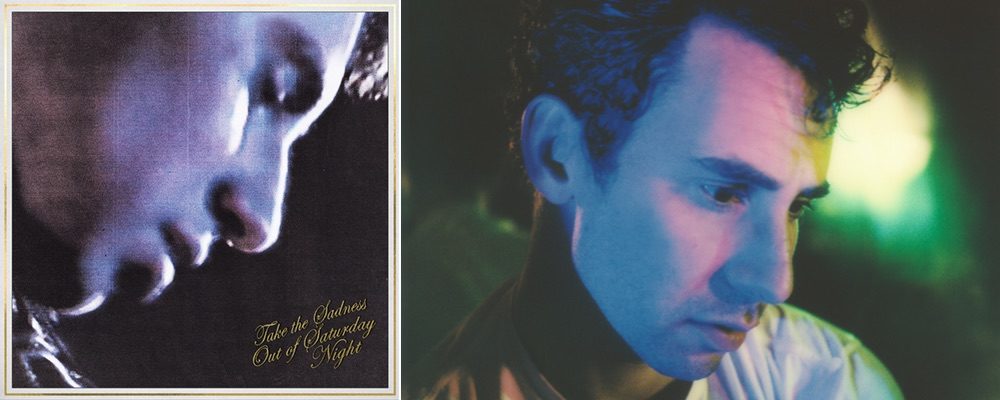

Jack Antonoff Searches For Fulfillment on Bleachers’ ‘Take the Sadness Out of Saturday Night’

Adi Mehta

As a producer and songwriter, Jack Antonoff has been the transformative power behind artists like Taylor Swift, Lana Del Rey, St. Vincent, and Lorde, tweaking sounds and enacting changes in the pop landscape. Antonoff has also released his own music under the moniker of Bleachers since 2014. His debut album, “Strange Desire,” demonstrated a committed ‘80s fixation, and an ability to hint at broad pop appeal within these confines. At times, it sounded like Antonoff was haphazardly turning every type of music he found into synth-pop, with R&B, pop punk and an actual feature from Yoko Ono all vying for attention from depths of reverb. His 2017 album “Gone Now” followed course, but expanded the parameters, and found Antonoff darting between genres with a giddy enthusiasm that easily won listeners over. For Bleachers’ latest release, “Take the Sadness Out of Saturday Night,” Antonoff continues to build most of his songs largely from ‘80s inspirations.

However, this time Antonoff strays considerably from the synth-pop stylings of previous efforts, and settles in a much more specific domain, in which the dominant influence is Bruce Springsteen. The new tracks see a stylistic shift toward these sounds, but also digress, with new freedom, into whatever style he finds suitable for a given song. Antonoff makes strides in his conceptual crafting, with a clever way of putting his influences to creative use. He not only pays homage to Springsteen, but utilizes his music’s evocative power and cultural significance. Antonoff conjures specific attitudes and ideas linked to Springsteen’s sounds, and uses them as a songwriting conveyance as he dips into various mentalities in songs that explore disconnect, desire and hope. The new album is more driven by serious lyrics than previous efforts, while the musical stylings are varied to capture different perspectives and moods with a new illustrative potential.

Opening track, “91,” is an unanticipated musical departure taken toward a specific thematic end, as Antonoff reveals a realization at the core of broader matters explored in the album. Written with the guidance of author Zadie Smith, the song relies on effective literary crafting, with each verse recontextualizing the climatic lines, “Hey I’m here, but I’m not / Just like you, I can’t leave.” Antonoff’s natural, unmannered singing comes over a backdrop of outlandishly florid strings, with the juxtaposition effectively demonstrating a disconnect from the surrounding world. With this groundwork laid, Antonoff leaves listeners to make whatever sense they can of the colorful contents that follow.

Bruce Springsteen-featuring single. “Chinatown,” surprisingly has an overall contemporary ring, compared to the caricatural ‘80s sounds that dominate Bleachers’ back catalogue. The stylings of Springsteen are all over, but a few levels removed. Antonoff’s vocal flaunts any gestures obviously derived from the boss. Yet, his delivery is considerably stylized, and his persona is a composite. He bares his roots, but appears to move freely past them, as he sings, “I’ll take you out of the city / Honey, right into the shadow.” Chinatown’s place on bus routes makes it a common reference point for new tourists venturing into New York. In the context of the song, the titular locale leaves subjects vulnerable to the influence of the grey area that directed the development of Antonoff’s artistry — New Jersey.. Because of its proximity to New York CIty, Jersey is prized with power over movement in and out of New York. The new single explores this power and simulates the journey “out of the city.” When Springsteen enters, he sounds raw and raspy as ever, singing the same chorus as Antonoff but with new authority. At this point, we are out of the city. The idealism shared by entire town populations, an idealism built on Springsteen’s music, has been traced back to the source. As the song’s speaker reaches vaguely for unattained dreams, declaring, “I wanna find tomorrow / With a girl like you,” the shift from New York to Jersey, Antonoff to Springsteen, and inspired to inspirer, shakes up the transmission of the lyrics, leaving unresolved questions about trust and biases.

