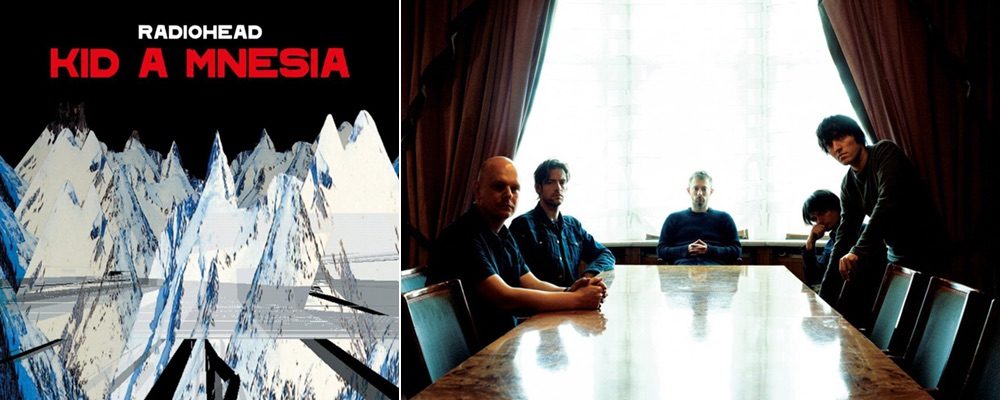

‘Kid A Mnesia’ Looks Back at the Millennial Metamorphosis of Radiohead

Adi Mehta

In 2000, popular music had not yet splintered into the infinite microgenres of today, and a Y2K-weary world took comfort in the prospect of a new Radiohead record. The unanimous critics’ darlings had brought the art of the great rock album to its historical apex with 1997’s “Ok Computer,” and would surely do it again. A scant few knew that frontman Thom Yorke had long been voicing his frustration with the stale alternative rock format. He had become immersed in experimental electronic fare, and guitarist Johnny Greenwood was already a bona fide classical composer. So it’s really not all that surprising that when the album arrived, there were no guitars erupting into distortion on cue for stadium singalongs. Nevertheless, Radiohead released “Kid A,” followed a year later by “Amnesiac,” and one could say the world has never been the same. Surely, you have encountered upstanding adults who complain about a breed of sensitive misanthropes who insist that music can only be good if it sounds bad. Granted, such people always existed — there have always been enthusiasts of Captain Beefheart. But after 2000, they were suddenly everywhere. Radiohead’s fourth and fifth albums made the persuasion wholesale. Somewhat ironically, that era is being celebrated with a blatantly wholesale type of promotion. “Kid A” and “Amnesia” have been issued together as “Kid A Mnesia,” with a third disk of rather haphazardly selected outtakes from the same period.

With two transformational albums now packaged together, and a third assembled from loose ends, there has never been a better time to listen to “Everything In Its Right Place.” The “Kid A” opener could easily be the most powerful track of the whole set. Its opening chord sequence loops in odd timing, grounding you in an oblique, meditative space, as warped splinters of Yorke’s outpourings whirl, collide, and coalesce. By the point when Yorke is piecing together the line, “There are two colors in my head,” the magic of “Kid A” should have begun to work on you, and you’ll soon learn, or remember, that it has only begun.

A couple tracks in comes “The National Anthem,” with Yorke singing, “Everyone is so near / Everyone has got the fear / It’s holding on.” Given the title, he seems so believe that what binds us together is our collective claustrophobia — shared struggles and anxieties. Of course, he sings this deadpan, nodding to a steady beat, fleshing it into feelgood fare the same way he did back when he declared, “I’m a Creep.” The track eventually devolves into riotous free jazz excesses that led Johnny Greenwood to name it as his favorite of the record. Still, any attempt to even isolate a song for the sake of explanation detracts from the scope and scale of the work at hand.

Acoustic beginnings fade into ambient colorings, reemerge and build into the swirling, dark reverie of “In Limbo” over four successive tracks. Then comes the truly unparalleled “Idioteque.” The band goes full electronic, resting on a minimal drum pattern and a synth refrain sampled from experimental computer music composer Paul Lansky. Yorke’s vocal phrasings are downright alien, and the song comes across like a sort of dance pop in an alternate universe. Compounding this is his deranged delivery as he describes “mobiles skwerking, mobiles chirping,” and insists, ““We’re not scaremongering / This is really happening.” The world is becoming unsettlingly mechanical, and at a given moment, no one ever knows for sure whether we really should be freaking out.

This was the new Radiohead. At any rate, Kid A made its mark, and “Amnesiac” was largely received as a gentle circling back to convention, even though the songs that make up both albums were recorded in the same sessions. In admirably Radiohead style, the band objected to a double album, in aversion to the connotation of rock star excesses. While there is more guitar and recognizable instrumentation on “Amnesiac,” there is also as much, perhaps more, experimentation. Kid A derives more of its force from space and gesture than its sister album, which veers far out, but generally assembles the band’s avant aspirations into substantive semblances of songs.

Tracks like opener “Packt Like Sardines In a Crushd Tin Box” and “Pulk/Pull Revolving Doors” reflect Yorke’s growing electronic influence more than anything on “Kid A,” with skittering beats and morphing textures that noded to ‘90s glitch heroes like Aphex Twin and Autechre. Meanwhile, tracks like the epic “Pyramid Song” thrive off voice and piano intimacy, but warp and scale it to staggering ends. The swift gestures of strings trigger plate tectonics, and Yorke’s haunting melodies soar to epic heights around chaotically concerted jazz drums. Such rapturous numbers are interspersed with outliers like Knives Out.” Although often cited as an example of how much more straightforward “Amnesiac” is, the tune takes Syd Barrett liberties with its structure, cutting out a measure here, adding three more there, trailing off freely on tangents, and always appearing to keep a straight face.

