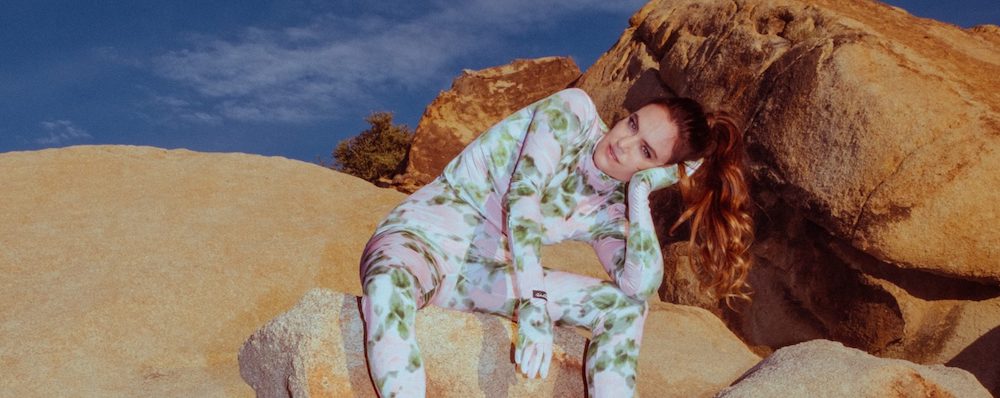

Julia Stone on Reclaiming Her Lost Year of Dancing With ‘Sixty Summers’

Todd Gilchrist

Julia Stone is a multi-instrumentalist and folk singer by trade, but you wouldn’t know that from listening to her new album “Sixty Summers.” Co-produced by Thomas “Doveman” Bartlett and Annie “St. Vincent” Clark, the record takes a sharp departure from the sound that has defined her for much of her career, not necessarily capitulating to market trends but featuring a fun, adventuresome, deeply danceable sound that any rising pop star would kill to call her or his own. Working with Bartlett and Clark, Stone simultaneously ventured outside her comfort zone and sharpened her skills as a songwriter and balladeer like never before — a meeting of minds and bridging of sensibilities that came together over four long years to deliver an incredibly strong collection of songs.

Stone recently spoke to Entertainment Voice about the process of creating this record, and how it was meant for a fun-filled tour that a year of disasters and tragedies inevitably postponed. Discussing how she relied upon her collaborators’ encyclopedic knowledge of music to challenge expectations and push her creativity, Stone not only looked back at the four years of recording (and another two since its completion) that transformed her as an artist and forced her to grow, but contemplated where she’s at, and where she wants to go now that the album is finally being released into the world, exactly at a moment when her fans are beginning to rediscover the shared experiences she tried to capture with this exuberant, eclectic music.

I read that this album was recorded between 2015 and 2019. Is that an average amount of time for you, or similar to experiences you’ve had in the past?

It’s pretty different to anything that I’ve made in the past, because at the time I was making it with my brother, we were touring our fourth record — maybe even our third record and fourth record. I was touring probably eight months of the year, and then I’d go home, see the family and then come to New York and hang out with Thomas [Bartlett] for a few weeks at a time. So even though it was written over that period of time, it wasn’t working on a record for that long. It was just little pockets of time, and writing in a different way. I wasn’t writing to make a record, I was writing for the fun of it. I love music so much that after being on tour, the thing that I wanted to do with my time off was to write more music. I kept thinking, let’s just keep writing because we’re having a good time. And then 2019 was when Thomas said to me, we’ve got about 30 songs now, do you want to do something with them? And he said, it seems that you and I together can’t really decide what to do, we just keep on writing more songs. Why don’t we see if Annie [Clark] wants to come in and produce it and tell us what the record is. And she came on board and helped refine it and turn it into a cohesive twelve tracks or thirteen tracks or whatever it is.

Your Wikipedia entry describes you as like a “folk artist,” so a dance-oriented album from you is very surprising. How readily did that different direction emerge and what led you towards that?

I’ve grown up listening to a lot of music that was more rhythmic than the music that I was making with my brother. Songwriting is something that has always interested me, and because I write mostly on the guitar and on the piano, I think sometimes the instrument that you write on dictates the sound that the song goes in. You can hear that with people who do cover songs of other people’s music — you can change a song that’s an electronic song into a folk song or a folk song into an electronic song based on how you produce it. When I started working with Thomas, I was writing to beats and synths, and I was writing to different sounds. And songs like “Break” and “Unreal” were already quite formed before I even started writing melodies and lyrics, so that brought out a different way of writing; I’d turn up at the studio and Thomas is always making tracks. I remember him playing “Break,” and I just went, “put on a microphone. I want to say some stuff.” And I started dancing and I was singing all of this stuff, and we just kept recording for 20 minutes and then edited it down. So a song like “Break” was really all ready when we wrote it. But something like “Who” started off as more of a piano song, more of a ballad-y feeling, and Annie was like, no, I want to hear this as a dance track. So it was a bit of a mix, but a lot of the songs were already in the writing process sounding pretty different to anything I’d written before.

