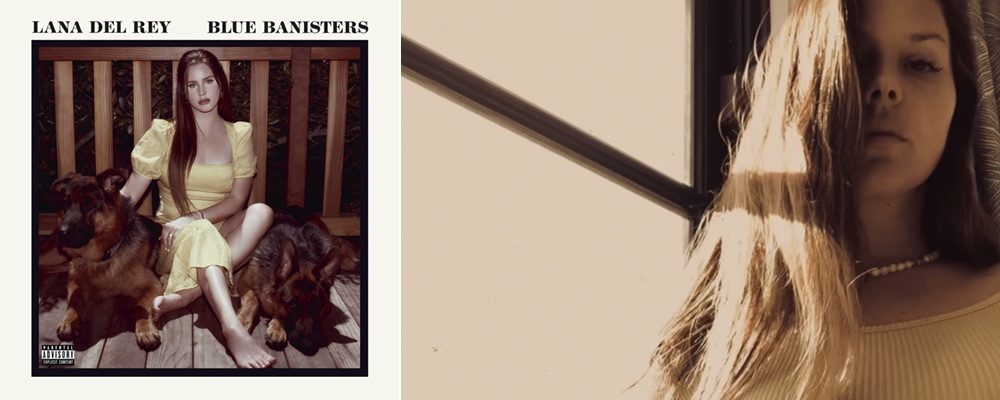

‘Blue Banisters’ Captures Lana Del Rey at Her Most Delicate and Daring

Adi Mehta

When Lana Del Rey followed 2011’s breakout single “Video Games” with 2012’s album “Born to Die,” her music seemed like part of a greater performance art. Del Rey’s Hollywood sadcore sound borrowed heavily from nostalgic stylings of the ‘50s and early ‘60s, and recast them in contemporary vernacular and production, alongside such disparate influences as psychedelic rock and hip-hop. Her unabashed Upstate New York gone L.A. persona pulled its inspiration from Old Hollywood stereotypes with an indeterminate amount of irony. After five memorable studio albums, Del Rey’s songwriting and aesthetic found their most masterful realization on 2019’s “Norman Fucking Rockwell.” Since then, she has released a book of poetry, “Violet Bent Backwards over the Grass,” alongside an accompanying spoken word album, and another record, the delayed “Chemtrails Over the Country Club,” earlier this year. She also, once again, become embroiled in controversy. This time, Del Rey wasn’t combating accusations of glorifying abuse and appropriating cultures, she was defending her continued string of ill-advised social media posts. As a result, Del Rey announced that she was withdrawing from social media at large. But her latest delayed album, “Blue Banisters,” still made its way to streaming services. The new record feeds off the freedom found in the resulting space, and thrives off the drama accrued from the charges leveled at her. Compared to her album earlier this year, “Blue Banisters” considerably strips back the production and takes more liberties, with Del Rey resting on the strength of her songwriting and embracing her quirks with a new boldness.

Opener “Text Book” begins with a disclaimer of sorts, “I guess you could call it textbook,” which is a discerning way to start the record, considering that a shtick as stylized as Del Rey’s should naturally have started to wane by the point of the eighth album. With this noted, Del Rey promptly proceeds to business as usual, donning the voice of a damsel in distress and telling a tale of Freudian transference with a throwaway directness that ever so slightly approaches self-parody in lines like “You’ve got a Thunderbird / My daddy had one, too.” Early ‘60s signifiers usually make their way into Del Rey’s songs, but often a few levels removed. Here, they guide the song undiluted, with stylings that vaguely evoke early Bond themes. The song takes liberties with its structure, leaving trails of droning bass, over which Del Rey sounds equally playful and devilish, before locking into an unanticipated beat for the cathartic chorus.

The title track continues in this vein, and it seems like the new unhurried and spacious musical directions are informed by Del Rey’s recent withdrawal from the public eye. She fills the track with her usual Americana imagery, describing “a picture on the wall / Of me on a John Deere.” She sings about “swimming with Nikki Lane,” with whom she collaborated in “Breaking Up Slowly” from “Chemtrails.” She sings of a man in her past who “said he’d come back every May / Just to help me if I’d paint my banisters blue,” hinting at a pressure to seem fragile and troubled, and goes on to recall being told, “You can’t be a muse and be happy, too.” Until now, Del Rey has only defended her right to play up her delicacy, amid the accusations from feminists, but the idea of her feeling obliged to conform to such expectations is somewhat surprising. A sentiment more consistent with her general posturing comes in “Violets For Roses,” when she sings, “God knows the only mistake that a man can make / Is tryin’ to make a woman change and trade her violets for roses.”

