‘Who We Are: A Chronicle of Racism in America’ Urgently Confronts America’s History and Ongoing Inequality

Alci Rengifo

To say that the United States was founded on white supremacy might seem like an intensely loaded statement for some. “Who We Are: A Chronicle of Racism in America” convincingly argues that it’s a very accurate statement. Surprisingly enough, the presentation that forms the core of this documentary took place on Juneteenth 2018, two years before a wave of mass protests and social reckonings that followed in the wake of George Floyd’s death. However, by then Black Lives Matter had already been making an impact following other enraging acts of police brutality, and what attorney Jeffery Robinson has to say has gained even more relevance. He is a Black American presenting evidence to make a case for why history matters.

Robinson, a former ACLU Deputy Legal Director, delivers his meticulous talk on the long history of race relations in the U.S. at the Town Hall Theater in New York City. He’s an engaging speaker with the air of a welcoming college professor. Robinson begins with his memories of being a young boy in Memphis during the turmoil of the 1960s. For Robinson the 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. marks a tragic tipping point where the great social changes propelled by the civil rights movement began to roll back. The memory has the powerful personal touch that Robinson and his father marched with King days before the murder. It is as if every time America comes close to a real breakthrough the old roots of the nation crawl back up to strangle hope. The same thing happened soon after the Civil War when Reconstruction was halted and the South slid into the Jim Crow era of violent segregation. Robinson then combines history with personal testimony to demonstrate the long road to where we are now. He begins with the first slaves in Jamestown, proceeds through events like the 1921 Tulsa Massacre and his recollections of watching his parents attempt to navigate Memphis’s racist culture to ensure their kids a better future.

Some of the major historical events Robinson recounts have been explored many times before, like the gruesome murder of Emmett Till or the impact of D.W. Griffith’s 1915 silent epic “The Birth of a Nation,” which helped revive the appeal of the Ku Klux Klan. What Robinson does so well and urgently is dissect other corners of official American history to expose a parallel racial history more unsettling to discuss. He confronts attempts to claim the Civil War was not really about slavery with documents and statements demonstrating that slavery was at the core of the conflict. Yes, there was a deep economic factor in the southern oligarchy not wanting to be taxed, but such grievances were to protect wealth they could only generate through slavery. Robinson has to make this point to Confederate flag wavers in Charleston, South Carolina, one of whom admits he wouldn’t want to be a slave in “modern times.” As for those who complain about proposals for reparations over slavery, Robinson points out that Abraham Lincoln gave Washington slave-owners hefty reparations for freeing their slaves. The system has always had a colonial-racist vein, going back to how slave patrols were the first real police forces in the country.

Directors Emily Kunstler and Sarah Kunstler, who are the daughters of Chicago 7 attorney William Kunstler, make the smart choice of giving “Who We Are” good momentum by cutting away from the Town Hall lecture to follow Robinson to historical sites or places that hold personal memories. The lecture information is impactful and eye-opening, but would feel too sluggish without breaks in tone. Robinson visits the Old Slave Mart Museum in Charleston where we hear the chilling details of how humans were once auctioned in chains. The museum director points out fingerprints on the walls from slaves who laid the bricks of not only the museum’s building, but of buildings all over the city, if not the nation. In New York City Robinson gazes at the New York Cotton Exchange, as another historian explains how the country’s center of capitalist commerce was once a spot to also sell Black slaves. Insurance policies were put on people, even those who did not make the hellish boat ride from Africa to American shores. Robinson also speaks with “Mother” Lessie Benningfield Randle, who at 107 is the last surviving witness to the Tulsa Massacre. It is endearing and rightfully disturbing to see Randle recall the carnage she viewed, when white mobs found an excuse to crush Black prosperity.

To be a Black American is to feel the weight of all this history, but Robinson wants viewers to understand this is a collective history as well. It would be insane to automatically tag any white person as racist, what Robinson wants to dig into is the social infrastructure of the nation that has always granted a specific racial group who colonized the continent power over a sector of the population that arrived as slaves. It is ignorant to deny how the past still casts a shadow and trickles down to us. Robinson shows how our much glorified Constitution quickly made sure slavery couldn’t be challenged. Article V blocked any amendments until 1808. Even the Star-Spangled Banner had a violently racist passage removed from the final version. Its lyricist, Francis Scott Key, was a lawyer who prosecuted those accused of peddling abolitionist literature. Robinson also doesn’t pretend to be a partisan liberal. He gives a blistering takedown of Bill Clinton’s 1994 Crime Bill, which only helped further criminalize Black American youth. The spike in incarceration rates as a result cannot be denied.

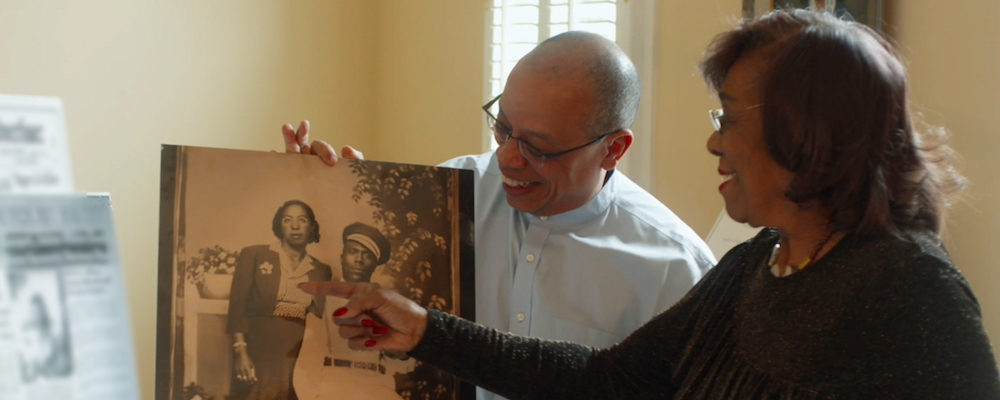

While Robinson also sits down with some moving and powerful subjects for the camera, such as the mother Eric Garner, some of the more striking non-lecture sections belong to his own memories. He returns to the Catholic school he attended as a boy in Memphis, sitting down with two white childhood friends who recall the plight of just wanting to play basketball at a local gym together. Robinson considers himself lucky for having parents who were willing to find a way to move their family into a suburban neighborhood so their sons could have better opportunities. Even this memory is tinged with disturbing details, like the neighbor who brought over cookies but quickly turned away when she realized the new family moving in was Black. Such moments further propel Robinson’s presentation, because they go to a truth we all need to be aware of as citizens. The past is not dead and influences the now. At a time when inequality and social unrest feel like incoming thunder across this nation, Robinson’s history lesson is a needed look at where we’re coming from and where we keep going.

“Who We Are: A Chronicle of Racism in America” releases Jan. 14 in select theaters.