‘Rock Hudson: All That Heaven Allowed’ Movingly Chronicles the Screen Legend’s Closeted Life

Alci Rengifo

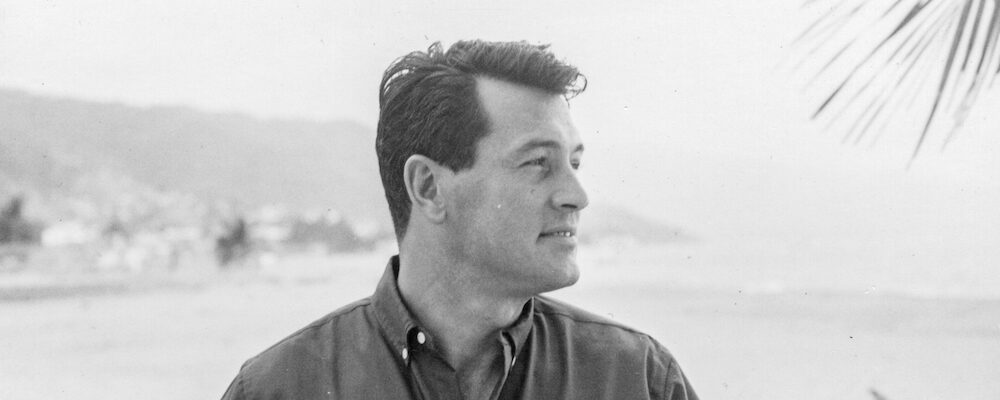

For a long time now the image of Rock Hudson has evoked a dual portrait of the Hollywood dream. He rose to stardom as the definition of the handsome leading man, defining American masculinity as it was standardized in the 1950s. He died in 1985 of AIDS, shocking millions with the subsequent revelation that he had been a gay man all his life. The legacy Hudson would leave behind would be a sad clarion call for the urgent need to confront the epidemic, and also a reflection on one of the biggest of all movie stars who was forced to live his life in hiding. “Rock Hudson: All That Heaven Allowed” is a brisk new HBO documentary by Stephen Kijak that will best serve those who are unaware of Hudson’s story, while providing a moving interpretation for those familiar with the details. By the end, Hudson’s journey takes on bittersweet dimensions that are haunting.

The key source is Mark Griffin’s 2019 biography of the actor which is the same name of the documentary. Griffin narrates much of the story over photos, private films, newsreel footage and other sources edited together into an immersive collage. Much of the beginning is the biographical details chronicling how Hudson, born Harold Scherer Jr., left his home state of Illinois as a young man who had served in World War II. He wanted to be an actor, despite having no formal training. He would make connections in the gay community, first through a major DJ which would lead to a road that would take him to Henry Wilson, a power player agent who was also in the closet. It was Wilson who would build the persona of Rock Hudson out of Scherer, getting him those first parts that would establish him as a Hollywood leading man. Yet Hudson would always find himself wearing different masks, with only certain perfect roles seeming to let him express who he truly was.

Kijak gets this idea across quite effectively by selecting certain clips from Hudson roles to underline ideas and commentary. In “Giant” he personifies the ultimate American male ideal, rugged, brave and in the end standing against prejudice. Other, earlier roles were too obsessed with his good looks to the point of casting him in juvenile parts that seemed out of place for the tall, butch Adonis. It would take German émigré Douglas Sirk, one of the great masters of melodrama, to bring out the subtler side of Hudson in great films like “Magnificent Obsession” and “All that Heaven Allows,” which used technicolor richness to comment on the darker side of American suburbia. There are entertaining behind-the-scenes revelations thrown around by other commentators, such as Hudson not getting along with James Dean on the set of “Giant.” Dean resented Hudson’s hetero-posturing in public while hitting on him behind closed doors. As for Hudson, nearly all agree he was that rare, genuinely nice person in Hollywood. Former boyfriend Lee Garlington describes a very generous lover who was absolute fun to be with. Garlington also shares rare photographs taken during his time with Hudson that are moving to see. One photo finds the pair in New Orleans during a vacation outing in the 1960s, which was quickly kept hidden.

For every dreamily nostalgic memory or image, “All That Heaven Allowed” then counters with the more unsettling realities of such a different time in American society. In an era when government agencies openly refused to hire homosexuals, to be outed in pop culture could mean the instant death of a career. Kijak devotes an insightful section to the evolution of masculinity in media following World War II, when the leading men of the silent era and 1930s were replaced by muscled fantasies modeled on the militarized spirit of the war years. Marlon Brando, Kirk Douglas and Hudson would define the new look, with Hudson becoming a major sex symbol for the white picket fence Eisenhower decade. Somehow even the tabloids, which were the sole den of raunchy speculation at the time, passed over Hudson (Wilson reportedly sacrificed another client by outing him in order to divert attention). A striking example of how far agents could go is Hudson’s marriage to Phyllis Gates, Wilson’s secretary. It’s confirmed in the documentary to have been nothing more than a scheme by Wilson to silence suspicions, especially when Hudson was nearing 30 and remained a bachelor. But Gates was clearly left emotionally damaged and for Hudson it was also not an easy façade to sustain for nearly four years.

It’s astounding to see how Hudson remained a positive, by all accounts, stable person despite all the pressure and deception. Consider roles like “Pillow Talk,” where Hudson plays a character pretending to be gay. Such storylines were pushed by producer Ross Hunter, also in the closet, to brush away gossip since no one would suspect Hudson of openly flaunting such a secret in a movie. In John Frankenheimer’s “Seconds,” you can see the sense of tense release in how Hudson delivers lines about living a double life. Though possibly his best performance, the thriller was not a hit with a populace who just wanted to see him as a romantic leading man. In private Hudson would enjoy the perks of his success with travel, fun and countless affairs with other men. A phone recording features a conversation where a studio figure offers Hudson the chance to meet a promising new young talent. Hudson asks about their “equipment” before agreeing to meet.

Hudson could have never imagined in his glory days how his life would end as a powerful revelation and statement. Interview subjects recall those frightening early days of the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s, when so many in the gay community were infected and died. The Reagan White House and its right-wing agenda didn’t care and carried on in a deadly ignorance. Hudson kept working after being diagnosed, appearing in the show “Dynasty” clearly too thin and ill in his late 50s. Co-star Linda Evans remembers an infamous kissing scene, realizing later Hudson kept risking botching the scene by continuously doing takes with his lips closed. Aware he was infected, he was trying to protect her at a time when paranoia ran deep about how the disease was transmitted. Then there are the infuriating details of Hudson falling mortally ill in Paris, with the hospital where he stayed insisting he leave when his condition was made public. Hudson’s former assistant reveals she had to rent a 747 to take him home to Los Angeles when airliners refused to carry an AIDS patient.

Hudson’s illness and death galvanized friends like Elizabeth Taylor to take a more active role in combating AIDS, but in a broader sense it was also a needed crack in America’s fantasies about itself. A supreme idol of onscreen masculinity turned out to be gay, and it changed nothing about the quality of the movies and those great roles. The prejudices that forced Hudson, and so many others, to live double lives were confirmed again to be so idiotic. Sadly, despite all the progress made, we still live in a country of many prejudices aimed so squarely at the LGBTQ+ community. That’s why a documentary like this deserves to be seen. One can certainly critique some of Kijak’s editing choices, particularly in how the first half is mostly narration and the second introduced on-camera interviews. But it’s an absorbing portrait of a legendary actor and his true self, contrasted with how post-war America wanted to see him as a channeling of an ideal that was always pure mirage.

“Rock Hudson: All that Heaven Allowed” airs June 28 at 9 pm. ET on HBO.