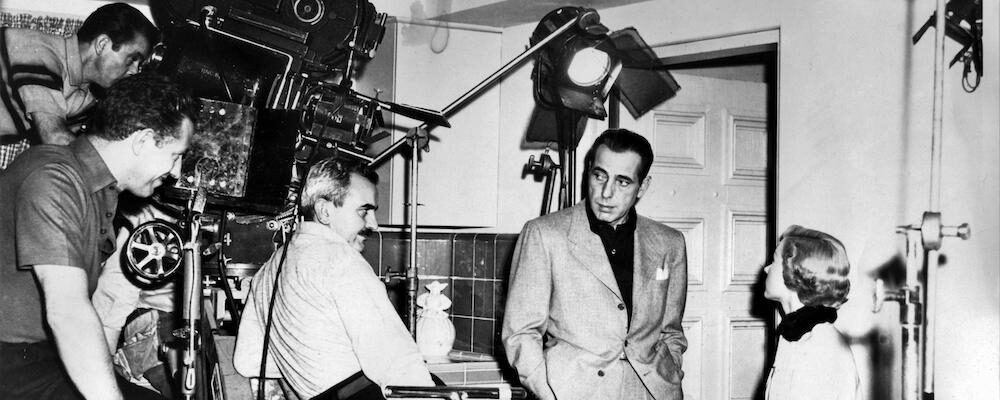

‘Bogart: Life Comes In Flashes’ Frames Its Telling of a Hollywood Legend Through the Women He Loved

Tony Sokol

One of the biggest stars of Hollywood’s Golden Age was its least likely, and most critical, known for bashing the phoniness of celebrity and the film industry’s most egregious creative offenses. The best thing about “Bogart: Life Comes In Flashes,” the first official feature documentary on Humphrey Bogart, is that all of the narration comes from public quotes directly attributable to the source. As Warner Brothers’ most bankable performer, the star of “Dead End,” “The Maltese Falcon,” “Casablanca,” and “Caine Mutiny” gave dozens of interviews, including extensive talks with biographers, never mincing words, the tools of Bogart’s trade. Director Kathryn Ferguson solves this dichotomy by centering on Bogart’s most exclusive inner circle.

Bogart once told Frank Sinatra, “The only thing you owe the public is a good performance,” and this documentary delivers on the promise. “Bogart: Life Comes In Flashes” highlights magnificent acting chops, but tells Bogart’s story through the women that were beside the screen legend. Bogart’s mother, the famed illustrator Maud Humphrey, and his four wives: esteemed Broadway stage performers, Helen Menken and Mary Philips; fading screen and stage character actor with dangerously paranoid aim, Mayo Methot, and the young protégé of Howard Hawks, Lauren Bacall. Each influenced Bogart’s artistic ambition, and often the actor’s political and social sensibilities.

Bogart’s independent stature looms large in almost every genre, and evokes ridicule or confoundment in others, such as his turn as a vampire in “The Return of Dr. X.” Yet the persona lives an enduring cinematic life of its own. Bogie is a major character in the Woody Allen play and film “Play It Again Sam,” signifying the importance of the multi-level personality to any age. Ferguson’s personal twist puts the feature in its own documentarian stratosphere.

In his trench coat, fedora, and immaculate suit, speaking in a thick, aggressive New York City accent, Bogart embodies the quintessential American image of masculinity, whether playing an anti-hero, reluctant or broken hero, or unrepentant villain. Ferguson focuses on the impact of the strong women who shaped the evolving actor. This invites new perspectives of the art and artist.

Each relationship brings fresh insight into the arc of the main player. Bogart’s first two wives provide theatrical lessons which last long after the curtain falls. Methot teaches Bogart how to cover up knife wounds, and still make a morning call to assigned shoots. Relaxing outings on Bogart’s boat, Santana, merit warnings to coastal patrols, even as “The Battling Bogarts” act together in “Marked Woman.” These former cinematic footnotes are examined to reveal astonishing achievements, and masterful controversies. One of these, Helen Menken’s timely theatrical run-in with Mae West, is as fascinating as any Bogart revelation. This is true even for readers of Darwin Porter’s gossipy speculative tell-all-and-then-some “The Secret Life of Bogart,” which purported to report such fracases on a blow-by-blow basis.

A major highlight is the vastly diverse eras which are explored. Bogart’s theatrical career corresponds with Jazz Age Broadway, and his rise to the top of Tinseltown occurs during the Golden Age of Hollywood. The period excitement leaks into this film, best when delivered in the oral tradition by Louise Brooks, who not only acted on the same stages and soundstages, but wrote some raucously hilarious books on the players. While Brooks is very expressive about Bogart’s expansive pre-fame reputation and disreputable pursuits, it is obvious this documentary keeps things clean.

Dispelling myths for the casual follower, “Life Comes In Flashes” shows Bogart’s life through major cultural shifts. He was born well-to-do, with a successful doctor for a father, and a voting rights activist mother, famous in her own right in the magazine publishing field. The former “Maud Humphrey Baby,” as he was known throughout the nation on Mellon’s Food baby food packaging, rebels with and without cause. Bogart is evicted from one prestigious academy after another until enlisting in the Navy, not by the patriotic call to fight in World War I, but to avoid his angry father. Bogart worked steadily in theaters through the Great Depression, and was an eyewitness to increasing and insidious threats of censorship: from the Broadway plays of the 1920s, encroaching further through production codes of the 1930s, onto the communist witch hunts of the 1940s. Bogart’s role in the Committee for the First Amendment is another highlight, the pressure to distance himself from the protest is heartbreaking, even if downplayed.

Bogart remains one the most influential figures in the art of acting, some of this is lost on producers, and even family members committed to upholding accepted canon. “Life Comes In Flashes” quotes Bogart as not caring for the “scratch your ass and mumble” style of method actors. But he worked well with such cast members, and courted Marlon Brando for a lead in Bogart’s independently-produced “Knock on Any Door.” Bogart turned in method performances on film before any actor, other than John Garfield. Fans of Bogart and classic Hollywood cinema will enjoy “Bogart: Life Comes In Flashes” immensely. Newcomers to Old Hollywood history will be struck by the similarities and discrepancies of the times.

“Bogart: Life Comes In Flashes” releases Nov. 15 in in select theaters.