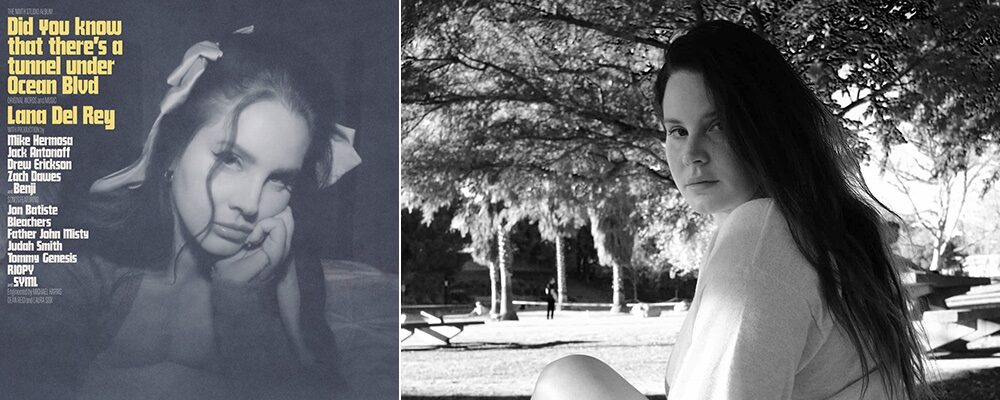

Lana Del Rey Hovers Between Heaven and Hotel Room Floors on ‘Did You Know That There’s a Tunnel Under Ocean Blvd’

Adi Mehta

Lana Del Rey has always offered a unique mix of nostalgia and novelty. Modes and manners of bygone eras came alongside hip-hop-style grandstanding in crafted pop songs that often took inspiration from Old Hollywood opulence. After 2019’s “Norman Fucking Rockwell,” Del Rey reformulated the blend, looking more to the lores of both suburban and rural Americas and the folk sensibilities of singer-songwriter traditions, straying from her pop confines to chart a freer range in freer forms. The aesthetic shift that began on 2021’s “Chemtrails Over the Country Club” continues with Del Rey’s latest album, “Did You Know That There’s a Tunnel Under Ocean Blvd.” This time, deeper introspection is the focus, and the songs are as wordy, whimsical and unconventional as the title suggests.

There is indeed a tunnel under Ocean Boulevard. Jergins Tunnel was built in 1927 for the safe passage of pedestrians to beaches, but closed to the public in 1967. A former landmark once widely celebrated for its beauty has been ejected from the general collective consciousness. Del Rey poses the eponymous question on the album’s title track, as she worries that the total of her life’s work might vanish as easily as this tunnel did. The thought of the site makes her confront her legacy and reflect upon her net contribution, while also offering an escape fantasy, an end to the tragedy in which the central figure was “Born to Die.”

From the onset, the lines blur between Elizabeth Grant and Lana Del Rey. The 2020 and 2021 deaths of her cousin and grandmother left Grant hyperconscious of her own mortality. This prompted the existential reflection that unfolds in multiple threads over the course of the album. We find Del Rey reevaluating the goals and accomplishments of her life. While she insists that her coping experience left her with a new perspective, her attempts to make sense of fate and family end in continued ambivalence. When it comes to her creative choices, however, she hardly flinches.

“Ocean Blvd’s” opening track, “The Grants,” refers to several members of the family, including her late uncle, David Grant, who died in 2016 while climbing the Colorado Rockies. The track might have seemed an interesting choice for the “Ocean Blvd’s” third single, but it’s a natural opener, informing the entire album. “I’m gonna take mine of you with me / Like ‘Rocky Mountain High,’ the way John Denver sings,” is an early instance of the great lengths to which Del Rey goes to communicate nuances. The refrain is about bringing select memories with her to an afterlife. You can do this according to her megachurch pastor, Judah Smith. Unfortunately, we have to listen to him on one of the album’s interludes that sets his evangelical-style buffoonery to piano, with Del Rey occasionally chiming in. The “John Batiste Interlude” takes a similar behind-the-scenes approach, but spares us the cringey sermoning, as Batiste immerses himself in his music and lets out erratic, impassioned exclamations. Batiste brings a level of musicianship that elevates the album and also contributes to “Candy Necklace,” one of “Ocean Blvd’s” catchier tunes in which numerous themes converge.

