‘Little Richard: I Am Everything’ Captures the Conflicted Life and Legacy of a Rock ‘n’ Roll Pioneer

Adi Mehta

The roots of rock ‘n’ roll have always belonged to its Black pioneers, but Little Richard was an important figure who went largely unrecognized throughout his life. Filmmaker Lisa Cortés’ new documentary, “Little Richard: I Am Everything,” chronicles Little Richard’s conflicted life and celebrates his creative legacy, leaving behind an inspirational portrait that delivers on the hyperbole of its title, as it links disparate embodiments of rock ‘n’ roll to its well-deserving subject.

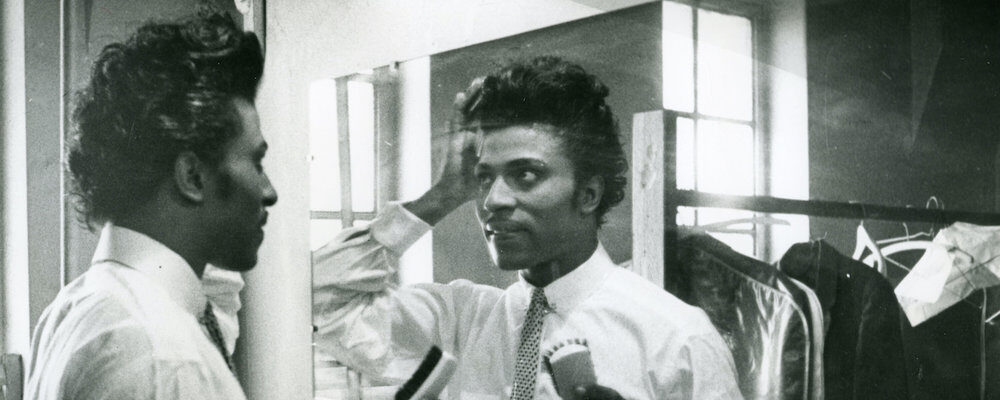

“I Am Everything” relies primarily on the usual rock doc means of talking heads, archival content, celebrity montages. It begins with footage of Little Richard that showcases his trademark style and unique persona. Celebrities like Mick Jagger and Tom Jones share their impressions. Among the other voices who offer a running commentary is sociologist Zandria Robinson, who makes bold statements like, “The South is the home of all things queer.” Little Richard’s queerness was of a particularly Southern strain. His flamboyance comes with a gospel-like fervor that “I Am Everything” quickly traces to his roots in Macon, Georgia, where life revolved around the church. Black-and-white footage of Richard’s childhood, interspersed with the colorful excesses of his adult life, remind us simultaneously how much and how little has changed.

Cortés looks back to Richard’s inspirations, like Sister Rosetta Thorpe. There are flashes of Black women who sang “dirty blues… with gold-plated teeth.” A snippet of Lucille Bogan’s 1933 song “Shave ‘Em Dry” begins with, “I got nipples on my titties.” We follow Little Richard on his first tour with a troupe named in one newspaper reel as “Florida Blossoms Minstrels,” then learn of a character Little Richard played called “Princess Lavonne,” and find, surprisingly, that minstrel shows and drag shows overlapped. We learn of Esquerita, the queer Black artist who taught Little Richard to play piano, and of Billy Wright, who sported “pancake makeup,” and a pencil mustache, and helped Little Richard get his first record deal.

The film takes us behind the stories of Little Richard’s greatest hits. “Tutti Frutti” was born when Little Richard took to the piano after attempts to make him sing like Ray Charles and B.B. King had failed to impress. We hear the song’s original lyrics. “Tutti Frutti, good booty / If it don’t fit, don’t force it.” In a flash, a sanitized version of the song takes the country by storm. Footage from both performances and interviews capture Little Richard’s infectious energy.

Cortés gives plenty of historical perspective. Black music was still considered “race music,” but Little Richard benefitted from the rise of independent DJs and transistor radios. The idea of the “teenager,” as distinct from the child, only emerged in the 1950s, and youth across race lines found a thrill in Little Richard’s novel, subversive rock ‘n’ roll. As John Waters, who still dons his pencil mustache as tribute to Little Richard, recalls, “Even racists loved Black music in teenage Baltimore.”

Record labels, however, didn’t value Black creators. A young Little Richard wound up being paid half a cent per record, while Elvis Presley and Pat Boone capitalized on “Tutti Frutti.” One snippet reveals an introduction of Pat Boone as the man who made it a hit.” Still, Little Richard produced an impressive string of hits. “Long Tall Sally” turned the tempo up and became a gold record.

As Little Richard attests, “My music broke down the walls of segregation.” While predecessors like Fats Domino had been unthreatening, Little Richard gyrated and sang coded descriptions of graphic sex at the same time Emma Till was lynched. The band was run out of towns and Little Richard was thrown in jail for walking around with long hair. Critics were quick to blame rock ‘n’ roll on the devil, a charge with which even Little Richard came to agree.

Much of the documentary focuses on the ambivalence that characterized Little Richard’s life. After surviving a rough flight and thinking god spoke to him, Little Richard turned to religion. We hear firsthand accounts of when he enrolled in Alabama’s Oakwood University and said he would buy his records back from people to throw into a bonfire. He married a woman, forswore rock ‘n’ roll and took refuge in the gospel. But, he relapsed. We see him now standing on pianos, taking off clothes, outdoing his earlier excesses. By now, the music had spread to Britain, as Little Richard had become the idol of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. Paul McCartney credits Little Richard for all his “screaming numbers,” while Mick Jagger credits him for his stage moves. By 1974, his rockstar lifestyle had intensified. In interview segments, Little Richard admits to a life full of orgies and cocaine. When the death of his brother, Tony, triggered a second attempt at salvation, Little Richard renounced homosexuality. He spent years doing church events and gospel shows, even selling bibles, but struggled to earn a living. He inched closer to his older music without reaching.

We see modesty eventually give way to resentment. Little Richard called himself the “architect of rock ‘n’ roll,” pointing out that he had come out before Elvis. Richard was finally recognized by the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, but died in 2020, before the ceremony. Later in Little Richard’s life, more people had begun to appreciate his legacy. Cortés treats us to footage of a teary-eyed Little Richard accepting the American Music Award of Merit in 1997. Keith Richards recalls the Stones’ tour with Little Richard and claims, “I probably learned more in those six weeks than I ever have, before or since.” Bowie tells him, “Thank you for creating rock music, the greatest art form of the 20th century.”

In the end, we’re left with a portrait of an artist who was ahead of his time, yet simultaneously held back by it. Near the end, Sir Lady Jane, a member of Little Richard’s close circle and a prominent voice over the course of the film, admits that gays felt betrayed by Little Richard, but simultaneously credits the artist for giving her the courage to perform in drag. It’s notable that Sir Lady Jane appears in the film convincingly dressed as a woman. The mix of Little Richard’s contemporaries and younger voices on display allows for a multi-dimensional study, while the collected footage showcases a personality that needs no embellishment. Galactic metaphors and matching visual effects throughout might be a bit much, but “I Am Everything” carries them. The weakest link is a the couple of reenactments with actors playing Little Richard. They are not particularly convincing and break the flow. Otherwise, everything else is in its right place.

In a late interview segment, we find Little Richard seeming to approach some enlightenment. He turns down an offer to choose between his music and virtue, instead claiming, “I think all of that goes together.” This statement resonates on multiple levels, as the musical and social landscapes of today assume a more congruous form in the light of Little Richard’s influence.

“Little Richard: I Am Everything” releases April 21 in select theaters and VOD.