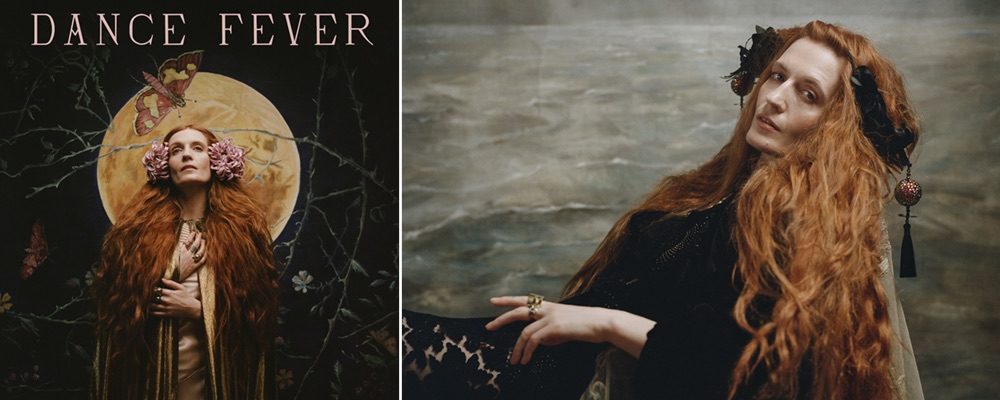

Florence and the Machine Harness the Power of ‘Dance Fever’

Adi Mehta

“Dance Fever,” the latest album from UK indie giants Florence and the Machine, drew its titular inspiration from the phenomenon of choreomania, a mysterious “dancing plague” that took over Europe in 1518, whereby hordes of people, sometimes numbering thousands, took to dancing erratically in the streets until the point of exhaustion or injury. Despite its “plague” terminology, the topic came to fascinate frontwoman Florence Welch before the onset of the pandemic, appealing to her background as a dancer and the sort of delirious, liberating revelry she has found in dancing. The latest album finds Welch confronting her anxieties, fate, and the supernatural, overcoming the spirit-crushing dictates of the pandemic, and soaring triumphantly in the face of everything. The new material is everything we have come to expect from Welch and crew — dark, theatrical, soulful, inspirational, anthemic.

On a track titled “Choreomania,” Welch does justice to the intensity of the inspiration she finds in dancing, as she loses herself in a handclap slatter, marveling, “Suddenly, I’m dancing to imaginary music / I’m freaking out in the middle of the street / With the complete conviction of someone who has never actually had anything really bad happen to them.” The same idea informs “Free,” which finds Welch specifically confronting her anxieties and looking to the power of dance to free herself. She laments, “It picks me up, puts me down / A hundred times a day,” but eventually musters up the resolve that is the album’s overall resonant cry, bellowing her worries away, and declaring in a swift swoop from her grounding, immersive cadences, “ And for a moment, when I’m dancing / I am free.”

The struggle to unleash and express oneself is a recurrent topic. On “Girls Against God,” Welch vividly resists fated, gendered circumscriptions of fragility, jeering, “It’s so good to be alive / Crying into cereal at midnight,” then lashing out, “But oh, God, you’re gonna get it / You’ll be sorry that you messed with us.” Of course, there is no shortage of aggressive music propelled by outbursts of righteous indignation, but Welch’s choice to present her frustration more subtly here sets the song apart, with her restrained delivery capturing the struggle to find the voice that eventually booms. Gentle guitar strumming gives way to distant operatic voicings, and a mobilizing ditty emerges in choral harmonies, as if arising from a shared public sentiment, brought by Welch to an anthemic realization.

Welch, who has spoken about the seemingly spiritual sensation that overcomes her during live performance, toys with ideas of the otherworldly. “Heaven Is Here” is a vaguely witchy, handclap-led chant, with Welch hooting and hollering, rolling her r’s. in sprightly, erratic swooshes and sweeps in a way that recalls a bit of “The Dreaming”-era Kate Bush. “Dream Girl Evil” is a standout from the moment of Welch’s soulful opening bars. The track moves to a devilish strut, like an initiation rite of sorts, with inverted gospel outpourings and a general ritualistic sense about it. Welch sings the title in a shuttering snarl, dons a close, intimate voice for the verse, and ultimately bellows at stadium proportions. The track captures her at her most epic, illustrating everything that makes her a larger-than-life figure.

