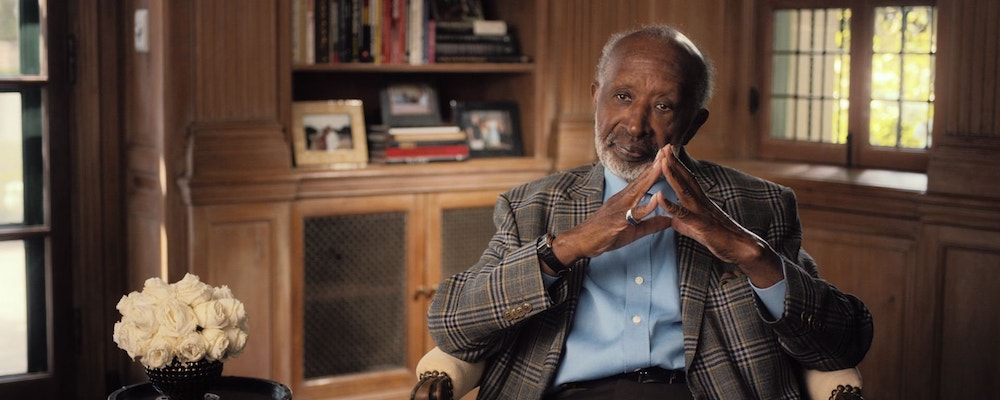

‘The Black Godfather’ Tells the Story of Behind-The-Scenes Mastermind Clarence Avant

Adi Mehta

Director Reginald Hudlin explores the truly extraordinary life and achievements of the behind-the-scenes music executive, entrepreneur, influencer, and mentor Clarence Avant in his informative, entertaining, and profoundly inspirational documentary “The Black Godfather.” The film is filled with accounts from friends and colleagues of Avant’s, always speaking with the utmost conviction. Now 88 and retired, Avant was a businessman of the highest rank, which is worth celebrating on its own. But add to this that he was a black man in a time when racism was not just a fringe ideology, but the default mindset. He managed to defy all preconceptions with nothing more than his forthrightness and charisma, winning over anyone with rationale and compassion, leading the way for a myriad artists of diverse musical backgrounds, and setting an example for the triumph of human ingenuity over superficial distinctions. It’s well past due that the world learns about his genius.

A series of talking heads drop accolades in the beginning, calling Avant things like “the celebrity’s celebrity.” Even Barack Obama shows up numerous times. When it comes his turn, Avant himself is asked about being called a “godfather,” and answers, with characteristic bluntness, “People have called me a son of a bitch. So what? That’s part of life.” A snippet like this effectively gets to the root of the matter — the particular qualities that made Avant so special.

The film takes you way back to the end of Prohibition. Avant absorbed the appeal of speakeasy culture, and mined it for a wealth that earned back its value many times over. Industry pioneer and mogul Quincy Jones is one of many recurring contributors, recounting long lost stories. Three-time Emmy Award winning actress Cicely Tyson speaks with passion and awe about first seeing Avant walking out of a midtown New York building, dressed to the nines, walking with purpose. After this adulatory description, which could otherwise be dismissed as mere crushy fodder, she adds with gusto, “and he was this color,” while pointing to her own face.

Hudlin takes us through the process by which Avant eventually created his own record label “Sussex,” a name he chose by combining the words “success” and “sex.” Always going against the grain and playing by his own rules, Avant signed guitarist Dennis Coffey as his first artist. Coffey instantly shot up to number one on the black charts, when black DJ’s learned he was white, and freaked out. Avant’s daughter Nicole fondly recalls her father’s reaction when confronted about the issue, quoting him: “Who gives a shit what he is? It’s music.” Nicole goes on to detail Avant’s promotion of musician Sixto Rodriguez, who was banned in apartheid South Africa, but eventually became an enormous success with his film “Searching For Sugar Man.” Among the biggest talents that Avant introduced to the world was Bill Withers, who didn’t fit the mold of the typical black artist of the times, looking more like a folk singer than an R&B act. Yet, we all know his hits “Ain’t No Sunshine” and “Lean On Me” today. Avant took chances, and trusted his instincts, and it nearly always paid off.

The film shows clips from the groundbreaking show “Soul Train,” which gave most of white America its first look at undiluted African American culture. People had never seen such fluid movement and such rhythmic instinct, and the nation became transfixed. In a typical, unethical business move, Dick Clark, creator of the show “American Bandstand,” tried to rip off Soul Train by pitching a rival program, “Soul Unlimited.” Clark offered Avant a generous sum to promote the show, but Avant, ever the ethical citizen, refused, and even threatened to get people on the streets. ABC did not move forward with the show. We can see the example Avant set followed years later in the admirable actions of Dave Chapelle, who was offered a deal by FOX under the condition that he included more white people in his show. To this condition, Chapelle pointed to the network’s numerous shows with no black people, and walked out of the meeting.

