‘Biggie: I Got a Story to Tell’ Skims Over the Notorious B.I.G.’s Life With New Footage and Insightful Commentary

Alci Rengifo

The new Netflix documentary “Biggie: I Got a Story to Tell” is a perfect introduction for viewers who know next to nothing about Notorious B.I.G., born Christopher George Latore Wallace. The question is how many viewers who stream this efficiently-made, at times emotive documentary, don’t already know the basic details? The story of Wallace, still affectionately known as Biggie, is firmly a part of hip-hop and general popular music mythology. His killing in 1997 remains unsolved and forever debated. Wallace’s rise from Brooklyn to the forefront of the major shift in hip-hop at the dawn of the ‘90s, when old rap forms were shoved aside by the slick grit of gangsta rap, is looked over with a brisk pace here. It’s an energetic overview.

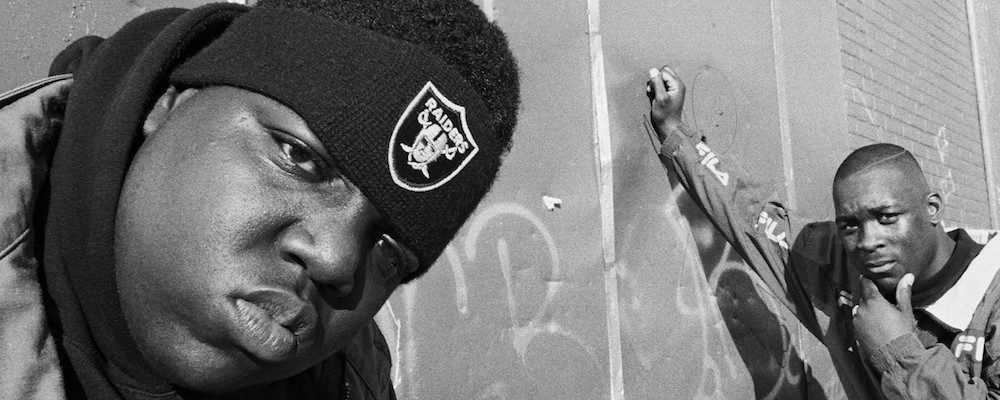

What director Emmett Malloy utilizes to give “Biggie” a fresh feel is a focus on previously unseen camcorder footage shot by Damien “D-Roc” Butler, who was that guy in any superstar’s entourage filming the whole experience. It makes perfect sense, because for Wallace and his collaborators, there was a dreamlike quality to being catapulted to the heights of popular culture. The footage itself reveals nothing extreme or controversial. What we do get is a friendlier, even sweeter side to the man that could easily get lost in the public image of the street smart rapper pulling himself up through ferocious talent, after a life of dealing crack in the streets of Brooklyn. It’s those early years that get the most emphasis in the narrative. Wallace’s mother, Voletta Wallace, tells her own story of being an immigrant from Jamaica in the late ‘60s, seeking a life beyond her rural upbringing. Wallace’s friends remember her as a great parent but having to work all day, leaving Wallace to find his way around the streets of a pre-gentrified New York City. The streets would form Wallace in many ways, first as the arena where the crack hustle gave him a first taste of money but also danger and despair. Rap was his passion, emboldened by summer trips to Jamaica where his uncle would introduce him to the Jamaican DJ scene. Wallace would bring that influence back to a Brooklyn where urban inequality would lead many young Black Americans to try drug dealing. With his astounding talent, friends would see in Wallace a symbol that it was possible to leave it behind through a combination of dreaming and determination.

These snippets of Wallace’s early biography prove to be some of the more intriguing moments in “Biggie” only because they rarely get much in-depth coverage. The rest of the documentary essentially recaps in quick succession the rest of the Biggie myth. It’s never a boring story to tell and there’s still a great exhilaration to those early videos of Wallace free styling and battling with fellow rappers in the street. Donald Harrison, a jazz musician who was Wallace’s neighbor details how Wallace’s flow was influenced by the snap and rhythm of jazz drumming. Sean “P.Diddy” Combs is back to recount his legendary partnership with Wallace. When not giving his usual talking points, he also delves into how Wallace was heavily influenced by R&B, which gave his cadence a unique style that stood apart from the usual rap sound of the ‘80s. Juxtaposed is Butler’s footage of the early, pre-fame days when Wallace had signed with Diddy’s original record label and spent the days with his posse, the Junior Mafia, performing to packed venues but wondering if real success would ever come. A great bit of footage takes us inside a scorching tour bus where Wallace and his posse are melting from lack of air conditioning, resorting to pouring bottles of water on themselves to survive.

Success would eventually arrive massively as the gangsta rap genre would define the industry in a decade where Wallace would share the pedestal with that other icon, Tupac Shakur. It’s astounding to realize Wallace’s legend stems from only two full-length albums, “Ready to Die” and “Life After the Death,” the latter released posthumously. Malloy and the interview subjects briefly touch on the period, including the bizarre “East Coast-West Coast feud” that developed between factions who took Wallace and Shakur as their representatives, including their respective labels Bad Boy Records and Death Row Records. To this day Diddy looks astounded over what took place, and the documentary never goes deeper to probe how gang warfare infiltrated an industry. In 1996 Tupac was mysteriously shot at a New York recording studio, and for whatever reason he blamed Wallace. Their once close friendship was shattered and the feud would spiral out of control. Tupac would be shot down in Las Vegas in 1996, a crime that also remains unsolved. Curiously, Malloy leaves out any mention of infamous Death Row records head honcho Suge Knight, long suspected of being connected to both the Tupac and Wallace shootings. But for that darker area of this story there are other documentaries like Nick Broomfield’s gonzo-style “Biggie & Tupac.” Commentary by Wallace’s widow, singer Faith Evans, is also surprisingly sparse. Considering Wallace has already inspired at least one biopic, 2009’s “Notorious,” maybe Malloy feels there’s no need to give every aspect of his subject’s life wide space.

The dominant subject in “Biggie” turns out to be Voletta Wallace. Through her we get a real sense of the triumph and tragedy of her son. She shares endearing anecdotes about being rattled by the profanity in his lyrics, and there are also funny but rather dark memories from friends about her mistaking his crack stash for dried potato chunks. Voletta deserves a film of her own. The rest of the documentary is immersive in its filmic style, which is reminiscent of Malloy’s work in great concert films like “The White Stripes Under Great White Northern Lights.” He builds an emotional rhythm with the editing and mixes the sounds of Wallace’s music with an emotive orchestral score by Adam Peters. He opens and closes with the funeral procession for Wallace, following his 1997 murder in Los Angeles, which is also quickly passed over without much detail. The result is not a revelatory look at Wallace, but a portrait of a great talent. It’s a reminder of who he was and through the new video clips, a reminder that human stories are always taking place behind the public image. In a sense his lyrics about life on the streets, with all of its uncertainty, violence and hopes, grit and tragedy, tell the story better. The worth of “Biggie” is that it might spark curiosity in a viewer just barely discovering his music — hopefully it will inspire them to seek more.

“Biggie: I Got a Story to Tell” begins streaming March 1 on Netflix.