“Break” reminds me very much of Bjork, maybe if she teamed up with Bonde de Role. And you shuffle in this really interesting way through a number of genres or sounds on this record. Were there signposts or references that helped you sort of zero in on any of these songs or to give you some inspiration or direction?

Over the years having worked with different producers, that’s something that I’ve always admired about other people, but it’s not a quality that I particularly have in my songwriting or my writing. We grew up in a household where there was a lot of live music happening in the house because my dad’s band was always rehearsing in the house. My dad’s band was a party band, so they would play at weddings and parties and they were playing anything from Creedence Clearwater to the Beatles to Blues Brothers soundtrack stuff. So there’s certainly some records I remember, but I very rarely listen to music when I’m writing. But Annie and Thomas have such an incredible wealth of knowledge about music from all different times, different bands. And particularly, I noticed with Annie, and also something that I thought was pretty impressive because my brother and I worked with Rick Rubin on our third record and something that I remember thinking about Rick that was really amazing was the catalog in his brain of different records from different times, different songs. And he would bring up a song that was pretty obscure and just play it for us before we’d do a take, and the song wouldn’t necessarily be in the same genre even, but it would be an inspiration that would point us in a direction in terms of a feeling. And he did that quite often, where he’d play a track and then he’d go, “okay, now go and do a take.” And Annie did a similar thing. I remember thinking it was really cool as a producer, a really cool technique, because she’d throw on something and say something about, I don’t know, some band out of Manchester who put out one record in 1994, and track 12 off the record had this really cool bass part — let’s just have a quick listen to it. And she was doing that all the time, just pulling up a song, and saying, “this song reminds me of something in this feeling that you’re going for.” I was always just incredibly impressed by how deep her musical knowledge was and how she could draw on that to utilize it as inspiration in the process. But I don’t have the brain for that. Annie and Thomas are much more capable of using that in the process. I certainly can hear what everybody says when they’re saying there’s like a little bit of Talking Heads vibe, or there’s Serge Gainsbourg on “Dance.” And, obviously it’s really nice to ever be in the same sentence and be compared to people who have written extraordinary music. But it’s not a talent I have at all.

Annie is such a gifted songwriter and producer in terms of finding the right balance of something that has that pop edge, but also in adding these idiosyncrasies to it. As you were venturing more into a pop sphere, is there anything that you wanted to explore specifically, or maybe to avoid?

What I liked about making the record was when we were getting towards the end, we couldn’t place what it was, and I felt excited by that. Like you said before, the songs have a lot of different feelings about them, and it did feel like every song had its own mood and its own space. And I think we were a bit like, well, what is this? And I think the ‘what is this’ felt exciting, you know? I’ve been in a style and a genre with my brother for many years, and it felt exciting that I didn’t know what kind of record it was going to be — where it was going to sit in the world and who was going to enjoy it. And certainly there’s a particular type of music that people would expect from me. And then here was this thing that I didn’t even know how to explain. And I think one of the things I really wanted out of the making of the record, I was having a lot of fun writing the music, and collaborating with Annie and Thomas, with Bryce, with Matt, with Stella, with Sam and everybody who came in and worked on it. It was really fun, and I really wanted to keep pushing the music towards being fun to play, so that it would be a fun show to perform. Obviously we finished this pre-pandemic, so I was looking forward to being on stage and playing the songs and having music that myself and the band and the audience could dance to. I was hoping that the record would predominantly stay in the world of movement and grooves and rhythms that felt like there was a constant opportunity to move your body. And then Annie, at the helm of the final stages of production, she really also brought out the importance of every lyric having a deeper meaning. She’s very adamant about “tell me what it means. Can you say it better? Is there a better way to say what you’re trying to say?” And that was really exciting for me as a songwriter to not get away with any lazy songwriting or any lazy choices. Everything had to mean something and I had to explain it to her and if I couldn’t explain it, I bloody well better figure out how to.

To that end, as a songwriter how literal do you feel like your songs either typically are, or did they become, through the course of recording this? Do you consistently have either a point of view or preference in that way?