As the world became constrained in lockdowns, and Welch found herself increasingly turning to dance for catharsis, the choreomania reference came to inform the overall designs of the new album. “Cassandra” finds Welch struggling to find inspiration in the still bleakness of the pandemic, reflecting, “I used to see the future and now I see nothing.” The sparing musical elements are all purposely employed — fleeting choral swells, percussive accents, the ubiquitous, ethereal backing vocals, and Welch’s dramatic episode plays out in real time, as the track unravels into haunting, wordless melodies, over which Welch speaks seductively, evoking countless, charged gothic precedents, before building to another sweeping chorus. “My Love” zeroes in on Welch’s lone voice as it rises and triggers the drop of a string-laden electronic dance beat. Considering the album’s focus on the power of dance, the added edge and immediacy of such percussive stylings further realizes the angst and catharsis to which Welch keeps referring. As Welch recalls, “My arms emptied, the skies emptied / The billboards emptied,” we get a sense of the apocalyptic scale amid which such songs came together, making the stream of grand sonic gestures ring grander yet.

Interspersed among the central thematic threads are a few compelling loose ends. Brief interludes frame and add dramatic edge to the album’s central story. “Restraint” features Welch’s raspy strained utterance of a sole question, “Have I ever learned restraint?” over a tortuous backdrop built from the reversed audio of breaths. The jilting shuffle of “The Bomb” begins in a serene singsong, in which Welch’s emotional whims color her utterances as she works her way through her melodies, building to a momentous admission of “I don’t love you / I just love the bomb.” The grounding closing number, “Morning Elvis,” draws out warily from the flurry in a country-informed haze of tremolo guitars, as Welch recalls an ill-fated Graceland visit in a reflection upon her struggles with sobriety.

The album’s central statement is expounded in the lead sing and opening number, “King,” a song about learning to embrace life’s tragedy in order to achieve its triumph. It’s a sentiment succinctly reaffirmed in the percussion-less “Back In Town,” in which Welch confirms, “I came for the pleasure, but… I stayed for the pain,” as subdued choirs spill out gradually from beneath her. A statement of such pomp and promise is ideally suited for Welch’s dramatic bent and flair, and one that only the rare voice as powerful as hers can project in all its potency. In “King,” Welch builds gradually, over an elegantly spacious sonic backdrop, driven by propulsive, resounding drums. Her delivery is full of emotional nuances that translate into musical heft, as she grunts, winces, and forces out words, escalates to an uninhibited, soaring declaration, “I am no mother, I am no bride, I am king,” then jettisons words altogether in a climactic belt. “Daffodil,” a standout track, finds Welch having seized control and found her way through the pandemic, beaming with rapturous abandon. The soprano voicings that weave their way through her melodies are especially captivating, and Welch’s breathy pronouncement of the titular word itself makes the song.

Interestingly, Welch has cited her confidently simple refrain of “Daffodil” as an instance that made her check her impulses and question her sanity. Luckily, she ultimately dared to follow her muse. A gripping beat and ominous drone carry us through the creeping, twisted romp of “Daffodil” to a brutal, plodding finale that is, by far, the album’s most thrilling moment, one that evokes all the drama of Welch raging against God. To answer a question she herself posed, Welch almost definitely learned restraint, but also learned when to be unconcerned with it. To this latter lesson, we owe all the grandeur by which we know Florence and the Machine, and which “Dance Fever” captures in the most epic fashion. The album is a celebration of Welch’s shackles relinquishing their grip under the force of her howling voice, of the oppressive forces, in this world and others, yielding to her autonomy, as realized in the rapturous, liberating power of dance and music.

“Dance Fever” releases May 13 on Apple Music.