As pivotal as the Civil Right Movement was, it can be misrepresented by many of today’s misguided youth. Middle class kids become hipsters and scream obscenities in the streets to no avail, when they could easily lobby senators and have a far greater chance of accomplishing their goals. Clarence Avant was busy making money, and the degree of respect shown him from blacks and whites alike was itself proof that racism was not exactly an insurmountable barrier. When civil rights leader Danny Blakewell reached out to him, Avant characteristically responded, “I don’t wanna talk to no damn civil rights group. I’m sick of these niggas,” and hung up the phone. Later, however, when Blakewell specified, “We have to stop standing on the sidelines,” Avant rejoined, “I like that. That’s what I’m all about.”

When Avant did get involved in civil rights, he did it his own way. He organized a five-day music festival, bringing together the three biggest black labels, Motown, Stax, and Atlantic Records, all on one stage. Sammy Davis Jr. was shunned by the black community because of a picture in which he was hugging President Nixon, but Avant convinced the audience to give him a chance. In one of the film’s most compelling scenes, Davis confronts a booing crowd, saying, “Disagree, if you will, with my politics, but I will not allow anyone to take away the fact that I am black.” Immediately, the crowd erupts into crazed applause, whereupon Davis performs, “I Gotta Be Me.” In the end, the entire stadium is filled with smiling faces, and Davis looks like he is about to break into tears.

Having grown up in Climax, North Carolina, where the KKK ran rampant, Avant knows what it was like to be black in the south. When African American Andrew Young tried to run for congress in 1970s’ Georgia, Avant called him crazy, but went on to say, “If you crazy enough to run, I’m crazy enough to try to help you.” Of course, the campaign was a success. Today the word “racist” gets thrown around so carelessly that it often ceases to have any real meaning. Hudlin’s film puts things into perspective, with segments that will surely teach clueless social justice warriors a thing or two.

Avant convinced football Jom Brown to venture into film, a move that proved historically monumental, with an interracial love scene with Raquel Welsh that landed Brown plenty threats, but didn’t deter him from continuing to challenge conventions. When black baseball star Hank Aaron was on the verge of breaking Babe Ruth’s 714 record, he received no shortage of hate mail. The camera zooms in on some of the letters, reading the likes of “Dear Hank Aaron, Retire or DIE!!” Here, you have people who are so desperate to cling on to an idea of racial superiority that they are willing to threaten death rather than face the reality that they were wrong all along. The sheer level of idiocy is astounding, and it’s one of the film’s most epic moments when Aaron finally breaks the record. An announcer exclaims, “A black man is getting a standing ovation in the deep south, and it is a great moment for all of us.”

The movie takes us into the low points too. We see how Avant created “Avant Garde Broadcasting Inc.” Radio, but eventually the IRS snatched everything, and padlocked the radio station. Avant couldn’t pay Bill Withers, and his house was in foreclosure. However, all his friends came to the rescue, and he ended up just fine. We see a friend of Avant’s talk of how he “saved my marriage, saved my life,” and of how he went on to name one of his twins Clarence. Avant eventually gets behind Michael Jackson’s “Bad Tour,” and gathers crowds bigger than those for Springsteen, Genesis and Madonna. He arranges an epic Muhammad Ali TV Special. The list goes on.

It’s easy to simplify history into a neat dichotomy that confirms readily to the storybook narrative that we’ve come to expect over the years. The truth of the matter, however, is that this narrative is outrageously reductive, and fails to recognize the contributions of unsung heroes and open-minded thinkers on both sides of the equation. It goes without saying that our historical past was a prejudiced, bigoted nightmare. What few realize, however, is the considerable number of talents who defied all odds against them, and were so readily accepted into the popular cannon that their outsider status has long ceased to even be a matter of consideration. The most recurring comments from the assemblage of Avant’s associates, among them Sean Puffy Combs, Lionel Ritchie, Jamie Foxx, and Bill Clinton, reveal how Avant was, underneath all his bluff and bluster, a consistently honest, decent guy who balanced his thirst for grandeur with a principled commitment to helping out his fellow man in a way that was never exploitative. He’s described as having “that something where he can connect with everyone.” When asked about his success, Avant humbly explains, “I don’t know how I got involved with anything. I just took shots.”

“The Back Godfather” begins streaming June 7 on Netflix.