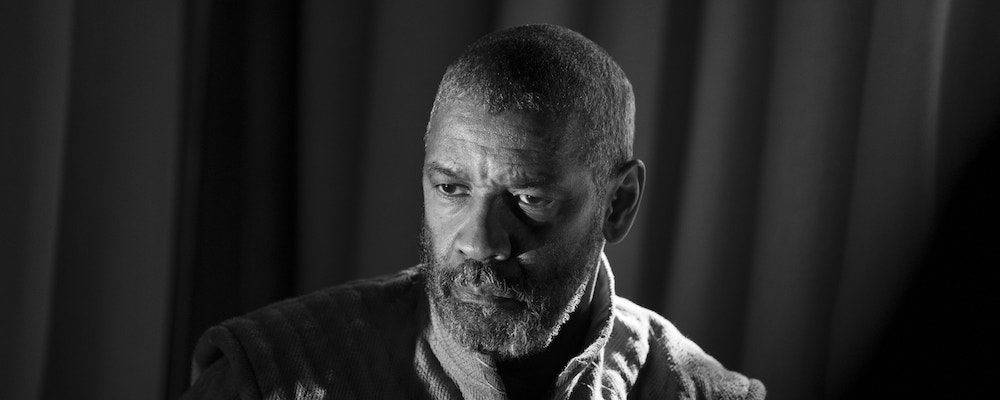

‘The Tragedy of Macbeth’: Denzel Washington and Frances McDormand Bring Sound and Fury to Joel Coen’s Rich Shakespeare Adaptation

Alci Rengifo

For decades, film and stage have demonstrated that if William Shakespeare were alive today, he would undoubtedly be the world’s most in-demand playwright and screenwriter. There is not a single genre that has not borrowed something from the greatest playwright to ever dip quill in ink. It makes absolute sense then, that Joel Coen makes “The Tragedy of Macbeth” as a medieval noir. Whispered only as “The Scottish Play” by theater artists convinced the work is cursed, it is a Shakespeare tragedy that gets typically staged as political allegory. Macbeth’s lust for power and string of killings could be superimposed on any tyrannical regime anywhere. Coen decides to focus on another, equally unnerving side of the play. His Macbeth is out of a true crime story, not thinking through an impulsive act that turns him into a cornered fugitive, chased by shadows within shrinking hallways.

Although the play is over 400 years old, some may still not know the basics. Macbeth (Denzel Washington) is a Scottish general, Thane of Glamis, who achieves praise from King Duncan (Brendan Gleeson) after fighting off the Norwegians and Irish. Soon after battle, Macbeth and fellow fighter Banquo (Bertie Carvel) come across a Witch (Kathryn Hunter), who splits into three and prophesizes that Macbeth will be king. This sets off a devious air not only in the general, but also his wife, Lady Macbeth (Frances McDormand). They hatch a plot to kill Duncan when the king visits their home to spend the night. Macbeth wanders into his chambers and stabs the doomed monarch. Now proclaimed king, Macbeth has to scheme even more to protect his throne. More murder follows as Duncan’s actual heir, Malcolm (Harry Melling), becomes a target and marshals forces to take on the usurper. As they cling to power, the Macbeths also descend into their own vortex of guilt and madness.

Becoming acquainted with the great works of Shakespeare can also mean diving into a cinema universe all its own when it comes to adaptations. The best ones always find a way to make the material new again while bringing out what is so timeless about the text. “Macbeth” is Shakespeare’s shortest tragedy and has made for some visceral filmmaking. There’s the 1948 version by Orson Welles with its rugged production design, Roman Polanski’s brilliantly savage 1971 take and recently in 2015, Justin Kurzel made a visually stunning “Macbeth” with a haunted performance by Marion Cotillard as Lady Macbeth. Coen’s adaptation proves again this material just never gets old. He emphasizes the power of the language by creating an immersive experience that isn’t always about being ferociously loud, although when needed the film does reach intense heights. The cinematography is by Bruno Delbonnel, who has lensed previous films famously made by Coen and his brother Ethan (this is Joel’s first solo credit as director) such as “Inside Llewyn Davis” and “The Ballad of Buster Scruggs.” Delbonnel films Macbeth’s world as some kind of enclosed, expressionist dreamscape in clean black and white. There’s not too much of the real rust and grit of other medieval films, instead there are long shadows, bubbling surfaces with mist and night skies dotted with twinkling stars.

