‘Psycho: The Lost Tapes of Ed Gein’ Is a Tongue-in-Cheek Peek Into the Mind of a Notorious Killer

Tony Sokol

If ever there was a notorious character worthy of sensational coverage, it is Ed Gein. The 1957 execution of Albert “The Lord High Executioner” Anastasia barely got noticed outside of New York City papers and radio reports. The body of the 3-to-6-year-old “Boy in the Box” found in Philadelphia similarly made the city papers that year, but the Wisconsin killer was on the headline of every newspaper in the entire country, and the cover of “Life” magazine. MGM+’s “Psycho: The Lost Tapes of Ed Gein” strives for the kind of sensationalism reserved for true murderous icons. Director James Buddy Day and his team certainly have bragging rights, a newly unearthed only-existing-recording of Gein himself, which this documentary series hypes to the very edge of unintentional spoof.

Every episode opens with a warning saying what we are about to see is not for the faint of heart. “We’re not kidding,” we read. As each episode delves deeper into the findings on the tapes, the opening amends the cautionary notification to add how the current installment will be worse than the last. This is great salesmanship, but it is also funny. The docuseries leaves plenty of room for chuckles after dropping serious details of a tortured mind.

Each opening also includes short cuts of the most graphic content to be taken by police photographers when entering Gein’s Plainfield, Wisconsin farmhouse of horrors. There are three or four which make the big hit list: The full naked torso of Bernice Worden, one of the two women in their 50s killed by Gein. Worden’s rib cage had been split and her body was hollowed and “dressed out” like a deer. Her torso is headless.

The head of Mary Hogan was found in a box, and also makes regular appearances. The rest of the recurring images come from assorted gruesome talismans Gein assembled from the remains of the estimated 15 bodies he dug up from a nearby cemetery. As a killer and grave robber, Gein is unique because he repurposed body parts, one of the experts says. The documentary is very generous with his creations, like skull soup bowls and ashtrays, furniture made from human bones, lampshades from preserved faces, a human skin apron and gloves, and a full wearable female body suit.

We get to see these images quite often, but they come most prominently after the warnings, and are followed by reminders of “don’t say we didn’t warn you.” In most cases, the majority of viewers would roll their eyes after the images made too many appearances, but “The Lost Tapes of Ed Gein” keeps them entertaining. That is subversive, which could also describe the effect of the initial media coverage of the Gein killings in the 1950s.

As the documentary points out, the U.S. was a naïve place in the post-war era. Or at least it projected an innocent face of white picket fences, first-run “The Donna Reed Show” episodes, and traditional values, especially in middle America. Gein shocked the country with irreconcilable mystery. In-the-know commentators, hungry for every rumor to be proved, dive into Gein’s early life, making vastly provocative assumptions and passing them off as psychological theory. One expert admits he knows little about Gein’s relationship with his mother, but implies any kind of debauchery is open for discussion. The documentary reinterprets Gein’s fetish for the anatomy found in medical encyclopedias, and his collection of pulp horror novels and porn magazines.

The experts believe Gein was trying to recreate his mother, Augusta. They speak of incantations at her gravesite in hopes of resurrecting the body. The viewer can picture Gein as not just the monster, but a budding Frankenstein, digging up decaying female corpses in the graveyard, dissecting heads, saving sex organs, livers, hearts, intestines, and genitalia. A dissatisfied Gein moved on to fresher victims who were his mother’s age. Mary Hogan disappeared from her tavern in December of 1954. Bernice Worden, who ran a hardware store, disappeared in November of 1957. Her son Frank, the sheriff’s deputy, is the officer who suggested checking Gein’s farmhouse and the adjacent woodshed, attached by a door. The doc also notes that Gein confessed being unable to dig his mother out, and how the town did not allow the exhumation of Augusta Gein’s body.

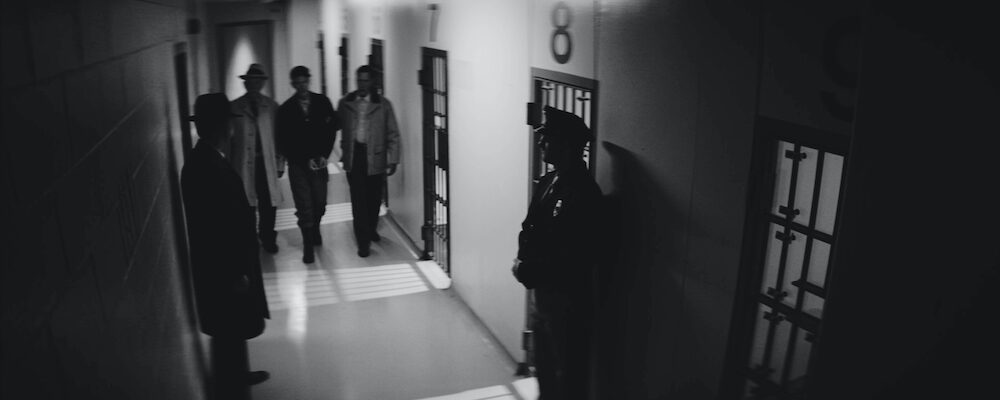

At the center is the never-before-heard jailhouse recordings of Gein. Ed says he can’t remember how many people he actually killed. He gives the same answer when asked if he enjoyed committing the crimes. His voice is alarming at first, his answers too short, affirming or denying specific details. Gein puts no emotion behind the words, as one of the experts says, he treats it like “any other day.” The documentary is right to point out the chilling effects of his emotional distance.

Gein gives simple explanations, and only vague motivations for the desecrations. He is also led by the questioning police officer, who is trying to assist and translate what he is hearing, not guide or undermine the confession. We hear helpful suggestions which could only be made by someone who knew the kind of life people live in that small, poor community. Gein is asked if the cutting of the human bodies is like cutting deer or other game meat. This isn’t intended to lead the suspect, but rather to establish ground language for communication. Still, we wonder what the more impromptu explanations might be.

“The term serial killer didn’t come out until 20 or 30 years after Gein was caught,” says Dr. Jooyoung Lee, serial homicide researcher at the University of Toronto. But Ed Gein was not specifically a serial killer. He suffered some kind of psychosis. He killed two women and robbed graves. The first in-depth work on Gein’s crimes was found in Robert Bloch’s novel “Psycho,” which was only based on the midwestern recluse, not a retelling.

Three classic horror characters are based on Geins: Norman Bates in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 premiere psychological thriller “Psycho;” Leatherface in Tobe Hooper’s 1973 groundbreaking chiller “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre;” and Buffalo Bill in Jonathan Demme’s 1991 killer gamechanger “Silence of the Lambs.” They are all sensational movies. “Psycho: The Lost Tapes of Ed Gein” tries to match the sensationalism. It perfectly suits the needs of fans of true crime who can pick apart the details and come up with their own conclusions.

“Psycho: The Lost Tapes of Ed Gein” begins streaming Sept. 17 on MGM+.