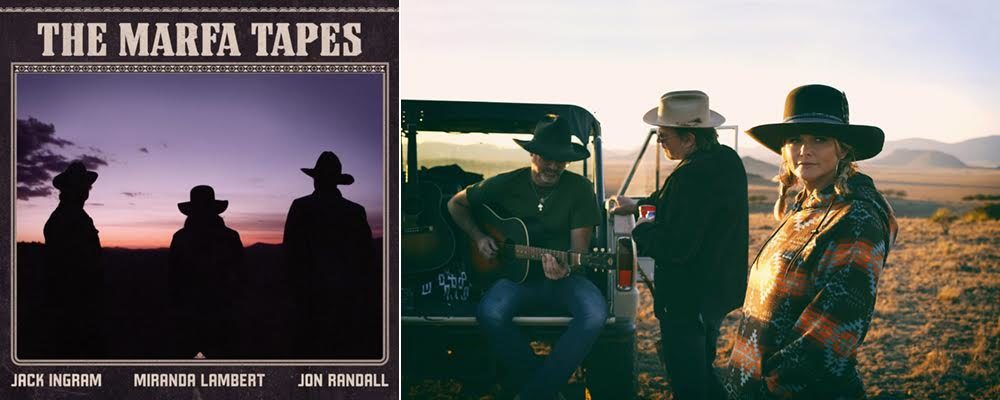

Miranda Lambert Teams With Jack Ingram and Jon Randall for Intimate, Unvarnished ‘The Marfa Tapes’

Todd Gilchrist

Among a growing collection of releases either commemorating the quarantine or reflecting it, “The Marfa Tapes” carries an imprint not only more authentic than most, but more likely to endure. Miranda Lambert, sitting down with Jack Ingram and Jon Randall in Texas’ artist enclave of Marfa, has recorded the modern equivalent of a record of campfire songs, complete with crackling embers and the ambience of a sky full of stars. That Lambert delightfully includes a few of her own gaffes, including stumbled melodies and forgotten lyrics, makes the record feel additionally organic — more than a jam session, less than a studio album; but “The Marfa Tapes” as much provides a soundtrack to listeners’ own low-key hangouts as it feels like one with these talented musicians.

Lambert takes the lead on “In His Arms,” setting the tone for the album with a wistful guitar ballad about a Juarez cowboy she once danced with “on a straight tequila high,” and wondering where he is now. Ingram and Randall join in for chorus harmonies, complementing one another in the lead-in to the next song, “I Don’t Like It.” What immediately resonates is not just the absolutely gorgeous songwriting, amplified by Lambert’s lead vocal, but also the openness and sincerity of the recording process, unencumbered by expectations of perfection, and possibly even of anyone but them ever hearing the songs. These aren’t complicated songs — they simply and earnestly confess love and longing while reflecting on life — but the poetry the trio uses to express some familiar sentiments gives them a depth and relatability, whether you’re a fan of their more elaborately produced material or not.

Moreover, the songs are grown up: broken relationships are a country music staple, but touches like “Kids and time will learn to love us both / We both hate to see it end” in the lyrics of “The Wind’s Just Gonna Blow” point to more sophisticated and practical concerns, while still being paired with the poetry of lines like “Your halo’s in the dresser drawer / And I don’t wear my ring no more.” Similarly, lovestruck highwaymen have a canon all to themselves, but on “Am I Right Or Amarillo,” they capture both the sensibility and the lifestyle with an deft specificity: “It’s too late to stop drinking / Too early to go home / There’s a flashing vacancy sign / Just across the road.”

In country music’s well-established repertoire, getting away from an unhappy relationship can frequently take the form of revenge or melodrama. But “Waxahachie” offers an oblique narrative about what its protagonist is getting away from (“Nobody ever left New Orleans as mad as I was / I wrote a lipstick letter on the mirror with a bourbon buzz”), and then pivots to the solace provided by an old friend, a decidedly healthier approach to heartbreak, dotted with future potential without necessary signaling romantic inevitability (“It’s comin’ on 4 am / I need to be in your arms again”). They shift into a more playful mood on “Homegrown Tomatoes,” a song about, and written for, good food, drink and especially good trouble (“Come on Guy, get us all high, sing us a country song / All fucked up, fallin’ in love, everybody’s singing along”), joking afterward about its meaning even if the answer is obvious from the song’s bouncy, carefree melodies.

There’s a tender sensitivity to “Breaking A Heart,” as they wrestle with which is tougher at the end of a relationship, being hurt or hurting someone else, but “Ghost” foregrounds Lambert again as she personifies a cathartic half of that equation, starting with a purge (“I burned your Levi’s and your pearl snap shirts / Ashes to ashes and dirt to dirt”) before announcing her liberation (“My spirit’s high, so don’t you hang around / Silver tongued devil, you can’t hold me down”). Next, “Geraldine” echoes a country music all-timer, Dolly Parton’s “Jolene” (even referencing the song’s mythic other woman), except this time, Lambert’s musical alter ego is unafraid of her competition, proclaiming, “You got ‘em all on their knees / But you can’t take a man from me.” The lazy-day, mutually-unrequited romance of “We’ll Always Have The Blues” offers a lovely opportunity to exhale, as Ingram sings about a moment of two people being together but knowing they have to end the night apart: “It’s only for tonight / It’s almost closing time / Maybe one more dance or two / We can’t have each other / But we’ll always have the blues.”

“Tin Man” uses “The Wizard of Oz”’s endlessly sentimental hero to point out how tough it is when you actually have to go through all the emotions that come with a heart, before “Two-Step Down To Texas” pitches a rousing night on a Texas town, as all three musicians laugh and carry on in between harmonies. With Ingram on lead vocal, “Anchor” offers end of the world love before Lambert stumbles over the lyrics of her own “Tequila Does,” producing laughs from her collaborators during this tribute to the irresistible, not-so-sweet libation of the liquor in its title. And finally, they sort of sum up their experience, and ours, with “Amazing Grace (West Texas),” a rhapsodic depiction of a physical landscape, a romantic relationship, and the little details and memories that connect them to one another, especially if you’ve experienced any of them in the Lone Star State. Across these 15 tracks, Lambert and her collaborators find solace, and offer it to their listeners, with a rich combination of poetry and unvarnished truth, so much so that “The Marfa Tapes” seems too intimate to qualify as a formal album; but when it’s finished you feel like you were there, and in contrast to too many records over the last year about being stuck in one place, getting the opportunity to occupy a new and different space — even if it’s just the recesses of their creativity — is a special thing.

“The Marfa Tapes” releases May 7 on Apple Music.