Del Rey finds herself torn between the calls of a ticking biological clock and the open wounds of her troubled romantic past. On “The Grants,” she sings, “You’re a family man, but / Do you think about heaven?” On “Sweet,” further questions are, “Do you want children? Do you wanna marry me?” Among the contemplations of “Fingertips,” she considers, “It’s said that my mind / Is not fit, or so they said, to carry a child / I guess I’ll be fine.” By her own account, Del Rey is always the other woman in her relationships. She has tried to embrace this role with varying results. She dismissed moral objectors on “Ultraviolence’s” “Sad Girl,” singing, “Being a mistress on the side / It might not appeal to fools like you.” On the video for “Paradise’s” “Ride,” she stated, “I was born to be the other woman / Who belonged to no one / Who belonged to everyone.” This is echoed in “A&W,” when Del Rey says, “I say I live in Rosemead,” in a sole voice, then multiplies into a chorus to add, “Really, I’m at the Ramada.” She goes on to recall encounters that race to ends “on the hotel floor.” The song’s meter could have made for a satisfying conclusion from just the following line: “It’s not about havin’ someone to love me anymorе.” Yet, Del Rey goes further and fits the song to its title: “This is the experiеnce of being an American whore.”

“A&W” is the album’s greatest departure and greatest triumph. Two songs, as different in their structures and sounds as in their sentiments, somehow make for a gestalt. In part two, a familiar haze of whispers and wispy melodies takes a radical turn when electronic drums emerge. A steady plod comes with a whirl of effects. The unpredictability of the song’s arrangement makes for a thrilling experience. At moments, the dancy detail of the percussion recalls the work of Atoms For Peace and growling synth bass approaches the likes of Portishead’s “Third.” We end up somewhere entirely different with sharp focus and blaring volume. A twisted, witchy jam ensues as Del Rey reduces her lyrics to varied repetitions of “Jimmy, Jimmy, cocoa puff, Jimmy, Jimmy, ride.” She models it after the refrain of Little Anthony and the Imperials’ 1967 song, “Shimmy, Shimmy, Ko-Ko-Bop,” about a man’s entrancement by an exotic woman. The Del Rey deviation comes with a drug reference and continues with “Jimmy only love me when he wanna get high.” Again, we find Del Rey playing a disposable part in a dissipation that accounts for senses more than sentiments.

In “Kintsugi,” Del Rey finds validation for Leonard Cohen’s “Anthem” in the eponymous style of Japanese pottery, pulling from Cohen’s famous lyrics, “There is a crack, a crack in everything / That’s how the light gets in.” This calls for a song of its own, “Let the Light In,” which offers a brief relief from the album’s nebulous soundscapes by delving into vintage stylings reminiscent of the Laurel Canyon music scene. Yet, the titular declaration falls short of its revelatory ring. Del Rey calls it out in the chorus as she makes her way through the “backdoor” to visit a previous paramour, played by Father John Misty. A deceptively light singsong that places the pair in harmony belies a relapse to the seedy escapades of “A&W.”

Still, Del Rey is a believer, not only in the heaven of Hollywood megachurches, but the classic ideal of love. She’s happy for those who find it — like her recurrent producer Jack Antonoff and his fiance Margaret Qualley. “Margaret” imagines a song for their wedding, in the form of rosy rom-com fare with Antonoff himself throwing in a bit of the album’s overall quirk. And, while Del Rey hasn’t found lasting love, the piano waltz of “Paris, Texas” makes light of the plight. Del Rey reminisces, “I went to Paris,” in melodies fit for smitten stumbles on picturesque Parisian streets, before hastily whispering “Texas.”

Del Rey’s bold choices on “Ocean Blvd” make for a truly original and unsettling album, as we survey the depths of Del Rey’s desperation. “Ocean Blvd’s” subdued, depressive soundscapes are full of odd amusements, with some memorable thrills, such as in “Fishtail,” with Del Rey repeating, “You wanted me sadder,” reminding us that she is sick of being reduced to a tortured soul. There are also some missteps. Take the album’s following track, “Peppers,” in which Del Rey boasts, “Me and my boyfriend listen to the Chili Peppers / We write hit songs without tryin’ / Like all the time.” This is a hit only in the sense of an assault on “Ocean Blvd.” Juvenile repetitions of “Hands on your knees / I’m Angelina Jolie” come in a rapped chorus, sampled from Tommy Genesis’ 2015 track “Angelina.” While hip-hop has long been a key component of Del Rey’s sound, and frivolous lyrics have balanced dark subject matter, the sample is only tolerable under the guise of irony. Here, Del Rey might be a bit too confident about her instincts. Still, she remains resolute. Del Rey concludes the album with “Taco Truck x VB,” a trap-informed rework of “Venice Bitch” from “Norman Fucking Rockwell.” After all her reflection, she appears content with the world she has created. She dishes out more of her most divisive fare, as she laughs in the faces of critics and gossip queens.

“Did You Know That There’s a Tunnel Under Ocean Blvd” releases March 24 on Apple Music.