‘The Death of Stalin’ Triumphantly Mixes Bureaucratic Satire With Political History

Aaron Berke

Political satire on a subject like the death of Joseph Stalin is difficult to pull off. Yet Italian/Scottish filmmaker and “Veep” creator Armando Iannucci accomplishes it with delightfully sardonic fervor. “The Death of Stalin” revolves around the power struggle following the Soviet dictator’s demise from a cerebral hemorrhage. Chaos ensues as Stalin’s inner circle intensely debates their next moves, with treachery swiftly enveloping their ranks. The usual suspects include Moscow party leader Nikita Khrushchev (Steve Buscemi), NKVD head Lavrentiy Beria (Simon Russell Beale), Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov (Michael Palin), and Deputy General Secretary Georgy Malenkov (Jeffrey Tambor). With each member of Stalin’s inner circle forming alliances against one another, the film becomes a wickedly clever mixture of witty farce and mortifying truth.

Iannucci has an uncanny ability to seamlessly insert moments of real drama into otherwise comedic set-pieces. The opening sequence of “The Death of Stalin” features a live Orchestra performing a Mozart concerto for Stalin’s listening pleasure. Unfortunately, no one was recording the performance. This results in a chaotic scramble to get the performers and the audience back together for a repeat performance. The scene is filled with tongue-in-cheek comedy, as the conductor accidentally knocks himself out, necessitating an emergency conductor replacement. But there’s also a palpitating nervousness as the very real risk of Stalin having every member of the Orchestra killed looms over the hall. Iannucci lets the comedic overture flourish while subtly plucking at the strings of dread.

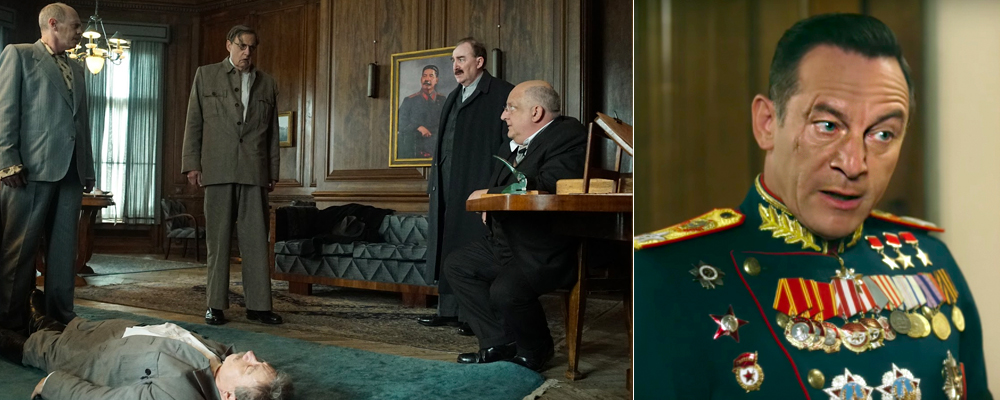

Iannucci excels at fusing political drama with physical comedy. Following Stalin’s brain hemorrhage, the Soviet leaders gather around Stalin’s unconscious body. The sequence features several comedically grand entrances, as Khrushchev, Molotov, Beria and Malenkov enter the room one by one. As more of them enter, the debates over what to do with Stalin frenetically increase, becoming less coherent and more amusing. Indeed, at this point the film begins to feel a bit like a murder mystery-comedy, where the players are trapped in a room with a body, trying desperately to figure out how to get rid of it. But again, Iannucci is juggling historical material. While it’s not always accurate, Iannucci still manages to make the Soviet committee debates about Russia’s future genuinely compelling – debates that occur in conjunction with their desperate attempts to avoid the spreading puddle of Stalin’s urine. Here, as in many other sequences, the comedy is seamlessly fused with politics.

Iannucci’s point appears to be about the fallibility of human beings handling a shift in power. Much of the comedy stems from Malenkov’s, Beria’s, and Khrushchev’s obsessive desire to maintain an aura of absolute power in the public’s eye, despite their complete inability to function as a cohesive unit. Khrushchev and Beria are on opposing sides, and they individually yank de facto leader Malenkov’s ear in their respective direction while secretively plotting against the other. Malenkov, meanwhile, is more interested in looking the part of a respected leader than paying any attention to his squabbling Committee leaders. Malenkov spends the latter portion of the movie fixating on finding the one girl who will help to make his official portrait look innocent and appealing. Malenkov is only interested in appearances, while Beria and Khrushchev are solely fixated on consolidating power while continually bungling their own attempts. Through this destructive push and pull, Iannucci winks at his audience, reminding us of the imminent disaster of a political cabinet enmeshed in chaos.

The characterization of each member of the Soviet committee feels similar at times, but the actors help to distinguish them. Steve Buscemi is a surprising choice to play the future leader of the Soviet Union. But Buscemi’s uniquely disdainful brand of satire lends Khrushchev moments of biting sarcasm as well as lethal brutality. This becomes especially evident in the film’s final act, when Khrushchev implements his famed coup de tat and Buscemi reveals a chilling menace that was lurking just beneath his satirical veneer. Simon Beale is nearly unrecognizable as Beria, and that’s to his credit. Of all the characters, Beria seems to most authentically exist in 1950s Russia. Beale portrays Beria gleefully enjoying his role as Stalin’s highest-ranking officer, gloating about all the horrible acts he committed as the head of the NKVD. On the flipside, Jeffrey Tambor goes full Tambor as Malenkov, playing into his most idiosyncratic acting quirks. Tambor preens and postures in front of the camera, posing for an imaginary portrait even when there’s no camera in front of him. He pompously shows off his slickly glued hair, pasty white skin, and formal suit that’s two sizes too big for him. This paints a picture of Malenkov as a goofy man so consumed in his image that he forgot to look in the mirror.

The blend of satire and drama reaches a fever pitch by the film’s third act, when the Soviet committee holds Stalin’s wake in the Hall of Columns. Inside the hall, the atmosphere is quiet and comedic, as the four leaders angrily debate amongst each other about who let in the Bishops. Malenkov, Molotov, Beria and Khrushchev loudly hiss at each other while attempting to maintain the veneer of regality. Meanwhile, Khrushchev has secretly enacted a plot to allow the mourning Russian public into Moscow. This results in the NKVD guards opening fire and killing 1,500 people. Mass bloodshed occurs in the same sequence as the four committee leaders’ petty squabbling, and neither takes away from the other. Instead, Iannucci makes a convincing argument that self-centered political trickery and unfiltered mass slaughter have a clear correlation.

“The Death of Stalin” succeeds as both hilarious government satire and horrifying political reality. Iannucci shapes the film around an event 64 years in the past, and uses it create striking parallels to political upheaval in today’s world. The film is both timely and timeless, utilizing two totally different genres and fusing them into a unique depiction of humanity’s outrageous self-interest. With “The Death of Stalin,” Iannucci proves that self-interest can be hilarious and terrifying at the same time.

“The Death of Stalin” opens March 9 in select cities.