother went to prison when he was five. She went to this horrific, gothic edifice with 11-foot walls. This thing is scary now and it was scary then. He had to go visit her. She went to prison for a long time for a small robbery. So he was shuffled around. He was famous for making up stories, like claiming he was sold for a pitcher of beer, but there were stories bad enough that he didn’t have to make them up.”

By the final episode, when Manson and his followers meet their day in court, which came with its own, at times eerie antics, “Helter Skelter” has given us a grand, human tragedy. We may never know exactly why Manson ordered his followers to commit butchery, but do broken minds ever make much sense? Instead the story endures in mythic stature as the hangover after the Summer of Love.

“I think the part of the story that speaks to us now is it’s very easy to say I would never fall for a cult leader or a ‘guru,’ as they would say in the ‘60s. But the classic moves I’ve mentioned before, the renaming of people, isolating them, making them do things that would make them beholden to him…it’s easy to say that wouldn’t happen to me. Yet, we see victims of modern-day cults. Any time you give up a part of yourself and keep following someone who keeps repeating and repeating phrases over and over, that are not true, eventually you will put your trust in them. That’s very relevant now,” said Chilcott. However, the director believes Manson’s time has passed as a figure of endless pop cultural elevation. “I will say this: this story does not deserve historical relevance. Charlie was a small con artist who was small in every way. His family members were puppets and we’re puppets of the media, of his story. He would keep dangling things in front of our eyes, like having outrageous parole hearings, doing the interview with Geraldo, right up until his death in 2017. We should take the warning signs from this cult, learn from it, and move on to more important things.”

“Helter Skelter: An American Myth” premieres July 26 and airs Sundays at 8 pm ET on Epix.