‘One to One: John & Yoko’ Promotes Immediacy Over Nostalgia for an Intimate Portrait of Artists in Flux

Tony Sokol

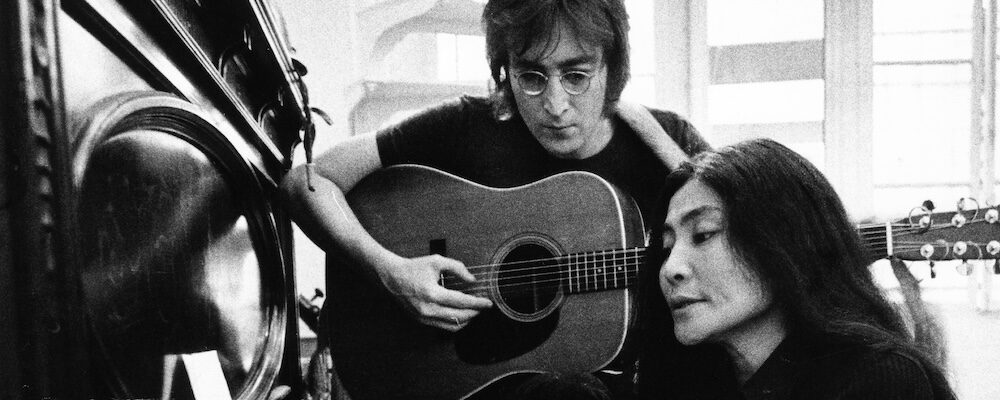

Kevin Macdonald’s “One to One: John & Yoko” is an emotionally rich recounting of what led to the two concerts John Lennon and Yoko Ono performed with the Plastic Ono Elephant’s Memory Band on Aug. 30, 1972 at Madison Square Garden. It’s no oldies show, nor a nostalgic blast from the past. Issues may have changed, but the songs resonate with new meaning. The benefit for the embattled Willowbrook State School was Lennon’s first full-length concert since the Beatles’ 1966 Candlestick Park performance, and is not presented in full. The meat of the story is in the evolution of the journey.

“One to One: John & Yoko” highlights the storytelling prowess of Scottish director Kevin Macdonald, who helmed the award-winning feature “The Last King of Scotland.” Expertly edited by Sam Rice-Edwards, the feature-length documentary is held together thematically by repeated flipping through American television channels during the early 1970s. The documentary pits changes in the medium’s treatment of current events against Lennon and Ono’s acclimation to life as immigrant New Yorkers. Early on, an interviewer catches Lennon enthusing over the chance to relax and watch American TV. The ex-Beatle knows the power of television in the country firsthand. His band became an overnight sensation throughout the U.S because of the historic “The Ed Sullivan Show” broadcasts.

“One to One: John & Yoko” sits on a very Beatles-cartoon-worthy arc about Lennon’s initial freedom from voracious British post-Beatlemania, and the negative media bombardment aimed at Ono. Intimately shot archive footage allows Macdonald to keep the camera steady on the eye of the storm. Lennon, comfortable in the position since being the navigator of the British invasion, proceeds with undistracted purpose, and nonchalant body language. Ono, thrust into the spotlight with callous abandon, turns that negatively-charged lightning rod into continued reminders of the gender bias at its heart.

Archival recordings underscore how Ono is forced to fight on more fronts than her “radical rock star” husband. Ono’s interpretations of what unites the oppression of women, immigrants, Blacks, the poor, prisoners, and mothers are fierce and measured. Besides evoking deep empathy for personal trauma, Ono’s ongoing efforts to reunite with her kidnapped daughter Kyoko fuels the overall drive for effective idealism.

The timeline begins when Lennon and Ono are escaping British fame and settling into a two-room loft at 105 Bank Street in Greenwich Village “to live like students,” in August 1971. While not quite “Barefoot in the Park,” the couple’s first apartment comes with colorfully idiosyncratic personalities. New York City is one of those characters. Other players come from the “radical left” element which greet the pair upon arrival. These introductions are joyous and hopeful, but “One to One” is not without suspense.

The Nixon administration’s contagious paranoia creeps insidiously into the cinematic consciousness after a string of successful and satisfying protest performances catch the eyes of the authorities. Lennon is threatened with deportation for a five-year-old marijuana plea. Previously unheard phone conversations, recorded by Lennon in the event future legal defense requires proof, provide brief but illuminating snatches of off-the-cuff solutions to a myriad of problems. The black and white transcriptions do not diminish the impact. The taming of activist, and Bob Dylan’s personal “garbologist,” A.J. Weberman is as dramatic in audio as any confrontation in motion picture features. The darkness of the activist’s conversation is ironically softened by the cinema verité of real captured recordings. A deft touch.

The self-surveillance audio also provides insight into the artists’ intent, and ongoing adaptability to circumstances. One taped discussion overhears Lennon repeatedly offering the song “Attica State” to be performed at the John Sinclair Freedom Rally. A voice on the other end struggles to hide an increasing reluctance to the overtly suggestive and controversial addition. Activist John Sinclair was sentenced to ten years on a drug charge, this wasn’t his first conviction, and the additional song, promoting the idea to “free all prisoners, everywhere,” could be seen as further antagonism.

Lennon comes across as no less antagonistic than the cheeky Beatles’ personal history, and mythology, paint him. “John Sinclair” remains the song of the demonstration, while “Attica State” is also performed, but becomes an unnamed mission statement for the Free the People tour. This brings substantial personal and political depth to both the film, and the many directions attempted as an ongoing tour goal.

The abuse and neglect suffered at the Willowbrook State School comes out of the blue, through a televised exposé from Geraldo Rivera. Ono, hit hardest, appears to find the neediest cause the musicians can aid immediately. A concert can successfully fix one small social problem, tangibly. “One to One” puts the idea out there, without excessive force.

The live footage provides the power. The remasters of producer Phil Spector’s original ad-hoc recordings bring the concert to life. The live footage is clear, clean, propulsive, and sonically edited to allow the aggressive power of the instruments and voices wide range. The band sounds fierce, at times almost punk. With occasional nods to the supporting musicians, the laser focus is on John and Yoko. The concert is not fully presented, and some songs serve as informative counterpoint to the continuing narrative. “New York City” accompanies John and Yoko’s arrival, “Cold Turkey” represents the agony of Nixon’s reelection. The integration works emotionally, and the song placements retain relevance throughout.

“One to One: John & Yoko” is arresting and tight, with an extremely relatable loose feel. There is also ample room for small comic moments and running gags, such as an ongoing effort to procure flies for an experimental film to be directed by Ono. Lennon’s self-deprecating humor is up front at all times, but most especially on stage. He calls out his own mistakes, and adds comically impromptu interpretations of well-known lyrics. This does not diminish the power of the performances, and Macdonald’s focus exposes the raw nerve at play.

With “One to One: John & Yoko,” Macdonald mines the relevancy of a 50-year-old performance for tools against similar challenges currently facing political art. Most of the views espoused on the tour buses, hotels, and music and TV studios still ring fresh in a climate of divisive tribal faith-based opposition. “One to One: John & Yoko” finds the artists reflecting underground beliefs which came to define modern cultural exchange, now under attack. Macdonald’s underplayed revolutionary subtext feeds the vibrancy of contemporary concerns. It is also a must-see for Lennon and Ono fans, especially completists. The feature documentary plays in the mind’s ear long after the curtains fall, and is not limited to the performance.

“One to One: John & Yoko” releases April 11 in iMAX theaters.