This is a magnificent visual approach because Coen, as in the films made with his brother, is focusing on the characters and what’s ticking inside of them. Performance is of course key in Shakespeare and Denzel Washington and Frances McDormand are a choice both keen but also unique. Typically the leads in this play are cast much younger to emphasize the youthful drive to power. By making Macbeth and Lady Macbeth over middle age, Coen turns the narrative into something even more tragically moving. These are not two inexperienced upstarts, but seasoned figures aware they’re crossing the Rubicon and possibly sealing their fates. If one is still looking for allegories, think of a Gaddafi stubbornly exercising brutal power before the end of his ossified reign, or older convicts who still somehow stumbled into a horrific set of choices late in life. Lady Macbeth schemes and utters, “Come, thick night, and pall thee in the dunnest smoke of hell, that my keen knife see not the wound it makes, nor heaven peep through the blanket of the dark, to cry ‘Hold, hold!’” McDormand plays the moment like someone who has been waiting for their big break too long in life and is now ready to do anything.

Denzel Washington also brings something new to a role that has been inhabited by so many great modern actors. His Macbeth is not quick to rage but instead stops to think, reflecting on where his decisions are taking him. Other actors like to give the doomed false king a touch of madness, but Washington would rather make him sad. This Macbeth is not a driven young beast hungry for power, but an older man who felt the Witch’s prophecy finally opened a door he could walk through and has to live with the consequences. When Lady Macbeth meets her end, Washington stares at her body, delivering the famous soliloquy that includes, “It is a tale, told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.” He delivers the lines knowing this was always a probability. Under Coen’s direction, this line could be applied to any true crime case where we’re left wondering how anyone, especially seemingly ordinary people, could have become embroiled in actions so heinous.

Coen’s selection of the key supporting roles is on par with Washington and McDormand. Kathryn Hunter, an acclaimed veteran of the theater, plays the Witches with a contorting, unnerving presence. She turns the characters into an otherworldly specter. Corey Hawkins as Macduff, Thane of Fife and eventually Macbeth’s great rival, has the more thunderous presence in terms of delivery. Hawkins is so good you can easily seem him cast as Macbeth in a more traditional production. The entire cast feels and understands the language, which is also essential to making a Shakespeare adaptation have renewed urgency. By casting Black Americans in key roles, Coen captures the transcendental power of timeless language as well. There is a reason why Shakespeare has been staged in nearly every corner of the globe, with different communities finding something in the Bard’s stories that connects to them.

Joel Coen is first of all a film director and he still stages scenes of pure cinematic excitement. When Macduff’s son is killed it is staged in a striking, fiery sequence where the child is literally tossed into the raging furnace of a burning house. The sequence where Macbeth follows a knife he sees in his mind, down a hall on his way to commit to a murder, is also imagined with one of the year’s best uses of production design (pay attention to the door). And at 1 hour and 45 minutes, “The Tragedy of Macbeth” is a reminder that Shakespeare can somehow still be more suspenseful than the typical, three-hour behemoths we are served weekly at the movie theaters. Draped in dark corners and driven by cursed psyches, “The Tragedy of Macbeth” is a purely absorbing experience, as it should be, and will continue to be as more artists will continue finding bloody meaning in its words.

“The Tragedy of Macbeth” releases Dec. 25 in select theaters and begins streaming Jan. 14 on Apple TV+.