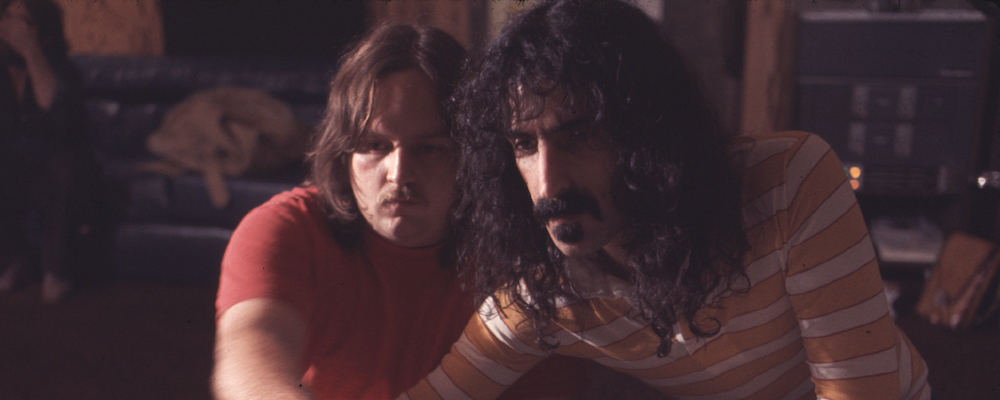

Frank Zappa Documentary Profiles in Rich Detail the Life and Times of a Rock Icon

Alci Rengifo

Frank Zappa was one of those artists who truly meant it when he said he didn’t want to play by the rules. “Zappa” chronicles in minute detail the life of the iconic musician, who basked in defying every norm in any setting. He could never fit in with the conservatives, while at the same time refusing to take on the drugged out persona of a ‘60s Flower Child. Zappa never cared much for making hits and his one chart topper came about almost by accident. Director Alex Winter crafts a portrait of Zappa that avoids feeling like a standard rock biography. It’s the in-depth exploration of a personality. Zappa defined independence, but that could also come with its own pitfalls, not least a difficult personality.

Winter opens the documentary in 1989, when Zappa was invited to perform in what used to be Czechoslovakia during the Velvet Revolution. He tells the masses to not make their country a copy of anyone else. It’s a fitting opener considering this would be Zappa’s very ethos. We then cut back to the 1950s as Zappa in interviews discusses his early love of film as a kid in Baltimore, Maryland. Film editing was an early passion and Winter includes rare family home movies Zappa put together with his siblings. A voracious autodidact, Zappa would soon teach himself music and guitar, with a particular love for Edgar Varese, a composer known for his experimental (if not controversial) use of sound. A whole mixture of influences, from classical to blues, would first lead Zappa to try out film scoring. But an ill-fated hire by a stag film company would land him in jail. Zappa packed his bags and left for Los Angeles, where the ‘60s counterculture was blossoming into radical new sounds and art forms. It seemed like the perfect place for Zappa’s emerging style. He formed the band the Mothers of Invention to finally have a working unit to write and tour with. Yet he would have to find new homes, new places, to make sounds unlike anything else in the rock realm, even as his fame and status gradually grew and would pull in major icons of the era.

As a work of cultural history, “Zappa” is fascinating by the angle it takes in looking at ‘60s music from a fresh angle. In a way Frank Zappa was the avant-garde of ‘60s rock. His approach to composition was about ambiance and tone, mixing sounds and instruments like splashes of color. The two albums that first made Mothers of Invention renowned, “Freak Out” and “We’re only in it for the Money,” feature tracks where rock and symphonic melodies meld into exciting music that refuses to become Top 40-friendly. While Zappa definitely drank from the spirit of the times, adopting the long-haired style that defined youthful rebellion, he never spoke or saw himself in the same rock terms as Jim Morrison or Jimi Hendrix. In his mind he was always a composer, more Philip Glass than John Lennon. Although the greats of the times, like Lennon and Mick Jagger would flock to Laurel Canyon to meet him. His late wife Gail chimes in saying she always saw herself as the wife of a composer before anything else. In his interviews and commentaries, Zappa does come across as a more refined sort of auteur, to the point of getting too distant or even pretentious. He dismisses the need for drugs and in 1978 Saturday Night Live would invite him to host, with skits making fun of his anti-toking ways. He didn’t refrain from the sexual revolution and in his late ’60s heyday practiced an open marriage with Gail.

Refreshingly, however, “Zappa” doesn’t try to fill in space by lingering too long on music numbers or recording sessions. Winter is sincerely interested in Zappa as a person. He prefers to focus on the clips where Zappa and those who knew him talk about his characteristics. Like all humans he was complex and full of contradictions. His music was expressive yet he could be cold towards collaborators. One band member recalls Zappa only shook his hand once in the span of a decade. He was a workaholic who grew so tired of catering to the need of a constant unit he disbanded the Mothers of Invention’s original lineup to turn the project into a revolving door of musicians. Even in his interviews Zappa can be rather stern, proclaiming he records music so he can listen to it himself at home, and if anyone else wants to join in by purchasing the record then good for them. This defiant independence becomes the central theme of “Zappa.” While he was more business conscious than many of his peers, including The Beatles, Zappa was also the least commercially-driven. He recorded with the London Symphony Orchestra because he wanted to and admits he paid for such projects out of his own pocket without any hope of commercial success. In 1982 his biggest chart topper, “Valley Girl,” was the result of his daughter, Moon Unit, wanting to spend more time with him. Zappa confesses he was touring in Italy when the song hit the chart and he knew nothing of its initial success. While speaking at a university, Zappa scoffs at the notion of music studies and recommends aspiring, original musicians get a real estate license. Yet more contradictions considering Zappa would start his own record label in the ‘70s which helped underdogs like Alice Cooper get their first big breaks.

With energetic editing and a seamless flow of footage, Winter creates such a detailed portrait of Zappa that there should never be a need for a biopic drama of the man. Although you wonder if Zappa would even want that. In one of his life’s great ironies, he became a major voice in the late ‘80s against the movement to put parental advisory labels on albums. But he’s left standing alone with few major artists joining the cause. The anti-commercialist stood for defending the freedom of commercial art. He became so vocal, in fact, that reportedly the post-Soviet Czech government of Václav Havel was warned to keep its distance lest it wanted to risk U.S. cooperation. In a way Zappa was a true rebel in all these regards. He refused to make music to conform to popular taste and when he truly felt passionate about a public issue he would take a full stand. He took his freedom seriously.

Prostate cancer would eventually take Zappa away in 1993. Winter’s documentary may help revive some of his work for fresh listeners. Maybe now, in this era of all styles and endless supply of different music via streaming, the time is ripe for Zappa’s work to have a strong renaissance. If art is a reflection of the artist, then “Zappa” makes clear how Frank Zappa’s very personality can be found in his albums. He was disciplined in honing his craft but bold in its practice. This is precisely the kind of documentary he deserves, well-crafted yet unconventional. Whether you respond to his music or not, it cannot be denied Frank Zappa could have been the eternal poster child for the idea of being yourself.

“Zappa” releases Nov. 27 on VOD.