I think probably historically I’ve been a bit more abstract as a songwriter, but I really appreciate lyrics that let you know where you are and where you’re heading. I think I’ve found a nice middle ground where on this record, there are some songs that are very direct, like “We All Have” — it’s a very straightforward song about just relaxing because everything changes and all we need to be here for is love and everything shifts in time. And then songs like “Break,” which are a little bit more abstract, that has a rambling spoken word feeling of just the manic-ness of falling in love and being taken on that journey and not being able to stop that and be at the mercy of somebody else’s power over you, or being drawn into that. And it really goes back and forwards in some songs. “Substance” Is a great example of a song that’s very storytelling, takes you through what’s happened in being with somebody who doesn’t introduce you to their friends at a party, but will come and stay the night. So I enjoy both types of writing, but on this record, I think I have found for me a good balance of the two and the two sides of how I like to hear music.

Was there a track on this record that became sort of the linchpin for the album or that gave you a sense of confidence that you were going in the right direction?

I think for me, that was “Unreal.” “Unreal” was a song that I wrote as a love song for Thomas, because I was finding so much comfort in being in New York, being in that studio over the years, and taking breaks from touring life. When the tour was over, I didn’t have a real sense of solid grounding, and Thomas and the studio became that for me. And when I wrote “Unreal,” I wanted him to hear a song that reflected how I felt about that space and that time. And it was really immediate to me, that song, that I was like, Oh, this is something I’d like to put out in the world. And I hadn’t felt compelled at any stage to put the songs out. I was just enjoying writing the music. And “Unreal” was the song that I felt like once it was in a good place, I was proud to show people. And that’s always an indicator for me that I’m into what I’m doing, when I’m forcing other people to listen to it (laughs).

Well, how did the experiences of the last year change your perspective on the idea of releasing an album that you wanted to be fun to play and a fun experience for audiences to hear? Has the last year of not having the opportunity to perform it given you a sense of catharsis for finally having released it, or does it make you consider making more music like this to build it out further?

It’s a really good question. I honestly don’t know where I’ve landed in terms of answering that cohesively, but I would say from where I stand right now with it coming out in a few weeks and having had such a big lead up because of the pandemic ultimately and having had a completely different vision for how I would introduce this music into the world and having to adapt to that I think initially there were a lot of things that just made me think this isn’t the right time to put this music out which was the record was finished probably early 2020, and we had the bushfires in Australia and I wanted to contribute to that. And, that was the Songs for Australia record, which was the front end of 2020. I spent time investing in making that and working with everybody to do something. And, then it was a bunch of months just realizing that we weren’t going anywhere and everything changing and figuring out, well, “what do I do with this now?” Because it is a record about celebration and dancing. And then I think I came to a point in the year before we put out “Break,” it felt like it would be nice to put some color into the space. And that was the point of feeling like it doesn’t matter that I can’t play it live. It doesn’t matter that I can’t share it in the way that I had envisioned. I just want to share it. And so that was the beginning of really starting to get excited about how to present it visually in what essentially is an online world — and that was music videos and single artwork and collaborating with people from a distance. And how do you do that when you’re in Stage Four lockdown in Melbourne, Australia and we just got really creative and that was another way for me to feel that I could offer something in a space that was challenging. And it was helpful, I think, for me personally, just to reframe, instead of feeling like, Oh, it doesn’t fit. It was like, it can fit. I just have to adapt. And so we got to do some incredible things during the pandemic, doing a video with Susan and Denny, mid-Covid shooting with people in their seventies in New York City and making sure that was safe and worked. And then people’s passion to still want to tell stories is just endlessly inspiring. We were all working so hard to continue to make art in the midst of it all. So, I guess moving forward, your question is, “do I think about making another body of work that keeps me in this realm and helps to support the world I’d built?” I honestly don’t know. I guess I just can’t wait for it to be out in the world. Luckily in Australia we are able to play concerts and I’ve heard that America is starting to talk about putting on shows. I don’t know how accurate any of this is, but my hope is that by the back end of this year or in early 2022, I can actually really perform a show.

In Los Angeles, they’ve started talking about opening up venues, so that would be very exciting for artists, and for audiences for that matter.

I mean, it takes a minute. Like I went out dancing on the weekend in Australia, in Melbourne. And it’s the first time I’d been out to a club and everybody’s close to each other and dancing and there’s a certain amount of, like, it feels weird at first. But I think humans, once we know that we’re safe or even that we’re, you know, mostly safe, everybody wants that and everybody wants that connection. So I think it’ll take a minute in America, but here we’re in pretty good shape, but it’ll probably take a minute for audiences to feel comfortable in that environment again. But once you feel comfy, you’re straight back there.

“Sixty Summers” releases April 23 on Apple Music.