While “Amnesiac” deserves more appreciation relative to “Kid A,” the bonus disk that comes with “Kid A Mnesia” is a different matter. The compiled material begins with “Like Spinning Plates (‘Why Us?’ Version),” which many fans will recognize from the band’s live renditions. Yorke’s backwards vocals have been stripped from the verses, replaced with the straight-shooting, intelligible variation that stood the world up on “Kid A.” The backwards music too is largely scrapped in favor of a central melodic figure. Chances are that the band systematically dismantled the song on “Amnesiac” to remove any elements they deemed too cliche. The unreleased version is not as hypnotic or immersive as the “Amnesiac” cut, but an enjoyable variation that shines from its balance of organic and abstracted sensibilities.

“Fog” is a song that has seen similar reimaginations over the years. It first appeared as simply “Fog,” on 2001’s “Knives Out” EP, as an organic band effort, albeit one covered in the final mix with a layer of sputtering glitch artifact. Yorke’s voice was also soaked in reverb, so that the ultimate sound was removed and ethereal. Later, on 2004’s “Com Lag: 2+2=5 EP,” we heard “Fog (Again) [Live],” a no-nonsense, unplugged version featuring just Thom at the piano. Now, we get “Fog (Again Again Version),” which takes an alternate approach to abstraction. The music that Yorke sings over is a dynamic end of much tinkering, in line with some of the sounds on “Pulk/Pull Revolving Doors,” but for some reason, a drum beat too basic to even exist has been placed under this, with the kicks and snares falling at awkward spots and detracting considerably from the song.

The only song on the list that hasn’t been released before in some form or other is “If You Say the Word.” With acoustic guitars alongside illuminating electronic flourishes and dramatic orchestral gestures, it fits right into the era of “Kid A Mnesia,” particularly echoing the aesthetics of “How to Disappear Completely,” The jazz drumming that made it way into “Pyramid Song” and so many cuts from the Com Lag: 2+2=5” EP also place the track in that era. The guitar strums out a separate rhythm from what the drums move to. Crashing chorus gestures come in classic keyboard stabs and eerie, high-pitched projections that impart a camp, retro-futuristic feel, and the song rings with all of Radiohead’s celebrated idiosyncrasies.

“Follow Me Around” has floated for years, and could well be Radiohead’s least engaging song. A one-riff verse-chorus-verse that drags on for over five minutes, it would make sense if designed to simulate the sensation of being followed around. The monotonous plodding weighs on you, and the tune winds back incessantly to a nagging chorus. You could be optimistic and welcome the song’s length, in hopes that the singer will eventually run out of words or breath, but when the words finally stop, it springs back, now merely groaning and humming, with unintelligible noises growing increasingly outlandish in the chorus.

Relief comes in “Pulk/Pull (True Love Waits Version),” literally a mashup of the eponymous “Amnesiac” track and the fan favorite that floated for ages before being reimagined as the finale of 2016’s “A Moon Shaped Pool.” It appears that they have simply layered the latter song’s vocals on the former. It works well enough because the ambiance all settles into a harmonic cloud around a droning, resonant center. While this mix is notable for its novelty, “True Love Waits” derives more from a purposed arrangement, and “Pulk/Pull Revolving Doors” works on you more fully when there are no readily intelligible words to distract you.

Along with these tracks come three short “Untitled” interludes that express vivid volumes in their brief running times and effectively extend the spirit of the original sister albums. Avid fans will get a thrill from picking out familiar sounds from the collages, like an instrumental bit from “Pulk/Pull Revolving Doors” and the processed vocal of “Kid A” in the first piece. “The Morning Bell (In the Dark Version)” sounds like a demo version of the “Amnesiac” cut, with lower frequencies pulled out. It’s a novel take, although a bit bare and quite random. “Pyramid Strings” is a full-fledged, avant garde compositional effort that makes for a high point, “Alt. Fast Track,” is an electronic aside that twitches swivels, flashes, and flickers, but sounds like a rather shabby demo of the version from 2001’s “Pyramid Song” EP. “How to Disappear Into Strings” merely scraps the vocals and guitar from the “Kid A” number, but ends up illuminating in just that end. Its familiar ring and spacious scaling make for an effective closer, and make a case for Greenwood’s insistence that live classical music should be watched. Just from listening to this without vocals and guitars, it becomes a fluid experience that takes place in three dimensions, with the dependence of your particular experience on your specific physical position in the mix becoming obvious as the piece runs its course.

Even if an unreleased Radiohead song is cause for celebration, there is only one on this collection. The other “new” tracks are largely variations, mostly inferior cones, of songs that have surfaced outside of full-length album tracklists for years. The selections generally sound like obvious B-sides, even though actual Radiohead B-sides have generally sounded like A-sides. If the aim is to offer a little perspective into the musical background of the two centerpiece albums, “Kid A Mnesia” delivers, but not impressively. There are much more compelling supplements, such as the documentary film “Meeting People Is Easy.” The most puzzling aspect of all might be why Radiohead condoned a lukewarm presentation with so much hype. It should be noted that Thom Yorke initially intended to title 2003’s “Hail to the Thief” “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” but was prohibited by record labels. At any rate, “Kid A” and “Amnesia” are two seismic releases that are as life-affirming when consumed together as when taken in separately. The albums still reverberate with the force and feeling that brought popular music to a standstill, and ultimately nudged it slightly further out.

“Kid A Mnesia”releases Nov. 5 on Apple Music.