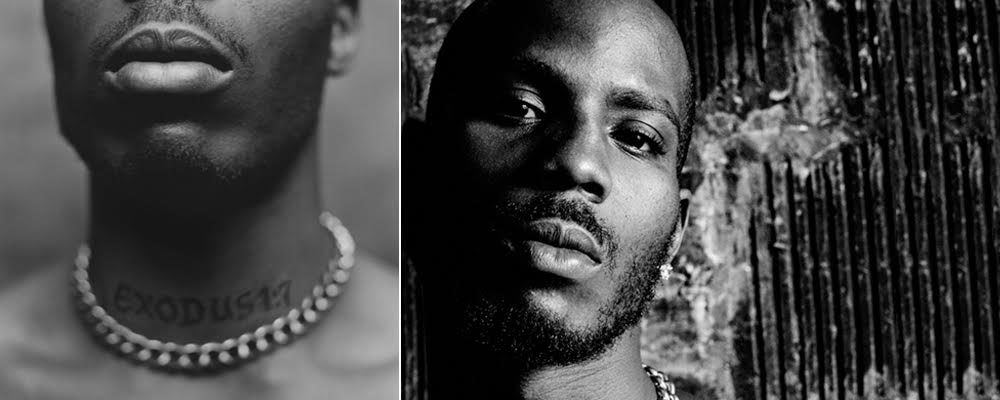

DMX’s Would-Be Comeback Album ‘Exodus’ Offers a Final Look at the Late Rapper’s Legacy

Todd Gilchrist

DMX was a singular artist. After a handful of iconic guest verses, including the explosive LL Cool J posse cut “4, 3, 2, 1,” the late Earl Simmons came roaring out of the gate with not one but two albums in the first major year of his career, “It’s Dark and Hell Is Hot” and “Flesh of My Flesh, Blood of My Blood,” and followed them up with a third, “…And Then There Was X,” less than 12 months later. If he couldn’t maintain that output — and no one could, or quite frankly should — he’d virtually secured his legacy already, and as uneven as his subsequent work may have been, there were always hits, but more importantly, there were repeated examples of the qualities that made him so unique, complex and unforgettable, juxtaposing violent and spiritual imagery in the same breath, exploring street stories, lyrical seductions and aspirations to higher powers with his raspy dog’s bark and a vocal chord-shredding yell that you couldn’t ignore.

“Exodus” sadly, marks the last project DMX worked on before he passed away; supervised and seen to conclusion by Swizz Beatz, the producer who shaped his rants into club-filling hits, it proves a worthy tribute to, and encapsulation of, the rapper’s talent and charisma, even a quarter of a century after he first growled into a microphone. Even where a parade of guest stars — and Swizz’s notoriously uneven hooks — occasionally risk overshadowing Simmons’ mesmerizing presence, his verses remain as insightful, incendiary, unrepentant, and redemptive as ever, adding to his expansive canon more than a handful of tracks destined that are soon to become classics.

As excited as one might be to hear DMX return to form, they must first get through Swizz’s frequently repetitive production choices; he’s never been especially versatile, but certainly since the release of “Poison” in 2018, the stutter-step, midtempo beats rank below Pharrell’s four-count intros in terms of originality, especially when they use the same drum sounds or samples. “Dogs Out,” which features Lil Wayne, for example, sounds almost identical to “Uproar,” also featuring Wayne, but more importantly, tinkling piano over chugging, skeletal beats. According to a recent New York Times interview with Swizz, with the exception of a swapped-out guest verse on “Money Money Money” (with Moneybagg Yo replacing the late Pop Smoke), this record was finished almost two months before Simmons passed away, but it’s unclear how much his collaborator tinkered with it before releasing it, and there’s something slightly odd about the positioning of DMX’s verses, frequently coming after those of his guests. Even if as Swizz indicated, X had to rebuild his confidence a bit during the recording of “Exodus,” it seems unlikely he would repeatedly choose to bat second or third on most of the tracks on his own album.

