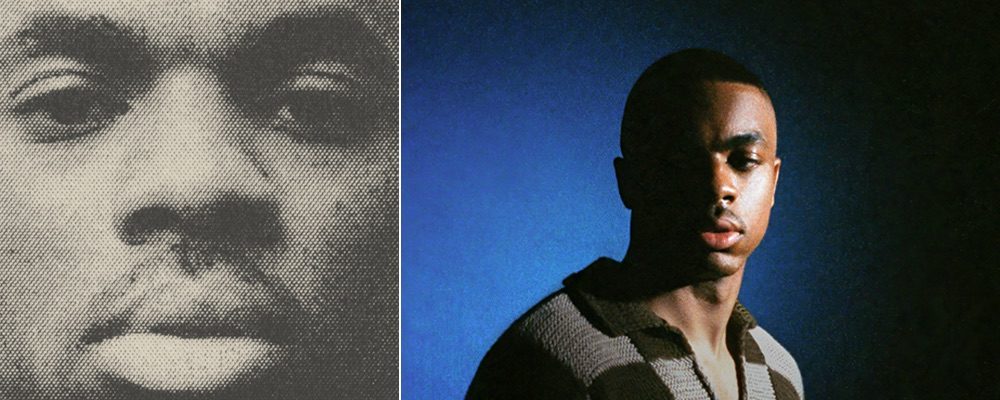

On His Fourth Album, Vince Staples Offers Authenticity but Little Variety

Todd Gilchrist

At 22 minutes, Vince Staples’ new self-titled album runs barely long enough to qualify as an EP. But in an era frequently defined by maximum output, minimum effort, the three-year wait for its release somehow elevates Staples’ artistic intentions, even if listening to it doesn’t quite validate them. Between two actual EPs, four mixtapes, five albums and another on the way, the acclaimed solo artist has explored an eclectic variety of sounds that some of his former Odd Future associates expanded into more full-bodied and distinctive musical expressions, from soul to Detroit techno. “Vince Staples” settles comfortably into the rhythms of trap for a journey that occasionally hints at something deeper and more personal, but its brevity, repetition and lyrical content underwhelms what should be an exciting return for a dynamic rapper and performer, reducing it to a perfunctory stopgap from his absence.

If hip-hop will likely never have a reckoning about its objectification and misogyny against women, there have at least been a few performers, from Snoop Dogg to Notorious B.I.G. to Too Short, who indulge it with a relative degree of imagination, while others distract or muscle through with catchy music. Like many before him, Staples liberally uses the word “bitch” during the record’s 22-minute running time — and depressingly, almost none of it expresses a real point of view. It’s part of a greater paranoia and mistrust of pretty much everyone on “Law of Averages,” where he opens with “Fuck a bitch, I don’t trust no bitch with my government,” then later insists, “I will never give my money to a bad bitch.” By the time he builds it into the chorus of “Lil Fade” (“So what’s up with it, tell me if it’s up, bitch”), it’s almost become an abstraction, but its repetition undercuts the rapper’s gift for vivid lyricism, and the songs are too short to develop more complex ideas, much less tell any kind of story.

Kenny Beats produces the entire album, and his trap style suits Staples’ no-nonsense style but it doesn’t develop a lot of variety over the album. After the wavy synths of “Are You With That?” opens “Vince Staples,” an uncredited James Blake (or a James Blake soundalike) opens “Law of Averages” as Beats manipulates the vocal sample to weave around Staples’ monotone verses; it takes skill to inject the rapper’s flatness with emotion, even when he’s cataloguing a world that either seems out to get him or get something from him, and the producer almost pulls it off. Next, “Sundown Town” reiterates Staples’ get-paid-or-get-killed worldview and paints an evocative portrait of the poverty and crime he grew up in that formed it. But the problem that quickly emerges is that even if these are fully authentic expressions and self-portraits for the rapper, there’s very little to distinguish them from what has now become decades of gangsta rap chronicles. Staples doesn’t develop any of these ideas into greater narratives or provide deeper insights, so it ends up sounding like the same thing that listeners have already heard, many times over.

“I live out every word I put inside my verse,” he raps on “The Shining,” and it may be true — but is there a reason to care? The question quickly becomes, why listen to this now? B.I.G.’s verses on “Ready To Die” were angry and aggressive, vital and unforgettable, but two years later on “Life After Death,” even he had mellowed a bit, a seasoned Carlito Brigante to his previous record’s Tony Montana. It’s been almost 25 years since then, and Staples barely seems able to muster the energy to complete a song, so what makes this music unique or special or even just enjoyable to listen to? Kenny Beats begins to inject a richer sound into the record over its second half, but a track like “Take Me Home” feels more like an also-ran version of some better-known and probably more expensively produced late 90s neo soul song, especially with a chorus sung by Fousheé. There, the rapper gets contemplative (“When it’s quiet out I hear the sound of those who Rest In Peace / Tryna drown the violence out”), and together he and his guest star create a melancholy tribute to a lifestyle defined by violence and loss, wishing like Dorothy in “The Wizard of Oz” to be taken to a place of comfort and safety: “Take take take me home like I clicked my shoes.”

Staples closes the album with what effectively amounts to an interlude, “Lakewood Mall,” and the slightly peppier “Mhm.” On “Lakewood Mall,” guest vocalist Tyson recalls a long day’s hangout that ended in violence Vince narrowly escaped, but other members of their crew did not; it’s a cautionary tale speaking to Staples’ sense of self, and his independence even among a tight-knit crew. “Mhm” provides a fitting conclusion to the album, and encapsulation of its themes, as he juxtaposes the lifestyle he used to lead (“fore corona I was at Ramona with a mask”) with the one that he does now — and the responsibilities it sadly places on his shoulders (“Hundred on his headstone / homies call me rich Cuz”). But as true and accurate and inspired by real experiences as Vince Staples’ music remains, in a genre filled with rappers insisting their art reflects their past and present realities, “Vince Staples” unfortunately feels like a retread. It’s fair if expression of that reality is enough for him, but at this point in hip-hop’s history, it’s also reasonable to expect more.

“Vince Staples” releases July 9 on Apple Music.