‘Wormwood’ Blends Drama and Documentary to Tell Dark Story of Drugs and the CIA

Alci Rengifo

Distorted reality, fractured memories and the dark heart of American history form the core of “Wormwood.” A grand, six-part miniseries, it is the first Netflix production directed by legendary chronicler Errol Morris. A filmmaker who will find fascination in any subject, Morris’s films have ranged from the absurdly interesting to pieces of absolute historical importance. “Wormwood” takes a bit from all of his obsessions to weave a disturbing, haunting tapestry about the most underground aspects of the Cold War. It tells the story of Frank Olson, who in 1953 fell to his death from the tenth floor of a New York hotel. For years it was believed Olson was the tragic victim of a CIA experiment involving LSD, his death being the result of a “bad trip.” But of course the passage of time has revealed there’s more to the story, and Morris uses the Olson case to tell a wider narrative about the victims of history. This is also Morris’s first attempt at finding a parallel balance between dramatic filmmaking and documentary, intercutting drama with real life testimonials in a way that creates an engrossing effect.

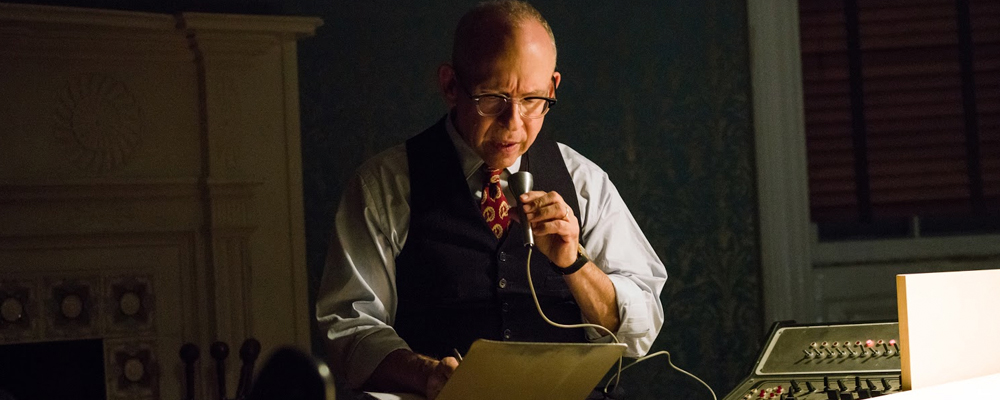

The miniseries’ main character is Eric Olson, who talks with Morris about his hazy memories from the 1950s as a child growing up in Fort Detrick, where his father Frank Olson (played by Peter Sarsgaard) worked as a scientist researching biological weapons for the military. Eric is himself considered a brilliant man, but he has squandered any pathways towards a major career because of the obsessive drive to get answers as to why his father fell to his death in 1953. The nightmare apparently began on November 18, 1953 when Frank Olson and some colleagues met with CIA officers at the Deer Creek Lodge in the mountains of western Maryland. According to the government’s findings, Olson and another colleague were given a dose of LSD in their drinks and were told as much by a present CIA doctor named Sidney Gottlieb (Tim Blake Nelson ). The dose was part of the agency’s infamous MK-ULTRA program, which sought to explore various forms of mind control aimed at spies. After the meeting in the cabin, Olson reportedly displayed behavior typical of a mental breakdown and as the days and weeks passed he made strange claims, asked to be fired to his superiors and found himself supervised by military handlers. Olson’s strange and disturbing odyssey culminated in a stay at the Statler-Hilton in New York, accompanied by fellow guinea pig Richard Lashbrook. Lashbrook would claim that he awoke to find Olson diving out the window.

The approach Morris uses to weave the intricate tapestry of this series is a brilliant amalgam of real interviews and dramatic recreations. Eric Olson himself sits in front of the camera, his face haunted by time and obsession, while Peter Sarsgaard plays the doomed Frank Olson in dramatic sections filmed in noir textures. “Wormwood” as envisioned by Morris is chronicle, nightmare and powerful scrapbook of memories. The room from which Olson jumped serves as a starting point to travel into the more disturbing America that always existed beneath the conservative ethos of the post-World War II world. There is a hallucinatory edge to the visuals, especially a recurring image of Olsen standing in a lake, waving his arms into the water, transfixed either by the drug he has taken or the sense of a life becoming ever more surreal. Morris imagines the final moments in the hotel in “Rashomon” style, with different variations on how Olson could have been pushed or forced out the window. Two ominous figures in coats and fedoras represent CIA agents sent to do the job. Contrasted with this, film clips of Eric’s infancy, cradled by his parents, take on an ominous tone as he realizes his white picket fence life was all illusion.

Like all great documentary filmmakers, Morris is an absorbing storyteller. “Wormwood” develops like a thriller, what we believe to be the truth in the first episode suddenly reveals itself as a lie by the third and so on. Was Olson really given LSD? Or did he uncover disturbing truths about the U.S. and chemical weapons? It’s a series about subterranean history but about how many of us are forever seeking answers to past events in our memories. Eric comes across as a little maddened by his quest, obsessively going every detail of every meeting and every face from his childhood. He pours over documents and at one point has his father’s remains exhumed. Some memories are so painful we can’t ever let go.

One of the miniseries’ most frustrating sections involves legendary journalist Seymour Hersh, who believes he might have found the answers to how Olson died and why, but he can’t write about it because of the danger it might still pose for his source. Of course the villains of this story are more formidable than any Marvel bad guy. Morris selects film clips of powerful men that are quite telling. Former CIA director Richard Helms and another notable CIA director, William Colby, stare and walk with the stride of the patrician masters of dark arts- cold, poised, ruthless. Olson was a mere cog compared to their more infamous ventures including coups in Iran, Chile, Guatemala and the Vietnam War.

Morris has been down this road before, chronicling some of our more pathological political traits. His “Standard Operating Procedure” tells the story of the torture photos from Abu Ghraib, “The Fog of War” is a one on one interview with Vietnam War architect Robert McNamara, and “The Unknown Known” is a sit down with McNamara’s historical heir, Donald Rumsfeld. These are not dry political tomes, like “Wormwood” they are about how history is above all made by individuals with their own quirks and drives.

“Wormwood” is murder mystery and disturbing history lesson. Working with Netflix, Morris has been given proper space to explore this story. It is patient but gripping, as haunting as a family scrapbook containing strange memories.

“Wormwood” premieres Dec. 15 on Netflix.