And so on “That’s My Dog,” the album opener, Swizz delivers one hook and then a second before turning the mic over to all three members of The LOX, and then DMX joins to deliver a verse full of some great one-liners (“I ain’t playin’ with you niggas, I got kids your age / I ain’t your father that shoulda stayed, too late, you shoulda prayed”) but overall not quite as consistent or focused as during his heyday. Jay-Z and Nas perform the first two verses on Track Two, “Bath Salts,” where Swizz turns NBA sirens into a brittle brass section as they both do what they do best — Jay flossing with glib, effortless one-liners (“I’m the King of Zamunda, uh, King of the Summer / Come be my Kardashian, queen of the come up”) while Nas digs deep for what is still some of the best wordplay in hip-hop history (“We ain’t in no relationship but do relationship things / No ring, but she slide through when I ring”). In the absence of a clear focus for the song, DMX’s palpable menace during his verse cements a throughline of three icons showcasing what makes each special. Third up is the aforementioned “Dogs Out,” whose familiar beat is no less a banger three years later, especially after Simmons clears out haters, competitors and hangers on like he’s the same hungry guy sparring with Redman, Method Man, and LL Cool Ja back in 1997.

Over a jittery harpsichord sample, Moneybagg Yo more than holds his own on “Money Money Money” before DMX takes Swizz’s baroque production and turns it into an anthem for aging gangstas, complete with some decidedly regressive but undeniably vivid lyrics: “Make niggas rape niggas, I hate niggas.” Over the next two tracks, guest singers — and not rappers — evidence DMX’s pivot to more introspective fare: first, Alicia Keys provides the hook for “Hold Me Down” as X qualifies his pedigree as a street poet (“I pulled in opposite directions, my life’s in conflict / That’s why I spit words that depict the convict”), and then Bono more unexpectedly does the same for “Skyscrapers,” where the rapper celebrates his struggle and wrestles with the comfort he’s achieved from fame.

After a 45-second skit, the first of two and perhaps the most retro inclusion on the record, “Hood Blues,” showcases Westside Gunn, Benny the Butcher and Conway the Machine, the members of rap group Griselda, as they and DMX cruise through a tour of a lifestyle that offers unattainable wealth and demands constant vigilance. The flute and funky bass underneath feels reminiscent of X’s “Crime Story,” leavened with the maturity of age and the boldness of being part of a posse: “I done punk’d more niggas than Ashton Kutcher / It’s Westside, Conway, X, Benny the Butcher, nigga.” DMX’s snarl has seldom translated to traditional sexiness in hip-hop terms, but he’s experienced considerable success by appealing to his female fans over the years (“How It’s Goin’ Down” and “It’s All Good” are among his biggest hits), and he adds another instant classic to this subset of his body of work with “Take Control;” featuring Snoop Dogg, whose shared Verzuz ranks among the internet series’ best installments, the two trade verses over a sample of Marvin Gaye’s “Sexual Healing” and ruthlessly objectify women in a way that only this particular genre continues to get away with.

DMX (or Swizz) seems to focus his strengths more narrowly at the end of the album, emphasizing the unwieldy but irresistible contradictions that made him so interesting to listen to during his heyday, reflecting on choices and challenges with clear-eyed honesty, blasting through obvious pain with desperate defiance, and eventually yearning towards forgiveness and hope. Nas appears for a thoughtful verse on “Walking In The Rain” in between choruses shared by X and his now five-year-old son Exodus; but it’s the one-two punch of “Letter To My Son (Call Your Father)” and what one presumes will be his final “Prayer” that sadly conveys the gravitas of his absence, and our loss. With Usher singing the chorus, DMX communicates hard lessons with unvarnished candor on the first track, and then offers a benediction — for the album, and for his career — with the latter.

Ultimately, DMX was an artist who existed, and perhaps could only exist, at a specific moment in hip-hop history; there are more than a few lyrics here that will deservedly attract more critical attention, even if his death may earn them a pass in this more progressive time. But for an artist whose singularity for, better or worse, may have poised him to flame out brilliantly, or to blow up his own success, “Exodus” reminds us that moment should have been longer, and that his legacy will endure — most of all as the embodiment of all of the contradictory instincts fighting within in his fans, searching for the grace that he never quite got himself.

“Exodus” releases May 28 on Apple Music.