Unfulfilled desires are addressed more directly in “How Dare You Want More.” Antonoff has spoken about a palpable unease that people often display, when admitting general yearnings for more in life. In this number, his stylings again recall Springsteen’s music, but now he stretches them to rather comical excesses. A chorus of voices celebrates the decision to live large on a particular evening, over a musical backdrop more concerned with maintaining the illusion of festivity than achieving the reality. Stigmatic ‘80s saxophone bits effectively drive this home, and the song culminates in an anachronistic guitar and sax solo exchange that is easily the album’s silliest moment. “Big Life” is a further pronouncement of the same situation, with the concerted chorus now admitting, “We’re after the big life,” Sloppy harmonies mimic the overenthusiastic, uninhibited voicings of the masses as they stumble on in hopes of greater fulfilment. Ultimately, Antonoff strings together a catchy, Springsteen-inspired song, and sounds like he’s having plenty of fun performing it, perhaps wishing he could be fully swept away by the sentiment. “Secret Life,” a sister track to “Big Life,” explores a common alternative that stems from the same yearning. Worlds aways from the preceding track’s colorful revelry, this song is understated, like the “secret life” it describes with a simple acoustic arrangement. The guitar lead finds Antonoff simply bending a note repeatedly, and producing a heavily processed end sound, representing the easy indulgence behind the appeal of a “Secret Life.” Lana Del Rey joins in the end, gently singing along, offering a faint voice of validation to the unspoken yearnings.

“Stop Making This Hurt” returns to overdone ‘80s rock ‘n’ roll stylings, with the spectre of the boss still at close reach, and more sax frivolities thrown in. This time, Antonoff focuses on needless drama in uncertain romantic relationships, but elicits the same latent escapist ambitions that previous songs brought out. “Don’t Go Dark,” a particularly catchy Springsteen-styled ditty, takes up a similar focus, as Antonoff resists a partner’s emotional baggage. His slightly strained voice suggests an attempt to temper emotions, while his use of the “slapback echo,” best known from innumerable Elvis songs, sustains his voice for a split second, as he struggles to reach for bigger dreams. The simple desire to remain happy, perhaps to “take the sadness out of Saturday Night,” remains at the core.

Antonoff turns out compelling, thoughtful songs, even when he casually jumps from one imagined perspective to the next. In the particularly poignant “45,” he explores the phenomenon by which people lose pieces of their identity over time, and fill the void with pieces of others. He uses minimal, acoustic guitar backing, but with propulsive strumming, fit for a speaker who is anxious to assert that he is still there, as he notices, “Our 45’s / Spinning out of time.” Compared to the measured aggravation of “Don’t Go Dark,” this song rings with a winsome tone of earnest optimism. All that remains at this stage is to put the positive mentality to effective use. This more abstract pursuit is the focus of the final two songs. “Strange Behavior” is a more internal rumination, fit to the most uncluttered arrangement yet, Musical gestures are mere hints of ideas, with incidentals like the scraping of fingers on the fretboard reminding us of the realities at play. An indecipherable falsetto utterance constitutes the chorus, and suggests a withdrawn perspective from a dreamlike state. The final track, “What’d I Do With All This Faith” offers a limited resolution by fitting the remaining challenge to a hummable refrain, and presenting it with a comfort that suggests at least a partial triumph for idealism.

“Take the Sadness Out of Saturday Night” is the most conceptually defined Bleachers album, as well as the most thoroughly realized. The music itself might seem less focused than that of previous releases, but when taken with the lyrics, it is masterfully crafted to purpose. Sorting the songs by the type of musical treatment applied can shed some light on Antonoff’s perspective. As he picks song subjects by reflecting on sources of unease, as part of a general effort to improve life, Antonoff appears to measure everything he encounters by the extent to which it fits into the world represented by Bruce Springsteen, in which positivity and idealism are key qualifiers. Indeed, the most overtly Springsteen-styled songs of the album are playful, upbeat numbers dedicated to having good times, Meanwhile, the disapproving voice in “91” is too grave for any Springsteen stylings. The speaker of “Secret Life” is too duplicitous, and the last two tracks are too weary and withdrawn, too openly vulnerable.

All of these songs offer an insight into what sets Jack Antonoff apart as a songwriter. Antonoff has spoken before about the importance of fitting a song’s sound to the voice that delivers it. While this is hardly an original thought, the new Bleachers album shows how far he is willing to take it. Antonoff crafts every song with musical stylings and production choices that fit its perspective and content. In retrospect, the foolhardy genre hopping of earlier work seems to have been invaluable, as Antonoff adopted different voices and explored disparate musical styles. Now, he can pick a persona from the vast selection amassed, and shift shapes as needed, envisioning songs in voices and styles that suit them. He splits singing duties among the various characters that he plays, and allows new realities to take shape from the collective vitality of his songs, bringing the album to life.

“Take the Sadness Out of Saturday Night” releases July 30 on Apple Music.