On “Arcadia,” Del Rey declares, “My body is a map of L.A.,” a premise that grows more comically absurd with lines like “Trace with your fingertips like a Toyota.” Chevys and Fords have long been featured in the Americana imagery of Del Rey’s lyrics, but a Toyota seems like an odd choice. Taken with the other lyrics, it seems Del Rey is expressing a disillusionment with the direction of American culture, particularly cancel culture, as she continues, “They built me up 300 feet tall just to tear me down / So I’m leavin’ with nothing but laughter, and this town.”

A third of the way into the album, the songs especially begin to take the form of heightened dramatic performances in a greater narrative. On “Black Bathing Suit,” Del Rey sounds decidedly worn, running through the motions, and scrunching up her lips with faux sincerity at key moments, then letting loose in a chorus full of deranged exclamations. She returns to the social media backlash, claiming, “There’s a price on my head,” and smugly declaring herself the ultimate winner in the controversy, adding, “Your interest really made stacks.” On “If You Lie Down With Me,” she sings slightly slurred, with a snideness that reaches epic proportions in a “la la la” chorus in which the la’s reveal themselves to be truncations of the word “lie.” The surprises continue when “lie” changes meaning, leading into the titular invitation, “Lie down with me.” “Beautiful” features a chorus in which Del Rey insists, “You’re beautiful” three times and finishes with a melodic phrase that makes it clear the song is a play on James Blunt’s mawkish 2005 single, “You’re Beautiful.” Del Rey issues her variations like deranged pleas, strained and left suspended, while a prickly piano sketches oblique figures around the edges, hinting at an idea out of reach. She dials up the irony further on “Thunder,” in which gospel choirs make their way into the chorus, bolstering her encouragement to a departing partner, “Just do it, don’t wait.”

On “Wildflower Wildfire,” Del Rey sings deadpan with fleeting moments of blood-curdling contortions, which give way to bouts of passion and witchy, whispered harmonies. When she erupts into sweeping choruses, she does it in a sort of perfunctory passion, like a jaded actress running through a stage routine. On “Nectar of the Gods,” lines like “I get wild on you, baby / I get wild and fuckin’ crazy” take on an entirely different form than one might expect from a glance at the lyrics. The alienation intimated in “Arcadia” resurfaces with the scorn that has worked its way into the few preceding tracks, as Del Rey abruptly ends the song, “Californ-I-A, homeland of the Gods / Once I found my way, but now I am lost.” On “Living Legend,” even Del Rey’s most designedly sweet pronouncements come across with disdain, and maudlin lines like “And, baby, you, all the things you do” are delivered with a chilling quiver.

“Dealer,” featuring Miles Kane, is a definite standout, with Kane’s relatively measured singing providing an effective counterbalance for some of Del Rey’s most daring vocals yet. Kane insists, “Please don’t try to find me through my dealer” over a beat that trudges along monotonously, while Del Rey’s singing escalates into unhinged wailing and full-fledged screaming. The other most dramatic novelty comes in the closer, “Sweet Carolina,” co-written with Del Rey’s father and sister. Here Del Rey takes up a fluttering falsetto that wouldn’t sound out of place in a Kate Bush song, then returns in a flash to her usual California cool. At one point, she nonchalantly narrates, “‘Crypto forever,’ scrеams your stupid boyfriend / Fuck you, Kevin.” And why not?

Oddball bits like this speak to the uncompromising creative freedom that characterizes “Blue Banisters” as a body of work. It’s an album that finds Del Rey eschewing instant accessibility in favor of songs that follow whimsical structures and feature some of her more eccentric displays, in terms of both lyrics and performance. This works well, as Del Rey’s songwriting is so firmly rooted in nostalgic stylings that the songs always have a classic ring to them. This timeless quality is balanced by lyrical references that ground the material in the present moment, as well as in Del Rey’s particular situation, regarding the type of controversy that has surrounded her recently. Her critics have clearly added fuel to her fire, and this album reveals a bold disregard that ultimately keeps her camp aesthetic fresh. “Blue Banisters” is not the immaculately rounded, potent record that “Norman Fucking Rockwell!” was, but it’s quite safe to say it wasn’t intended to be. Del Rey sang on that album about being “obsessed with writing the next best American record,” but at this stage, she is releasing content at an impressive rate, with a constant stream of ideas that need to be directed through the appropriate channels. If “Chemtrails Over the Country Club” was Del Rey fitting herself into a new mold, “Blue Banisters” is her freeing herself from its constraints and simply letting the ideas flow.

“Blue Banisters” releases Oct. 22 on Apple Music.