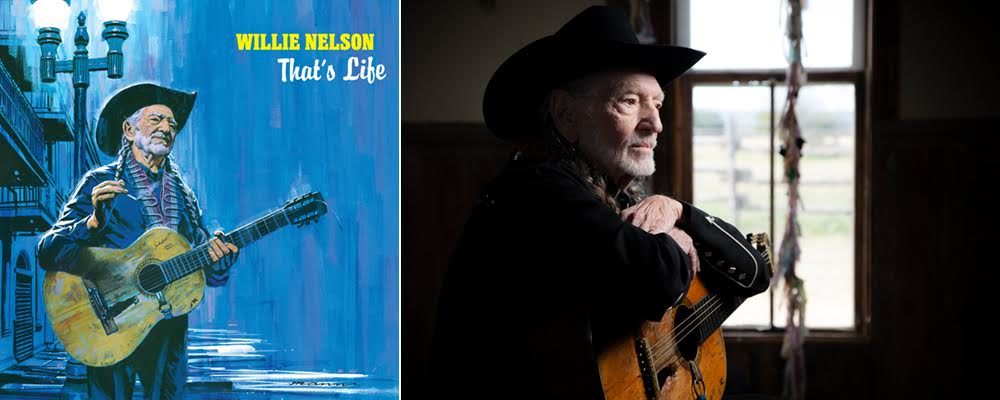

Willie Nelson Explores Some Deeper Cuts on His Second Sinatra Tribute ‘That’s Life’

Todd Gilchrist

After releasing the Frank Sinatra tribute album “My Way” in 2018, Willie Nelson returns with “That’s Life,” a second collection of songs from Ol’ Blue Eyes’ expansive catalog, and more broadly, celebrating the durability of the Great American Songbook. Where the first record felt like a roundup of all-timers — featuring “Fly Me to the Moon,” “It Was a Very Good Year” and “My Way” — this one gets into some second-tier (but no less great) classics and even a few songs that would qualify as deep cuts, or at least are less well known outside of Sinatra’s fan base. Set against some elegant orchestral arrangements and a few ornamental nods to Nelson’s country roots, the 87-year-old’s effortless, unfussy delivery simultaneously honors Sinatra as a forbear, industry colleague and former friend, and gives these songs new life without merely reproducing the elements that made them standards in the first place.

“That’s Life” seems like a particularly fitting title for Nelson’s seventy-first solo studio album, looking back on a career and life as everything from a country outlaw to political activist, with some legal entanglements and movie roles (and much more) in between. The more recognizable songs he performs here feel like a bit of a clearinghouse after “My Way,” including “I’ve Got You Under My Skin,” “You Make Me Feel So Young” and “Luck Be a Lady,” but that shouldn’t be mistaken as Nelson phoning anything in; rather, they provide connective tissue between Sinatra’s looming iconography and songs presumably chosen because they more directly tap into the scrappy country spirit that has long been a cornerstone of Nelson’s art. Opening with “Nice Work if You Can Get it” and closing with “Lonesome Road,” Nelson charts a path through Sinatra’s career, exposing digressions that greatest-hits packages fail to touch on, and highlighting unexpected overlaps between the two artists.

Nelson handles the material brilliantly, working with producers Buddy Cannon and Matt Rollings and engineer Al Schmitt to build intimate, small-scale orchestral arrangements that showcase his voice, and then add in slightly anachronistic instruments such as a slide guitar or harmonica that work like a signature. His performance of a song like “Just In Time” (first performed by Sinatra in 1959 on “Come Dance With Me!”), for example, feels tailor-made for the first dance at a wedding, or opening-credits music for a Nora Ephron-style rom-com — the sweet punctuation to a long-awaited romantic connection. But then he juxtaposes it with “Cottage For Sale,” from “No One Cares,” a record Sinatra supposedly called a collection of “suicide songs,” and Nelson conveys all of the melancholy of his predecessor’s version, just without the musical luxuriance.

Sinatra, of course, regularly moved through different song cycles, vacillating from swinging party records to more introspective fare, testing out different collaborators on the page and in the studio, and over the span of a more than a 60-year career, he had the space and versatility to do so. In condensing his tributes to two albums, Nelson by necessity must make some of these seemingly discordant transitions. But the record’s musical unity smooths over any tonal speedbumps, and anyway, his voice kind of always sounds a little bit joyful, and a little bit wistful — and perfectly appropriate for Sinatra’s songbook.

If the studio polish seems a little constrictive on “I’ve Got You Under My Skin,” a signature song for Sinatra that he recorded multiple times throughout his career, including famously live at the Sands Casino with Count Basie, Nelson rebounds nicely on “You Make Me Feel So Young,” a song first performed during Sinatra’s heyday but sounds more appropriate coming out of an older performer’s mouth. When Nelson sings, “You and I are just like a couple of tots,” you believe it more from a man rediscovering his joie de vivre at an advanced age even than Sinatra, who recorded his version at 40; and after he pauses for a harmonica solo, you get this sense of different styles and generations colliding in a wonderful, delicate, perfectly synchronous way. He then duets on “I Won’t Dance” with Diana Krall, who gives a velvety performance that you could easily imagine pairing with Sinatra on one of his “Duets” projects; Nelson doesn’t quite embody the song’s fleet-footed spontaneity, but it feels like a joyous collaboration nonetheless.

Again, the title track is a standout, and Nelson could possibly carry it forward as a standard of his own, if he didn’t have so many to draw upon already. “Luck Be A Lady” is similarly vibrant, and Nelson keeps up with an agile, lush orchestral arrangement. But it’s his version of “In The Wee Small Hours of the Morning,” from Sinatra’s album of the same name, that he quietly devastates the listener, adding layers of loss, regret and age to what was already a poignant ode to heartbreak. But the one-two punch of “Learnin’ The Blues” and “Lonesome Road” brings together these disparate threads as the record comes to a close, finding a harmonious middle ground between country music’s aptitude for poetic sadness and big band jazz’s irrepressible exuberance.

Nelson knows he doesn’t have to go for broke, even on the real swinging numbers, and simply inflects the familiar lyrics to these songs with a sense of wry, learned joy that’s more sweet than bitter. But as he sings to “seek your maker / before Gabriel blows his horn” on “Lonesome Road,” he unearths the gospel, and African-American folk tradition that gave all of this music its foundations, as he makes a beautiful plea for perseverance not just in spite of failure and shortcoming, but because of it. A record like this could easily be a victory lap or cash-in for a venerated artist like Nelson, but “That’s Life” suggests he’s trying to challenge himself as much as celebrate these songs — “pick yourself up and get back in the race,” so to speak, even though their quality and consistency reiterate that he never left.

“That’s Life” releases Feb. 26 on Apple Music.