Questlove’s ‘Summer of Soul’ Revisits Harlem’s Glorious 1969 Summer Cultural Festival

Alci Rengifo

“Summer of Soul (…Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised)” confirms that some documentaries can be so absorbing, so transcendental, that the viewer doesn’t so much watch them as absorb them. A labor of love by Questlove, this documentary is many potent things. In the summer of 1969, as much attention was being garnered by Woodstock and the Moon landing, massive crowds gathered at what is now know as Marcus Garvey Park in Harlem for a stirring cultural event. It was the Harlem Culture Festival, and over the course of six concerts the music performed encompassed all the history, struggles and major changes of an era.

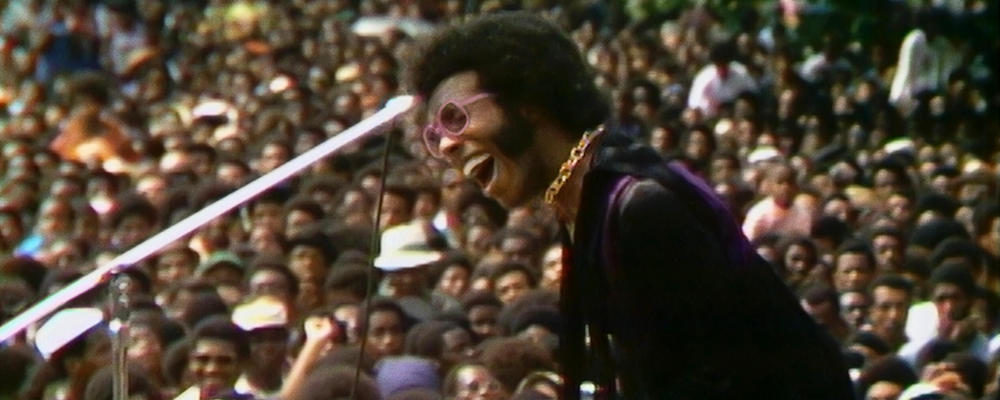

It took an accomplished musician like Questlove to make this project because he knows how to keep the music at the forefront, while never losing sight of the meaning of it all. Surprisingly, this is history that had simply sat for over 50 years. The various performances throughout the summer festival’s run were shot by Hal Tulchin, a TV director who could not find a single interested buyer for the footage after the concert series concluded. Thankfully the 47 reels of footage Tulchin shot are so crisp, so intimate, that they allowed Questlove to make a fresh epic out of the material. The roster of featured artists are a long list of legendary performers and musicians. The emcee is radio personality Tony Lawrence. Among the acts featured we get Nina Simone, Sly and the Family Stone, B.B. King, Gladys Knight & the Pips, Stevie Wonder, Mahalia Jackson and the 5th Dimension — and for attendees it was all free. The original intent was to promote cultural celebration and harmony in the wake of riots following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and continuing political conflict, not least over civil rights and the Vietnam War. The Black Power movement was just emerging, and much security for the concert was carried out by the Black Panthers.

Along with a few surviving artists, Questlove also interviews those who were in the audience, like Musa Jackson, who looks visibly moved, almost as if in a joyous trance, when looking at the footage of the packed park, the crowds of mostly Black Americans dressed in the changing styles of the time. Jackson admits to being hypnotized by the beauty of the 5th Dimension singer Marilyn McCoo. The personal and the wider, social impact of the music and its roots are beautifully rendered. It is as if by reviving the Harlem Culture Festival, the documentary is able to encapsulate all the different rivers of influences, roots and stories that form Black America’s timeless music. When David Ruffin of The Temptations hits the stage like a one-man charisma emitter, crooning “My Girl” with soaring skill, we learn about the enduring importance of Motown’s sound. Sly Stone is an even more glorious diva, purposefully taking his time onstage, but when he does, he and the band let it rip. And to have a white drummer and Black female trumpet player at the time inspired many in attendance to the power of music as a universal force. Stevie Wonder remembers finding the courage to experiment with his sound and be politically outspoken, but your eyes are dazzled by a drum solo Wonder pulls off with a combo of pure joy and precision.

Al Sharpton appears in “Summer of Soul” commenting that 1969 was the year the term “Negro” was officially replaced by “Black” as a sign of a renewed pride in the Black American community. It is quite special how Questlove conveys the way music in the ‘60s went beyond entertainment, it was a revolutionary force. The social revolution brewing amid all the struggles of the time fed the art of the era. When Sonny Sharrock played a scorching guitar solo or Max Roach wailed on the drums, they were expressing the tinderbox feelings of a whole society demanding change. South Africa’s Hugh Masekela plays a breezy “Grazing in the Grass,” but he signaled a new link between music from the African continent and the U.S., as Black American activists looked abroad, to the struggles in South Africa and nearby Latin America with a sense of solidarity. Jesse Jackson appears onstage to proclaim “Black is beautiful” while denouncing economic inequality. The power and influence of the church are given a necessary importance when interviewees discuss so much of the sounds on display. Legendary gospel singer Mahalia Jackson performs “My Precious Lord,” in tribute to Martin Luther King Jr., in an astounding, soul-shaking duet with Mavis Staples. Such moments make one forget the spot where the documentary is being watched. You are there, in the moment.

Visually what makes “Summer of Soul” so stunning is the sheer clarity of Tulchin’s footage. He explains to Questlove how the budget for the festival was so low, with Maxwell Coffee being the one major sponsor, that his crew couldn’t even afford decent lighting. So he simply made sure the stage was designed in a way where performers would always be facing the sun. Because the footage was for television, there isn’t the grainy look of images from the past. Everything is so razor sharp, with close-ups of these icons, from their hands on the piano keys to their faces in the middle of hitting a high note, that it’s astounding to even consider some of them have long passed away. Other moments have a bit of intriguing but socially conscious humor, like the fact that the festival was going on as Apollo 11 landed on the Moon. Some concertgoers express admiration for the accomplishment, but wonder why they should care when the U.S. government refuses to invest some of that money in poor communities. Surviving artists who speak with Questlove offer some great memories too. Marilyn McCoo tears-up watching the Fifth Dimension performance of the classic “Age of Aquarius,” recalling her pride at performing in Harlem at a time when their band was slammed as “too white.”

“Summer of Soul” celebrates Harlem, the Black American struggle, astounding music, and much more. It is through so much of the music in this country that its diversity and identities mingle. Latin bands from the time perform onstage, with rhythms that have everyone moving, and Lin-Manuel Miranda comments on the importance of Caribbean and Afro-Latin music. The Festival also emphasized the mixture of Black American, Puerto Rican, Cuban and other Latin communities in the city and beyond. This documentary certainly rivals “Woodstock” in its scope and energy. While that great film remains a perennial classic, “Summer of Soul” has a striking relevance for today. Many of its themes and issues are still with us. The great Nina Simone stands during her set and begins reading a militant poem that would have still resonated just as powerfully last year during the Black Lives Matter protests. But please, while taking in all this documentary has to offer, try to stream it on a large screen. With its powerful memories and rhythms, it is a work to take in and escape with.

“Summer of Soul (…or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised)” releases July 2 in select theaters and Hulu.